The collaboration between As One’s creators began like all great partnerships: drinking rosè at home over dinner.

It was at that dinner in composer and creator Laura Kaminsky’s home where librettists Mark Campbell and Kimberly Reed met, solidifying the team that would construct an opera about a transgender woman.

As One premiered in September 2014. Steven Osgood, general and artistic director of Chautauqua Opera Company, conducted the production and has wanted to bring the opera here since the premiere. That is being realized after 21 other productions of the opera, and As One will be staged at 4 p.m. Tuesday, Aug. 7, in Norton Hall.

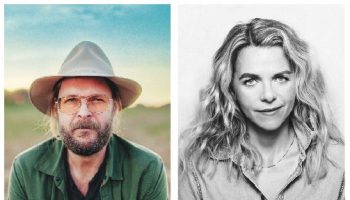

Kaminsky, Campbell and Reed will all be in attendance. The original cast, consisting of Kelly Markgraf and Sasha Cooke, will portray Hannah Before and Hannah After, respectively. The Fry Street Quartet, which performed the score during the premiere, will provide the music. Chautauqua Opera’s production will unite the original musical team for the first time since 2014.

Since the premiere, As One has become the most-produced contemporary American opera in North America, with Chautauqua being the 22nd production in four years. The journey from that first bottle of rosè to today’s performance has left an impact on the audiences that have seen it and those directly involved with its production.

The reach of As One

Stage Director Matt Gray, who conducted As One in Berlin, will join the original team for the Chautauqua Opera performance. Gray is the producing director of American Opera Projects, the company that originally produced As One.

Kaminsky liked Gray’s direction in Berlin, and it was important to her that someone close to the production’s origins direct this specific performance.

“There was a lot of subtle and interesting physical staging (about Gray’s production) that we thought was evocative and sensitive,” Kaminsky said. “I think that he uses set pieces and props in a useful and meaningful way, not just to clutter up a stage or generalistically.”

Since the opening production in Brooklyn, As One has been performed in Anchorage, Alaska, Berlin, Seattle and 16 other places around the world. At least one person from the original team has gone to each of the performances, except the one in Anchorage.

“So many companies have produced this opera because they say it’s important, and it speaks to (their) audience,” Osgood said. “It’s unbelievable. You can’t allow yourself to expect that on the day of the premiere. You can only look back on that and say, ‘Wow, that worked.’ ”

Before performing in As One, Cooke said she and Markgraf didn’t have a total understanding of what it meant to be transgender. But As One has led to self-realizations, Cooke said.

“I suddenly realized how much I struggle with masculine and feminine divisions. I myself, for various reasons, have not identified with women, and in other ways I do,” Cooke said. “But there are things about the sort of social standards of being a woman that I alway thought, ‘I don’t want to do that. That doesn’t feel like me’ And I think it’s hard to accept myself because the majority (of women) want to do that.”

When As One goes to a “red state,” Campbell makes it a point to go and sit on a panel. If Reed cannot make it, Campbell ensures the production team puts someone who is transgender on the panel.

“What I love about the success of this opera is that I hope that it’s changing people’s hearts and helping make them understand that transgender people should not be denied their rights,” Campbell said.

As One’s origin story

Kaminsky rarely composed vocal music, and she had never written an opera, but the music she did create revolved around activism. Kaminsky and her wife were following the legalization of marriage equality from state to state when she first decided to create an opera.

At 6 a.m., Kaminsky was drinking a cup of coffee while reading The New York Times. She happened across an article about a New Jersey couple that had been married for 18 years, and one was transitioning. The couple decided to stay together because their “souls connected,” Kaminsky said, but if marriage equality was not recognized in their state, their marriage wouldn’t be, either.

“I remember it just flooded me. This is the stuff of opera,” Kaminsky said. “It asks the questions ‘Who am I?’ ‘Who am I in relationship to my people and the world in which I live?’ and ‘Who am I to the societal and political structures in which I live? What do I need to give up in order to be who I am?’ and ‘What do I gain in that journey?’ It just seemed operatic to me, and I knew I wanted to write this opera.”

After reading that article, Kaminsky knew she wanted to craft an opera about a transgender person. She didn’t have a concrete idea, but the quest to find the story began.

In fact, she had the musicians and the performers picked out before the story.

Kaminsky had worked with Fry Street Quartet and knew she wanted the group to be a part of the opera. Then she met husband and wife Markgraf and Cooke, a baritone and mezzo-soprano, respectively. Kaminsky fell in love with the couple after hearing them perform together.

“I was standing in the wings listening to them, and I went, ‘Oh my god, I want them to be in my opera. In fact, I want them to be my opera,’ ” Kaminsky said. “I realized, at that point, I didn’t want any other characters, I didn’t want subplots. I wanted this to be the story of one person on their personal quest to find and become fully realized and find happiness.”

