Review by Melissa Kuntz:

The 19th century artistic Realism movement, with a capital “R,” reacted to the lofty themes in Romanticism and history painting by, instead, truthfully depicting common laborers and ordinary people in everyday surroundings engaged in common activities. Ever since, we often assume any realistic art is the representation of objects in a way that is accurate, true to life, unedited and naturalistic. And, we habitually make misguided assumptions that realistic artworks are authentic, credible and faithful to “reality.”

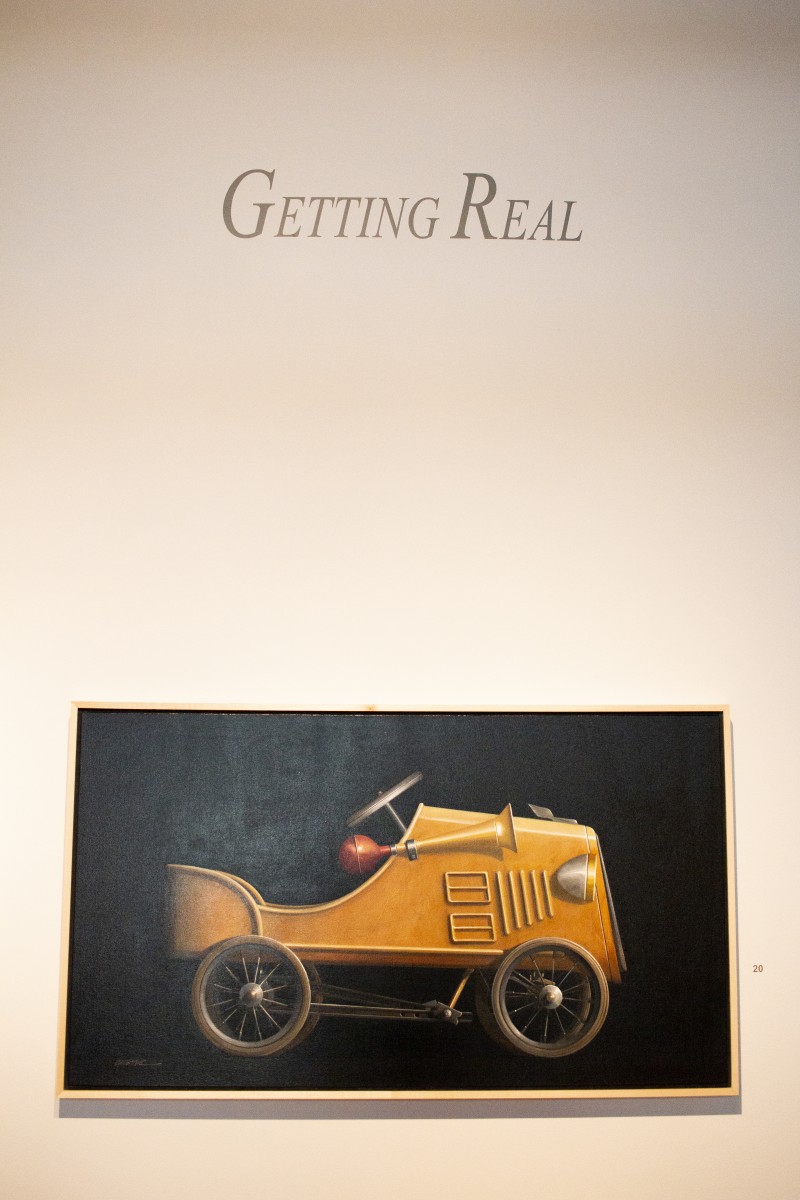

Curated by Judy Barie, the Susan and John Turben Director of VACI Galleries, “Getting Real” features paintings and sculptural works that are rooted in realistic representation of objects and landscapes. Barie’s goal for this exhibition was to balance abstraction and realism without pushing the imagery to one side or the other. So, where does this “abstraction” manifest itself in a gallery filled with clearly recognizable objects like toy cars, flowers, animals and buildings? And how do the artists obfuscate the “reality” presented in their works?

