Definition of lace from Merriam- Webster: An openwork usually figured fabric made of thread or yarn and used for trimmings, household coverings and entire garments.

Lace is a product that invokes associations to many different concepts or objects, including Victorian clothing and interior design, labor-intensive toil, pattern, decoration, opulence, history, skill and fine craft. Lace dates back to at least the mid-15th century; it has been revered ever since, by the clergy, the aristocracy and royalty including Queen Victoria, who was married in a lace gown. “Ties that Bind” is an exhibition curated by fiber artist and Assistant Director of Galleries Erika Diamond. The impetus to design an exhibition around the theme of lace is not unexpected, as Diamond’s own fiber works draws heavily on the history of Western tapestries; both lace and tapestry are timeless and enduring textile processes.

“Ties that Bind” brings together eight artists whose work evokes lace in some way. New York-based Sui Park, who has a background in both fiber arts and interior architecture, has crafted intricate structures from the most modest of materials. “Mostly Cloudy” is a series of hanging, three-dimensional oval shapes that are reminiscent of both clouds and amoebas. From a distance, they look as though they may be formed from glass or resin, but closer inspection reveals that they are made from thousands of zip ties, linked together in loops to create three-dimensional forms. The object themselves are stunning, but just as intriguing are the shadows they create on the wall behind them. Also by Park are seven organic forms displayed on gray pedestals that are each no more than 12 inches in height or width. Again, from a distance it is not obvious what material was used in their creation: Up close, it is evident that they are made from countless layers of woven fishing line. These magnificent objects transcend the cheap, mass-produced materials from which they are made. The relationship to lace is especially apparent in the actual crafting of Park’s works. The time-consuming and repetitive task of making bobbin lace is comparable to the tedious chore of linking thousands of zip ties or weaving objects from fishing line.

A familiar characteristic of lace is the open structure of the pattern and the reliance on negative space as part of the design. Two artists whose work is made from cut paper similarly use negative space as a motif. Working from two-dimensional sketches, Eric Standley laser-cuts sheets of colored paper, then stacks them hundreds thick to create layered designs viewed through a square or round shape cut into matt board. It is as if we are seeing the interior of the artwork. The forms are simultaneously beautiful and off-putting, as they share similarities to stained glass or sinew, DNA strands or patterns on brocade or lace.

Richmond-based Leigh Suggs’ more minimal paper- cut works are subtle yet powerful. “Drift II” is a paper piece that is 58 by 58 inches. Hand-cut in the paper are thousands of tiny squares and rectangles which from a structured grid that is interrupted only with a swoosh of lines cutting diagonally through it. Approaching the piece the viewer sees through the cut-outs a red, nebulous space that seems to vibrate, alluding our ability to clearly focus on it. Patient contemplation of the work reveals that the back of the paper is colored an intense red. This color is being reflected on the wall behind and seen through the tiny squares.

On display by Crystal Latimer are two larger predominately red, black and rose-colored paintings with layers of shapes that are floral and in places, repeated much like patterns on lace. Also on view are her eight square acrylic-on-paper works. In each of these, a translucent, intensely colored acrylic brush stroke aggressively marks the surface. Again, there is an element of surprise when the works are more closely inspected: on top of the paint are faint lace-like patterns in light metallic linework inspired by the styles of decoration found on ceramics or textiles in Costa Rica, a country which is part of Latimer’s heritage.

Philadelphia-based Rebecca Rutstein utilizes repeated, open-structured patterns that link nicely to other works in the show. She works from sonar maps and other oceanic data, inspired by fractal patterns and the mysterious underwater world. In “Connection and Degradation IV,” a black background becomes the base for a lattice of interconnected honeycomb shapes meticulously painted on with gray and white paint. As well as the paintings, a powder-coated steel cloud shape is on display. Laser cut into the steel are hundreds of small squares and rectangles, again, suggesting the negative space in lace patterns. This piece is similar to the forms installed on a building at Temple University in “Sky Terrain” (2015), a spectacular, LED-lit permanent outdoor public art commission by Rutstein.