It wasn’t until a date night with her wife that Kaminsky found the inspiration for her story. Her wife had been giving her books to read and films to watch, and that’s when Kaminsky saw Reed’s “Prodigal Sons” for the first time.

The film was about Reed and her journey back to her hometown in Montana as a transgender woman and her quest to reconcile with her estranged, adopted brother.

At that moment, Kaminsky knew she had to work with Reed and incorporate film into the opera.

Kaminsky still didn’t have a story, though, so she reached out to Campbell, a well-known contemporary librettist. She was hoping Campbell would refer her an affordable person to work with, but Campbell decided he wanted to write the libretto as a passion project.

That led to the dinner in March 2013 where Campbell met Reed for the first time, and the group came together.

Crafting the libretto and supplying the music

On the first night he met Reed, Campbell asked her to recall some of her earliest experiences as a transgender woman. Reed told Campbell she had a paper route, and one day she decided to wear a blouse under her jacket. She got up early so no one would see her.

Campbell turned to Kaminsky and said: “OK, this is what a writer dreams of. This is the kind of stories that can be turned into lyrics.”

Reed’s experiences became the basis for the opera’s text. Initially, Reed thought she was just going to produce a film that would act as the setting for the opera, but Campbell thought it would be best to invite her into the writing process.

“I’m cisgender,” Campbell said. “I needed a voice of authenticity to help me create this story.”

Writing her first libretto was fun, especially because she was learning from the best, Reed said.

Though her background was in film, she “felt at home” writing the opera.

“Most of the time, I think that people are assuming that there’s going to be a lot of differences from the filmmaking process, and for me, I’m just always struck by the similarities,” Reed said. “Writing a libretto is not hugely dissimilar from writing a screenplay.”

Campbell and Reed took Kaminsky’s idea of two people playing one person and created Hannah Before and Hannah After. Through those two voices becoming as one, the librettists wanted to explore different themes through song cycle.

For Markgraf and Cooke, being married has helped them portray this one character with two voices. They are comfortable and trust each other, and there is no awkwardness in proximity.

When they first got the libretto, Cooke and Markgraf read it in bed and wept, Cooke said.

“Mark’s words and Kim’s words, they’ve crafted something that is able to speak to all people,” Markgraf said.

Campbell would often write a first draft, and Reed would refine it. The piece that gave Campbell the most difficulties was “Close.” In the song, Hannah starts taking hormone pills.

Hannah Before sings: “Is my skin really softer? Is my face really fuller? Am I just imagining it? / More pills. / Months. / No, I’m not imagining it.”

Because Campbell had not gone through a transition himself, Reed kept suggesting changes and sharing her experiences.

“There were just minor changes to (the song),” Campbell said. “It’s not as if you take hormones and you wake up and you’re a girl. It’s a very slow process, and the body is revolting against it. It doesn’t know what this new thing is until finally the body and the mind and the heart meet and say, ‘Yes, your skin is growing softer, and yes, you’re now emerging as the person you were meant to be.’”

Campbell also drew from his experiences as a gay man, and that’s how the song “To know” came about.The piece follows Hannah as she sees someone on television and begins to learn that there is someone else like her.

“Kim would just encourage me to find those moments that I felt, as a gay man, as the ‘other’ in society, like the person who is outside of society because of my sexuality,” Campbell said.

Reed and Campbell wanted to make Hannah as human as possible, which meant incorporating humor into the character. They said adding humorous aspects to the opera would make it more accessible to the audience and would help make attendees more comfortable.

“They’re coming in there really scared that we’re going to show a penis getting hacked off,” Campbell said. “When they come to an opera about a transgender person, they’re really so afraid that it’s going to be all about genitalia.”

Kaminsky, Reed and Campbell also wanted to depict this journey as a joyous one, which is reflected in the libretto and the music. Too often, the media presents transitioning as a horrible, torturous experience, Campbell said, when it is really a journey of joy.

“The change that Hannah makes, it’s a big change, and it is not an easy change, but it’s also not that different from someone saying, ‘I’m moving to New York because I will meet people like me,’ ” Campbell said. “We all make big changes in our lives, and we all make big changes to achieve happiness. And that’s why I think this story is universal.”

The score of the opera reflects a wide range of styles, Kaminsky said. She composed it to further reflect the journey Hannah goes on — from youthful innocence to confusion to discovery to commitment. Because it’s a journey, Kaminsky said there is a “propulsive” movement to the music, and Kaminsky made the music more dissonant and angular in the stressful moments of Hannah’s life.

The opera’s music is performed by a quartet that is positioned on stage with the performers as a way of “breaking down a lot of the standard expectations around opera,” Kaminsky said. When composing As One, Kaminsky assigned the middle voice of the viola, which she said is often buried in string quartets, to represent Hannah.

“There’s a soulful viola melody that keeps getting transformed throughout the piece,” Kaminsky said. “That’s kind of her pure inner self saying, ‘This is really who I am, and there’s some darkness here, but I’m yearning to be who I am.’ ”