The human brain is wired so that when it sees something incomplete, it attempts to create a “whole.” The Gestalt principles of perception state that the brain will perceive things as more than simply the sum of sensory inputs, and it will do so in predictable ways. Especially relevant to the work of William Steiger is the Gestalt concept of “closure,” which states that we organize our perceptions into complete objects, rather than a series of parts. For example, given segments of a circle, we will perceive it as a whole circle, not what it “really” is — just a series of lines.

Steiger plays with this concept in his meticulous and precise paintings and collages of buildings set within voided landscapes. “Wheat Pool #12” is the perfect example of the Gestalt phenomenon at work. This oil-on-linen painting, at about 30 inches wide, shows two grain elevators in strong contrast against a white background with only a hint of the horizon behind. Naturally, we assume these are complete, truthful depictions of the structures. Yet, very careful examination reveals that the white, highlighted sides of the buildings do not have boundaries. There are no marks to distinguish where the building ends and the sky begins. Yet, we are amiss to see Steiger’s landscape for what is it — essentially an abstraction of shapes and lines — and our well-trained brains invent a completed scene. Similarly, in “Tank Capacity 2400 bbls,” the assumption that the girders supporting the tank are arranged in a logical order is contradicted when closer inspection reveals that they are largely random, abstracted and impossibly arranged.

Using abstraction as a means to realism materializes in Stanley Bielen’s flower paintings. Peonies are portrayed with the thick, random and layered brushstrokes most often associated with Abstract Expressionism. Yet, their small-ish scale, about 20 inches high, and floral subject matter are the antithesis of the machismo and epic scale of Abstract Expressionist works.

Shelley Reed uses Northern European art from the mid-17th through 18th centuries as the inspiration for her work. At this time, there was a developing interest in science, nature and the animal world. Animals were anthropomorphized and works were epic in scale. Reed’s paintings are monochromatic, often with a flat black background. Using grayscale, with luscious paint application, she is able to render the details of the flowers and animals with striking precision. Yet, we must remember that a grayscale is simply a convention that we have come to understand as representing dark and light; reality is never actually so precise. Each individual petal, feather or bit of fur rendered by Reed is a small value scale — all of these small abstractions coming together in convincingly hyperreal objects.

Elizabeth Fortunato casts from glass common objects that carry a sense of nostalgia such as spools of thread, keys, pin cushions and skeleton key-hole covers. The glass is delicately colored, but retains its translucency, giving the objects a ghostly presence. Taken out of context, some of these objects become abstractions. The stunning installation, “3rd From the Left & 2nd From the Left,” is a series of 24 key hole covers, the kind found in historic homes and often made of brass or cast iron. Fortunato has cast them in subtle colors of greens, blues, grays and sepia and arranged them in an oval shape hung on the wall. From a distance, the piece is a series of abstracted shapes, but up close, the details emerge and lead the viewer to imagine the homes from where these came. Fortunato mentions her love of casting as it is a multi-step process; she spends hours with each object and becomes familiar with the form, their significance and imagines the people who used them.

Wendy Chidester paints obsolete machines, lost through time and advancing technology. The objects, although their usefulness has passed, are beautiful in form and craftsmanship. An antique cash register, toy cars and a bubble gum machine are depicted in her oil-on-canvas works. Chidester captures the surface textures of the objects with a deft hand. She does this by scratching into the surface, flicking paint and applying multiple glazes; up close, sections of the canvases appear as painterly abstractions.

