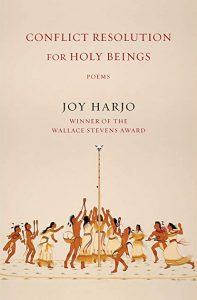

Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, invited poet Joy Harjo to speak at Chautauqua Institution long before Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden appointed the award-winning writer and musician to the United States’ 23rd Poet Laureateship, a role that counts Louise Glück, Natasha Trethewey and Tracy K. Smith among its alumni. All Atkinson knew was that the collection on which they had asked Harjo to speak — Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings — was “extraordinary.”

“She is considered by many to be the greatest living Native American poet,” Atkinson said. “We can look to the recent anthology, New Poets of Native Nations, which takes as part of its framework (the question), ‘Who are the poets who came of age and started publishing after (Sherman) Alexie and Harjo?’ as evidence of that (belief).”

Harjo, who is of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation, is the first Native American to serve as U.S. Poet Laureate. She will commence her official consultant duties in the fall, marking the beginning of the Library’s annual literary season with a reading in the Coolidge Auditorium in Washington, D.C., four weeks after closing the CLSC’s 2019 programming with a reading from Conflict Resolution, her 10th collection.

As the final CLSC author of the 2019 season, Harjo concludes a season of “Collaborations” at 3:30 p.m. Thursday, August 22 in the Hall of Philosophy. Inside a final week interrogating the intersections of race and culture, led by Wynton Marsalis and Jazz at Lincoln Center, Harjo — who is herself a vocalist and saxophonist who has toured with the Arrow Dynamics and Poetic Justice bands — reminds the American public of the crucial role that Native Americans play in the history of jazz.

“I think it’s exciting any time you are able to hear from a U.S. Poet Laureate in person,” Atkinson said. “But (the collection and the week’s theme) have come together to make it a triply exciting occasion. The very best part of all is that living at the center is a poetry collection that I would recommend any Chautauquan to read, regardless of CLSC selection.”

Stephine Hunt, manager of the CLSC Octagon and one of the leaders of this week’s Brown Bag conversation on Conflict Resolution, has read the collection twice, most recently in a one-hour sitting before Monday’s discussion on the porch of the Literary Arts Center at Alumni Hall. She described the book as a convergence of poem, song and prayer — a slim book that “isn’t dense” but still encompasses everything from a “strange pastiche of hurt and rain” to an island “formed / from desire and fire.”

Divided into four parts — a number with sacred significance for the Mvskoke/Creek Nation, Hunt noted — Conflict Resolution subverts popularly held conceptions of jazz and the blues, considering the latter as both a genre and a color reclaiming the synergistic relationship between song and poetry.

“Traditionally, poetry and the performance and production of poetry was musical,” Hunt said. “(Harjo) challenges those connections by adding an indigenous element; she strays away from Western canonical notions of poetry, and reshapes it through conversations about indigenous ceremonial pieces and through indigenous structures and lyricism.”

In the poem, “In Mystic,” Harjo writes, “There is still burning though we live in a democracy erected over the burial ground. / This was given to me to speak. / Every poem is an effort at ceremony.” It is within this effort that Hunt finds a “stunning” intertwined history of the human and more-than-human world.

“There’s a very prominent line of conversation and thought (in Conflict Resolution) that’s addressing the idea of coming home and finding home both spiritually in the soul, in yourself and as an indigenous person who’s been displaced from her homeland … through physical displacement or, historically, through genocide,” Hunt said. “So what does that mean to come home, to seek a home if it may no longer exist in some capacity? That (idea) is just peppered throughout this collection.”

The collection’s title piece advises readers to remain connected to ceremony and to home, and to avoid enacting violence on the world and the beings who inhabit it.

“(Harjo) is really saying that the resolution for these human conflicts, and conflicts beyond the human, is to listen and to listen broadly,” Hunt said.

Like Atkinson, Hunt hopes that one day, Harjo’s band will play the Amphitheater stage.

“If you ever get the chance to listen to some of her music on YouTube, do,” she said. “It’s worth it. There’s a small part of me that really hopes she brings her saxophone.”