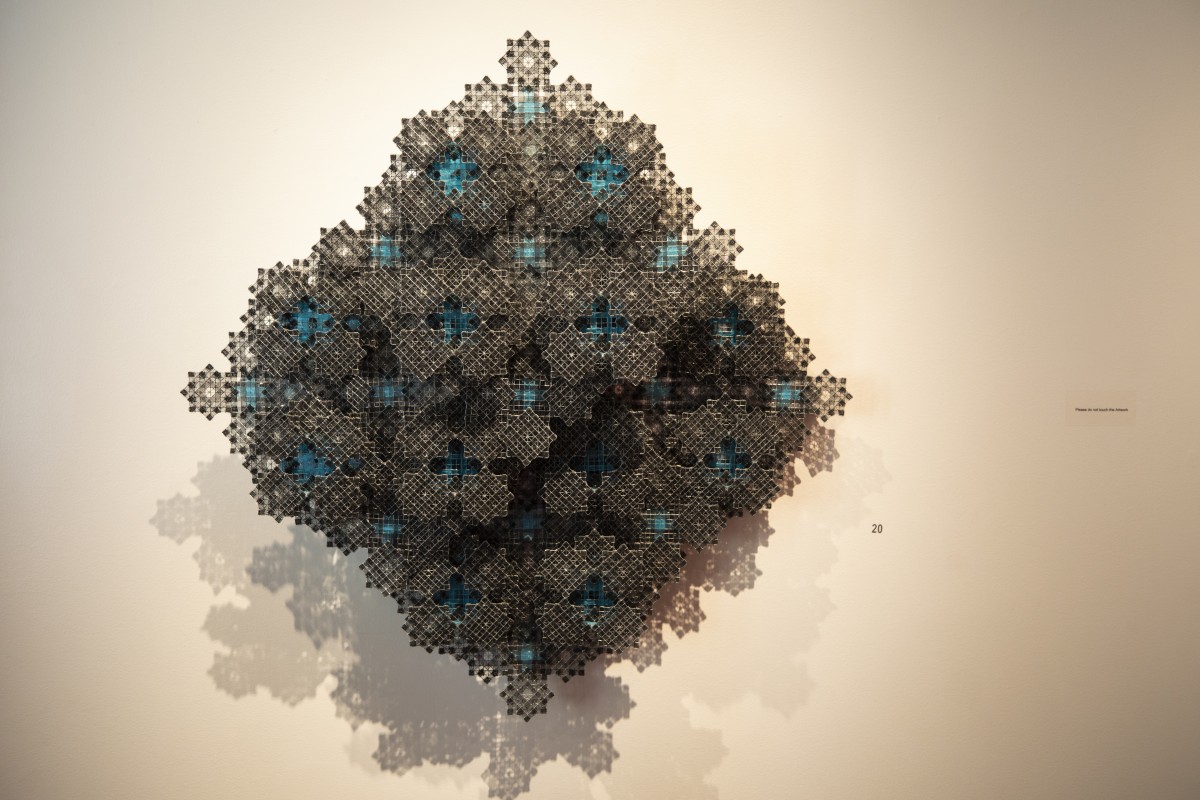

Jonathan Capps’ stunning hand-blown large glass bowls in colors ranging from intense blues, yellows and reds to subtle turquoise and corals are masterfully crafted. A motif through the works is the lattice pattern created within the glass, which follows the contours of the forms. Katie Shaw, influenced by textile design, scientific diagrams and architectural structures exhibits a series of predominantly blue inkjet prints that have surfaces that look like heavily layered ballpoint pen. Traditional patterns such as mandalas, grids and trellises dominate. Another pattern Shaw uses is chain link, making an ironic connection to the fact that chain link fence and bobbin lace are both made using only two simple movements, the cross and the twist. Shaw’s three-dimensional wall piece on display, “Cleft,” is crafted from squares of metal grid; window screening has been cut into strips and woven through the grid. It looks somewhat like a monumentalized stack of electronics jutting off the wall, but, almost unbelievably, the shadow the object casts onto the wall behind it looks exactly like crocheted lace fabric edging.