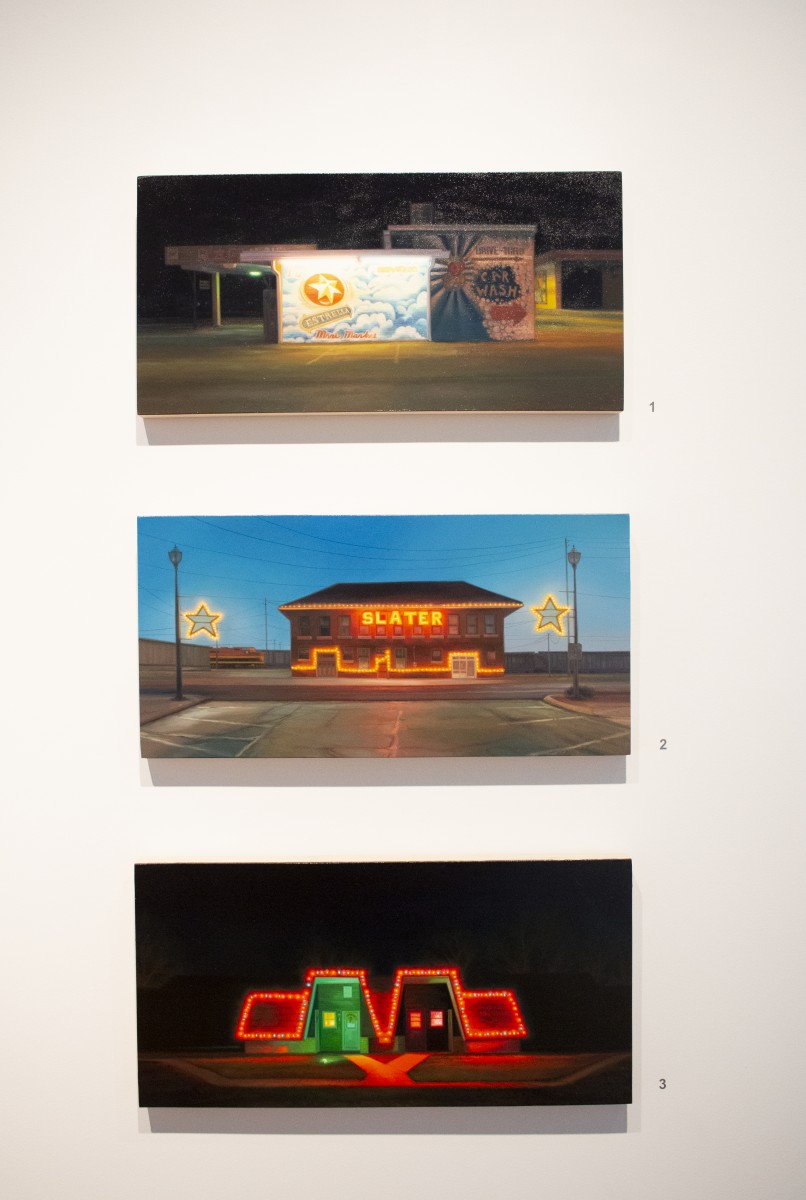

Finally, Sarah Williams and Leslie Lewis Sigler develop painterly surfaces with lush, virtuoso brush marks. Williams paints predominantly mid-century buildings artificially lit at night. The buildings are de-contextualized, with no other structures, people or cars within the scene. This gives them a sense of timelessness; they could have been painted from photos taken this year or 50 years ago. “North Glenstone Ave” is an oil-on-canvas, approximately 36 inches wide; Williams’ paintings are not epic in scale, rather they are intimate and personal, like portraits of the structures. The neon light in this painting casts an unearthly pink and orange glow onto the painted lines of the parking lot and the fluorescent light from inside forms halos around the windows. The colors are so well studied — the cement of the parking lot is rendered in purple and the building is a pink-to-yellow gradient. The scene in the window is simply a series of abstracted gray and mauve marks that coalesce into recognizable forms.

Lewis Sigler works in a similar fashion, creating incredibly well-observed still lives of silver platters and utensils. Each object is alone in the canvas against taupe or gray backgrounds. All the images are life-sized, making them relatable, as we might remember someone having a similar spoon or plate. Lewis Sigler’s paintings are, up close, tiny abstractions. They are reminiscent of the work of Janet Fish because the realism is a result of seemingly random and expressionistic brush marks. Reflected in the silver objects painted by Lewis Sigler are colors from the surroundings and a figure — perhaps the artist herself — abstracted in the center of a silver platter. This sense of nostalgia, which appears in the works of Lewis Sigler, Williams, Chidester and Fortunato, presents another theme which ties together the work of the artists in the show.

This exhibition presents the viewer with gorgeously rendered and sculpted art works that replicate familiar imagery, but within each artist’s work are more complex themes, techniques and concepts. Each artist utilizes tropes of abstraction in their interpretations of realism and the works are much more than initially meets the eye.

Pittsburgh-based Melissa Kuntz is a professor in the Department of Visual and Performing Arts at Clarion University of Pennsylvania. She holds an MFA and an MA from SUNY Purchase. She has been writing art and book reviews since 2002, for publications such as the Pittsburgh City Paper, Canadian Art Magazine, The Chautauquan Daily and Art in America Magazine.