Review by Howard Halle

As such exhibitions sometimes do, “Masters In Craft,” Strohl Art Center’s energetic offering of nine artists working in jewelry-making, metal-work, ceramics, glassblowing, fabric and fiber, raises the question, “What separates craft from art?” I suspect the participants in the show — Tina Williams Brewer, Christian Burchard, Kat Cole, Jim Connell, Ed Eberle, Sergei Isupov, Anne Lemanski, Lyla Nelson and Stacey Lee Webber — would answer, “nothing,” and indeed, their contributions are refined and beautiful, indistinguishable from art except for the fact that they’re presented as utilitarian, decorative or both. So why bring up the issue at all? Blame history.

Prior to the Renaissance, there wasn’t the hierarchical distinction between art and craft that we make today. Craft was how you made stuff, though, of course, quality varied by class. If you needed a cup, say, you made it by hand, but if you were wealthy enough, you’d pay a goldsmith to fashion you a chalice worthy of Croesus.

Still, even mediums like painting served a practical purpose. Church frescoes and altarpieces, for instance, taught the stories of the Bible to illiterate congregants. And, if you ever visit the Egyptian wing of New York’s Metropolitan Museum, you’ll find another example in a group of uncannily realistic, Roman-era portraits that represent, for my money, some of the finest examples of the genre. Yet, they are, in fact, funerary masks meant to identify the mummified remains of the subjects as they make their journey through the afterlife.

However, with the emergence of Leonardo, Michelangelo and other giants of 15th- and 16th-century art, a gap opened between the perceived roles of fine artist and artisan: Artists created primarily as a means of self-expression, while artisans tied their labor to utility. Two centuries later, the Industrial Revolution furthered the divide by supplanting things made by hand with manufactured goods.

More pertinently for the artists in this show, the period also ushered in a new appreciation for craft and the handmade — one that was, in fact, ideological in nature. Aesthetes such as John Ruskin and William Morris critiqued the spread of industry and its deleterious impact on mankind. They imagined returning to a prelapsarian society of woodcarvers, potters, metalsmiths, glassblowers and weavers whose authentically fashioned objects contrasted sharply with the soulless commodities rolling out of factories.

This thinking gave birth to the Arts and Crafts movement, which gained popularity in Europe and North America between the 1880s and the 1920s. Not surprisingly, this aesthetic suffered its own backlash with the rise of Modernism, which prized clean lines over ornamentation in a rationalist approach to architecture and design that comported well with post-war corporate capitalism and its emphasis on consumerism.

But that, too, eventually led to yet another revival as the 1960s counterculture, with its whole-Earth, back- to-the-land ethos, helped to spark the studio craft movement. Figures associated with the practice — particularly West Coast ceramicists such as Robert Arneson, Ken Price and Peter Voulkos — pushed craft into pure aesthetics with works that resembled pottery, jewelry, glassware, et cetera, but existed mainly to be collected and displayed.

This was nothing new, exactly (after all, what other purpose does a Hummel figurine serve except display?), but the movement’s artistic ambitions and self-conscious questioning of the line dividing “art” from “craft” were a break with tradition. That legacy remains visible in this show.

The artists of “Masters In Craft” pursue their creations along a continuum ranging from functional (albeit in a vestigial sense) to completely sculptural, ultimately making it hard to distinguish between the two. This seems especially evident in the objects that echo vessels of varying sorts.

For example, Burchard, a native of Hamburg, Germany, based in Oregon, offers a pair of pieces resembling rounded gourds. Bleached into a boney, off-white pallor, they’re made from the roots of madrone trees, an evergreen native to the Pacific Northwest. Buchard creates his pieces by turning them on a lathe, often using green wood that warps unpredictably to impart an element of chance. That may account for the irregular contours of his work here, though it’s not clear whether they were made in this fashion. Nonetheless, they posses an enigmatic, anatomical quality thanks to their hard, skull-like shape and nish.

The human form is evoked a bit more explicitly in a hand-blown glass vase by Nelson, which is pinched in the middle like a waist to suggest female breasts and hips. Another feminine marker, perhaps, is the bright red hibiscus flower, and deep green tangle of stalks and leaves, entwined around the piece. These have been sandblasted to stand out in deep relief from a milky background. Nelson was born and raised in Puerto Rico, and it’s easy to imagine that memories of that balmy island inform her choice of decoration.

A piece by Connell, who teaches ceramics in South Carolina, likewise employs sandblasting to enliven his work with an iridescent sheen. Ribbed and torqued with scalloped, batwing-like edges, his object resemble a sort of squat chrysalis. Though you might imagine otherwise, given Connell’s taste for complex form, his works are generally wheel-thrown.

Eberle, who lives in Homestead, Pennsylvania, takes a narrative approach in his porcelain objects, which are at once postmodern and classical. The selections here include a pot shaped like a man’s head and a large, cylindrical vessel that flares at the top. The exterior is covered with naked bodies, animals and cryptic inscriptions, rendered with pen-and-ink precision in black and white, though Eberle’s style leans toward figurative expressionism. While his meaning is elusive, his efforts could be taken as a meditation on the human condition.

