A home is nothing without a solid foundation. Hemlock trees, one of the oldest and third-most populous tree species in New York, provide just that for countless insects, plants and wildlife. In recent years, a new menace has crept its way up the eastern coast to put this foundation species at serious risk.

An invasive insect species, hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) arrived in New York in the early 1980s, presumably from infested nursery stock, according to New York State Hemlock Initiative. Originally from southern Japan, HWA has already decimated large regions of hemlocks in the southeastern part of the country near North Carolina and Tennessee.

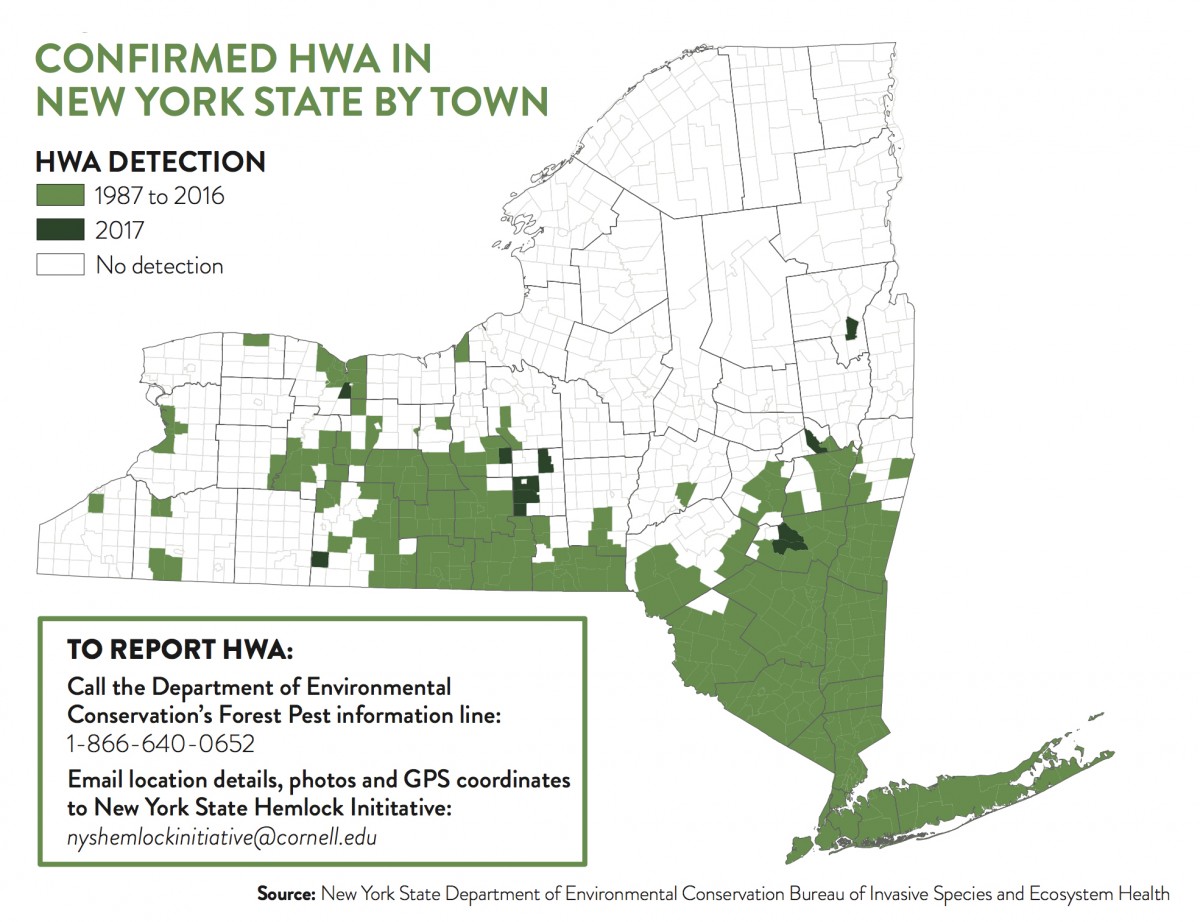

Primarily found in eastern regions of the state, HWA feeds on the nutrients of the hemlock tree, leaving a weakened tree crown and pale, off-color needles before eventually killing the tree if left untouched. With a lack of predators in this part of the country to keep them in check, HWA can cause catastrophic damage to this important player in the ecological system.

Cornell forest entomologist Mark Whitmore has been studying adelgids off and on for over 40 years. For the past 15 years, he has worked out of a lab at Cornell University, studying the expansion and biology of the species as it adapts moving north.

“We don’t really know a lot of the biology of how they adapt,” Whitmore said. “Suffice it to say, they will eventually adapt to cover the entire range of hemlocks of North America.”

Whitmore said it is important to approach HWA from a worst-case scenario perspective, and just be relieved if everyone is wrong. He said it’s been sad for him watching HWA rip through the south, changing the Great Smoky Mountains National Park forever.

“I think it’s important to realize the place of hemlocks in the forest,” Whitmore said. “We call it a foundation species because it forms basically the foundation a myriad of species depend upon for their existence.”

In contrast to the emerald ash borer (EAB), an invasive beetle species that has destroyed hundreds of millions of ash trees across the continent, HWA is seen as a much slower moving invasive, Whitmore said. Whitmore emphasized that this doesn’t mean HWA is slow moving — only in comparison.