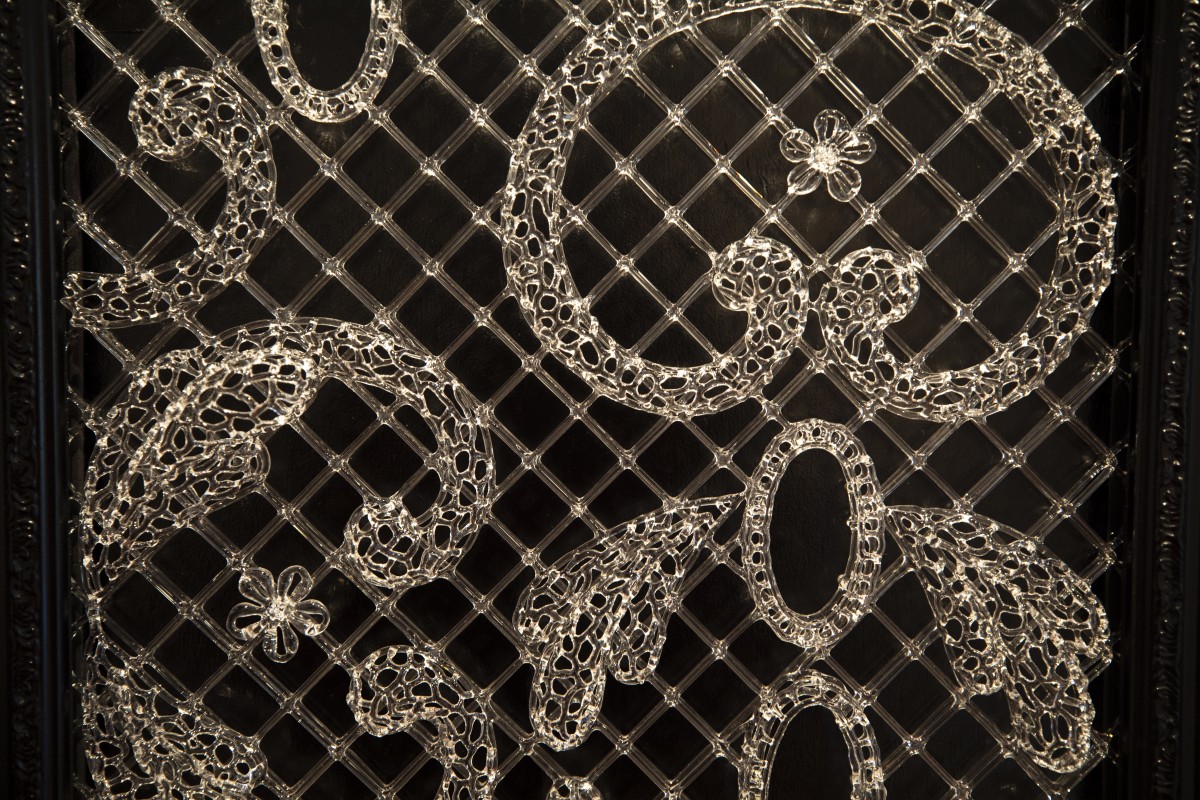

But, it is the work of Lisa Demagall that brings the show together. The delicate flameworked borosilicate glass pieces are replicas of traditional heirloom lace patterns like Chantilly or point d’esprit. The majority of the pieces are around a few feet in height, oval or square and in wooden frames that give them an antique look. “Doily Bowl, Black” is slightly different as the glass is formed into an open lattice dish that is hung on the wall. The choice by the curator to paint the walls red was clever, as the clear glass is enhanced by this backdrop.

The connections between the works and their relationships to the aesthetics and craft of lacemaking are clear. Yet Diamond, in her curatorial statement, encourages us to contemplate lace as a metaphor for our entanglements, our attachments to time and place, and our connections to each other.

Pittsburgh-based Melissa Kuntz is professor in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at Clarion University of Pennsylvania. She holds an MFA and MA from SUNY Purchase. She has been writing art reviews since 2002 for publications such as the Pittsburgh City Paper, Canadian Art magazine, The Chautauquan Daily and Art in America magazine.