Gorbachev, Lenin, Stalin and Putin went beyond imagining the godless world John Lennon sang about — they built it.

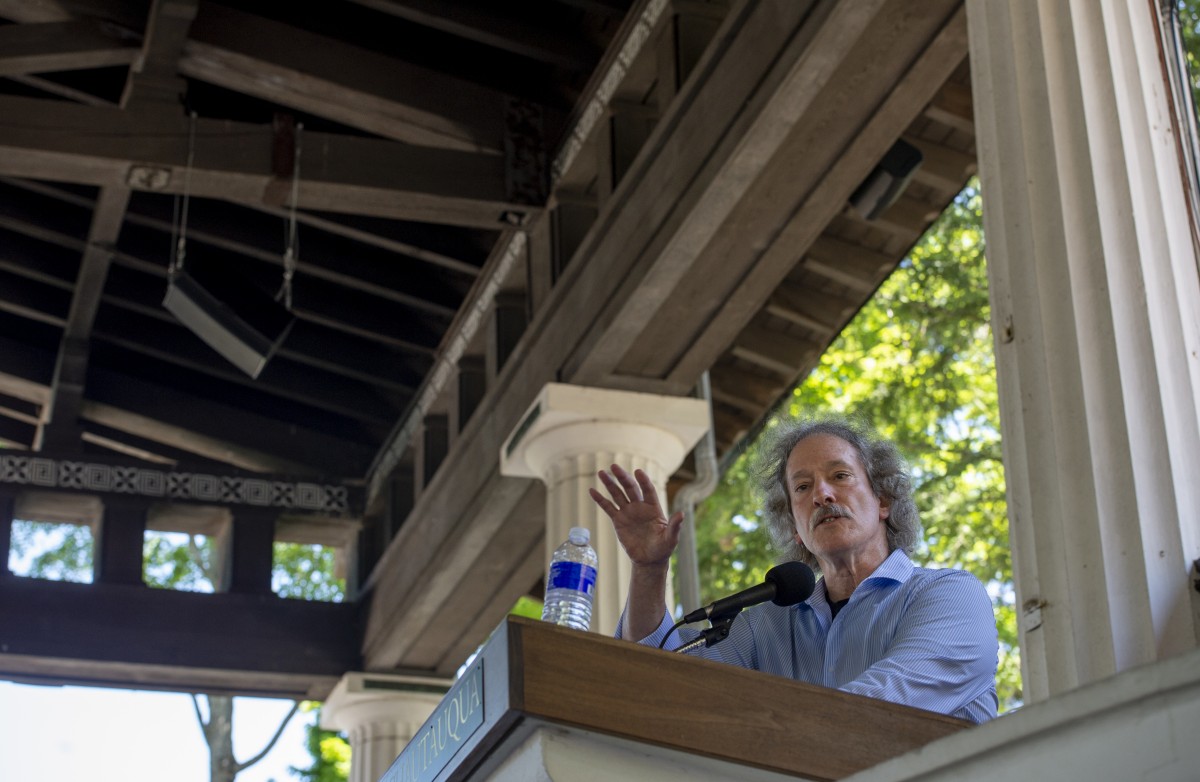

At 2 p.m. Thursday, July 19, in the Hall of Philosophy, Ori Z. Soltes, a professor at Georgetown University, former director and curator of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum and lifelong scholar, discussed how Russia’s most memorable leaders of the past 75 years have shaped religion in his lecture, “The New and Old Russia: Between Millennia: Religion from Gorbachev to Putin,” as the last of Week Four’s interfaith theme, “Russia and Its Soul.”

Soltes was in Kiev when the Russian government officially returned control of the Kiev Pechersk Lavra monastery to the Russian Orthodox Church in 1988.

“This was a very important moment and obviously symbolized the (need) to reopen the open acknowledgment of the importance (of Russia’s religion),” Soltes said.

As conversations about religion made a transition, so did government leadership. Three years after Soltes’ trip, Boris Yeltsin replaced Mikhail Gorbachev and became president in Russia’s first direct election.

Throughout the 1990s, Chechnya, a predominantly Muslim-occupied Russian republic in the North Caucasus, was a tipping point in Moscow conflicts.

“The Chechens were feeling pressed upon by the Russians, and the Russians were feeling pressed upon by the Chechens,” Soltes said.

In 1999, Russia went to war after Shamil Basayev, a Chechen Islamist and rival of secular leadership, led an invasion of Dagestan. Vladimir Putin took the lead in ending the spread of the insurgency to neighboring republics by starting a campaign to defeat the rebels.

That same year, Boris Yeltsin resigned as president, and Putin won the following election.

“(Putin) won rather quick popularity for suppressing the Chechen insurgency, although erratic violence continued for sometime thereafter,” Soltes said.

To contextualize this time period, Soltes quoted a 1993 article from The New York Times titled “Religion Returns to Russia, with a Vengeance.”