“Once HWA gets into a place, it will start spreading rapidly,” Whitmore said. “(HWA) doesn’t kill trees as rapidly as EAB, but that shouldn’t keep us from moving as quickly as possible. This thing is a ticking time bomb, and we’re lucky to have a little bit of time.”

Whitmore said he and his staff work alongside state, federal and Canadian agencies, with biological control of HWA not recognizing formal boundaries. Biological control involves using natural predators, insects or pathogens to manage pest populations; in the case of HWA, two main predators from the Pacific Northwest have been studied, with one, the Laricobius nigrinus beetle, having been introduced in 16 states successfully since 2003.

With the HWA not killing trees as quickly as other invasives, Whitmore said there is the opportunity to use systemic strategies and resources to manage the spread.

“No. 1, we shouldn’t be complacent,” Whitmore said. “The most important thing for people to realize is that hemlocks are a resource we have to pay attention to. It’s all too often the case that you don’t know what you have until it’s gone.”

An important tool in HWA management is surveying and reporting from the general public, Whitmore said. With resources like iMapInvasives, a state-sponsored online invasive species database and mapping tool, scientists and the general populous can actively map and alert officials of HWA in their area.

“Getting the extra eyeballs is critical to multiplying the efforts and giving us the best advantage to use our resources,” Whitmore said.

Elyse Henshaw, a conservation technician for the Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History, has partnered with Jamestown Community College and the Chautauqua Watershed Conservancy in recent years surveying the land in winter months. Primarily dealing with survey services, Henshaw said researchers avoid working during these summer months because of the high activity of HWA. During this time of year, HWA can easily be moved by people from one area to another.

Henshaw, alongside volunteers and others in the field, check and survey areas with heavy concentrations of hemlocks. The surveyors look for the white, waxy wool masses found on the bottoms of hemlock twigs produced by females while developing in winter months.

“There is a cost benefit to surveillance,” Henshaw said. “Working closely with (New York Department of Environmental Conservation), if people say they do find it, we can connect them with DEC who can help out and give them the next step for what to do.”

Despite being ahead of the curve, Henshaw said there is still an effort to distribute information and prepare people for the adelgids arrival.

“If it gets in and is allowed to have its way, it will destroy a lot of trees,” Henshaw said.

Andrea Locke is coordinator for Western New York Partnerships for Regional Invasive Species Management, or PRISM, a partnership created to bring together like-minded stakeholders to affect change on a larger scale. Main functions throughout the eight PRISM regions in the state are education, research and land management, Locke said.

“Traditionally, these issues have been handled on a site-by-site basis,” Locke said. “When you’re managing on a site-by-site basis, you’re really not addressing, in the long run, the influx of these species.”

Through outreach and planning next steps, Locke said she works to ensure information is as accurate and up to date as possible. While HWA’s presence in this part of the state is still low, there have been cases seen, including infestations in Letchworth State Park, Allegheny State Park and Zoar Valley.

The 2014 infestation in Zoar Valley was treated with two separate pesticides, one short term, one long term, which seems to have successfully kept the HWA at bay since, Locke said. Although the chemicals are applied either by injection, or soaked into the roots with limited pollinator impact, Locke said there are still concerns. Cost is one because of the need for reapplication every few years.

“If you’re in the span of 100 hemlock trees, but only one or two have HWA, you can treat a few hundred trees ahead of infestation and get good protection,” Locke said. “With EAB, by the time people see it, often the trees are already dead. If you see them even a few miles away, it’s still almost too late.”

Betsy Burgeson, supervisor of gardens and landscapes at Chautauqua Institution, had been involved in dealing with HWA while at SUNY Fredonia before she started working on the grounds in 2015. Once she started working at the Institution in early 2016, HWA was something Burgeson said she was really worried about because of people traveling and bringing firewood from other areas.

“I did trainings with my crew the first year,” Burgeson said. “In October (and) November, I had them go out and survey the hemlocks, map out where they are.”

Almost 500 hemlocks are inventoried on the grounds, but Burgeson said the total number is probably double that since the ravine has not been inventoried.

“That’s the first place we’ve been looking because (HWA) tend to be found on low trees near water,” Burgeson said. “It’s a main tree along the line of our ravine. They cool the water. They hold the soil in place. If we lose those trees, everything is under attack.”

With the trees providing the foundation for so many of the plant and animal life at Chautauqua, Burgeson and her crew take HWA and other invasive species and diseases seriously. Oak wilt disease, a threat to the red oaks on the grounds, is a lethal fungus that is spread by insects and kills its host quickly. If the disease is found in an area, the DEC cuts down every tree to limit the spread of the disease.

“Seven of our 10 largest trees are red oaks,” Burgeson said. “The bad part of this disease (is) if any oaks have roots crossing, the fungus can spread this way as well.”

As with EAB and oak wilt disease, Burgeson said she wants homeowners and visitors to be informed about how to recognize HWA and its symptoms. Burgeson said she would rather receive 100 false calls than no calls at all if the infestation could have been been prevented at an earlier time.

“(If there are) any worries about trees, make sure that we’re aware of it,” Burgeson said. “(Loss of hemlocks) allows these other invasive species to come out and take over. It’s one big ecological nightmare if one thing gets out of whack and what can happen as a result.”