The figure plays an equally important role for Isupov, an Estonian émigré, who offers surreal sculptures in glazed porcelain. Laden with private symbolism, his work features images of men and women interacting in scenarios fraught with erotic tension — both as surface embellishments and as three-dimensional forms morphing into chimerical combinations of human and animal.

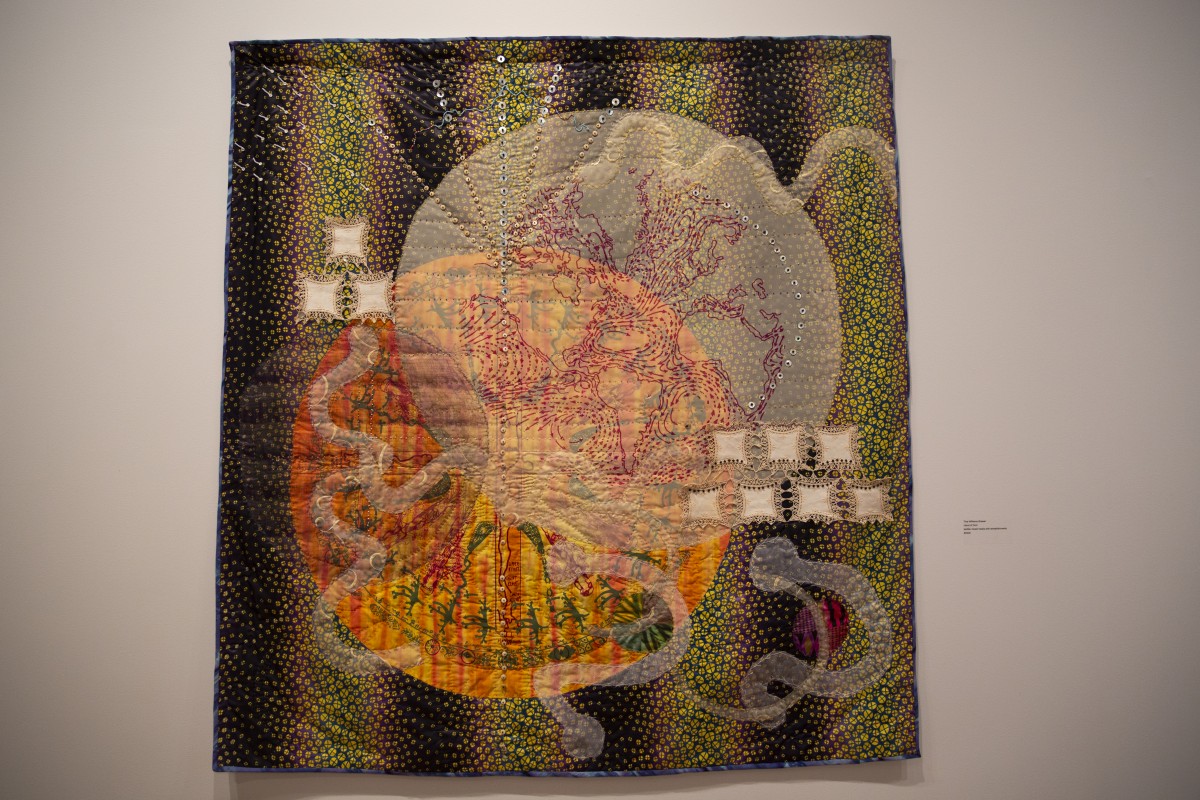

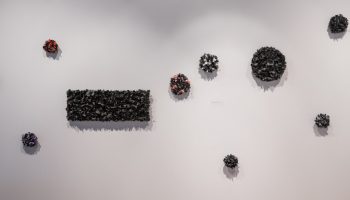

Other mediums associated with craft are included here, of course. Fiber art is ably represented by Brewer, a West Virginian whose story quilts delve into African-American history with a colorful inventory of fabrics that sometimes include photo-transfers. Whimsical woodland creatures by Lemanski, who lives and works in the Blue Ridge Mountain region of North Carolina, appear to be made of stuffed fabric from a distance, but a closer look reveals that they are painstakingly fabricated by hand-stitching paper printed with bright patterns onto an armature of copper rods.

Philadelphia jewelry-maker Webber also employs copper at times — in the form of pennies. Lincoln’s portrait in profile from the coin (along with other presidents and potentates adorning specimens of pocket change from around the world) is sawed out and used in pins, cufflinks and other accessories. Dallas-based Cole, meanwhile, uses steel, brass and enamel to fashion work like the abstract wall relief here etched with the image of an oil derrick.

Titled “Drilling Down,” Cole’s piece may be a metaphor for the way artists are compelled to dig at some version the truth. And if there’s anything linking the works in “Masters In Craft,” it’s that their creators remain true to their materials — and to their visions, however you care to frame them.

Howard Halle is editor-at-large and chief art critic for Time Out New York.