“While tradition put the Orthodox at an advantage, the established Church’s long coexistence with the Soviet state left it tainted,” he read. “All priests were carefully screened by the state, and many bishops and priests are still hounded by accusations of collaborating with the K.G.B.”

Soltes went on to explain how the article said even though the Russian Orthodox Church finally won freedom from state control, it still finds itself “bowed under the baggage of its past” in present day.

Soltes also referenced a section in the Times’ article about an event at the Lokomotiv Stadium in Moscow. In 1993, more than 20,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses gathered and stood and applauded for more than an hour as 2,000 neophytes took turns being baptized. In 2017, Putin classified Jehovah’s Witnesses as an “extremist organization.”

“Clearly, that must have been in response to what this article said back in 1993,” Soltes said. “The Church is running to the state to protect us from the invasion of all of these improper, incorrect, inaccurate Christian denominations and the like.”

Soltes believes Putin’s decision to outlaw Jehovah’s Witnesses makes it clear that throughout human history, “religion has never, ever, ever been disconnected from politics.”

“The Pharaoh rules because you believe if you are part of his constituency that he is at least ruling with the dignity of the gods, or at most, the god itself incarnated,” Soltes said. “Whether it is the Pharaoh, those desperate monarchs or whether it is the occasional American presidential candidate, religion and politics have always been interwoven.”

Soltes saw the intersection of religion and politics in the streets of Kiev in 1988 during a Pamyat rally. Pamyat is is an anti-Semitic organization that identifies itself as the “People’s National- patriotic Orthodox Christian movement,” Soltes said.

“I do not mean that the Church has associated itself with right-wing nationalism,” Soltes said. “I think that more often than not, the right-wing Russian nationalists associate themselves with the Church, (believing that) to be Russian is to be Russian Orthodox, and that’s how you have to be. There are not two ways about it.”

Soltes believes the “politics over religion” mentality is why some people might long for the return of the Soviet Union.

“We want to be dominant; we want not to be respected as much as feared,” he said. “And that is one of the things the young people who were mentioned this morning (at the 10:45 a.m. lecture) like about Putin — that he has made (Russia) feared again. A disturbing thought, at least in my mind.”

Soltes compared Putin to a leader of a cult, and said that there is something mystical to him about political figures who are seen in the public eye as someone “larger than life.”

“By mystical, I mean they’re perceived to have some more of a connection to something beyond them, and I think Putin has captured some of the imagination of his population with respect to that,” he said.

However, Soltes said, mysticism and masculinity go hand in hand for Putin because he is admired for “his macho as well.”

The same fear was directed toward Joseph Stalin. Soltes said even though Stalin murdered 30 million of his own people, he is still rising in popularity in present day as a symbol of another era when Russians were feared.

Soltes believes, in terms of fear, there is both a conscious and unconscious association between Putin and Stalin. And the comparisons do not end there. Although the two figures do not share the same name, Putin does share the same title “apropos of Jesus,” just like Vladimir Sviatoslavich, who brought Christianity to the Kievan Rus’, and Lenin, who created the Soviet Union.

“What a convenience,” Soltes said. “We’ve got the three Vlads, another trinity.”

Another similarity among these Russian leaders is the shifting support of religion.

Construction and restoration of Orthodox churches started in the 1990s and has continued under Putin’s leadership, as has the teaching of religion in schools. In January, Putin announced his initiative to incorporate Islam’s beliefs and language in Russian schools’ curriculums. However, in July, he approved a package of anti-terrorism laws that sent the opposite message. These laws forbid sharing faith in homes, online or anywhere other than recognized church buildings.

To Soltes, a symbol of these leaders’ fluctuating religious viewpoints is St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg. The cathedral was built under Nicholas I, completed under Alexander II and was designed to make a statement that St. Petersburg was the real capital of Russia, not Moscow.

It operated as a church until 1931, the same year Stalin blew up the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Although Stalin did not blow up St. Isaac’s, he did convert it into a museum of religious history. However, at the end of the Soviet period, it was decided that the cathedral needed to be reverted back to an active church. It took until 2017 for the cathedral to be revived, and while there is currently an active chapel inside, part of the building still functions a museum.

“Of course, you pay to go in the museum,” Soltes said. “So, we are not stupid, are we? It is a source of income; why would we give that up just for faith?”

Soltes finished his lecture by reading a poem by Joseph Brodsky, a 20th-century poet who shifted from writing poetry in Russian to writing in English. The poem, “Elegy,” depicts the battle of spirituality in the heart and soul, Soltes said.

“ … now the place is abuzz with trading / in your ankles remnants, bronzes / of sunburnt breastplates, dying laughter, bruises, / rumors of fresh reserves, memories of high treason, / laundered banners with imprints of the many / who since have risen,” Soltes read. “At sunrise, when nobody stares at one’s face, I often, set out on foot to a monument cast in molten / lengthy bad dreams. And it says on the plinth ‘commander in chief.’ / But it reads ‘in grief,’ or ‘in brief,’ / or ‘in going under.’ ”