“What to me is the Fourth of July?” asked the Rev. Traci DeVon Blackmon. “Will its great principles and social justice be extended to people like me? We live in a nation where freedom has been muted by praxis.”

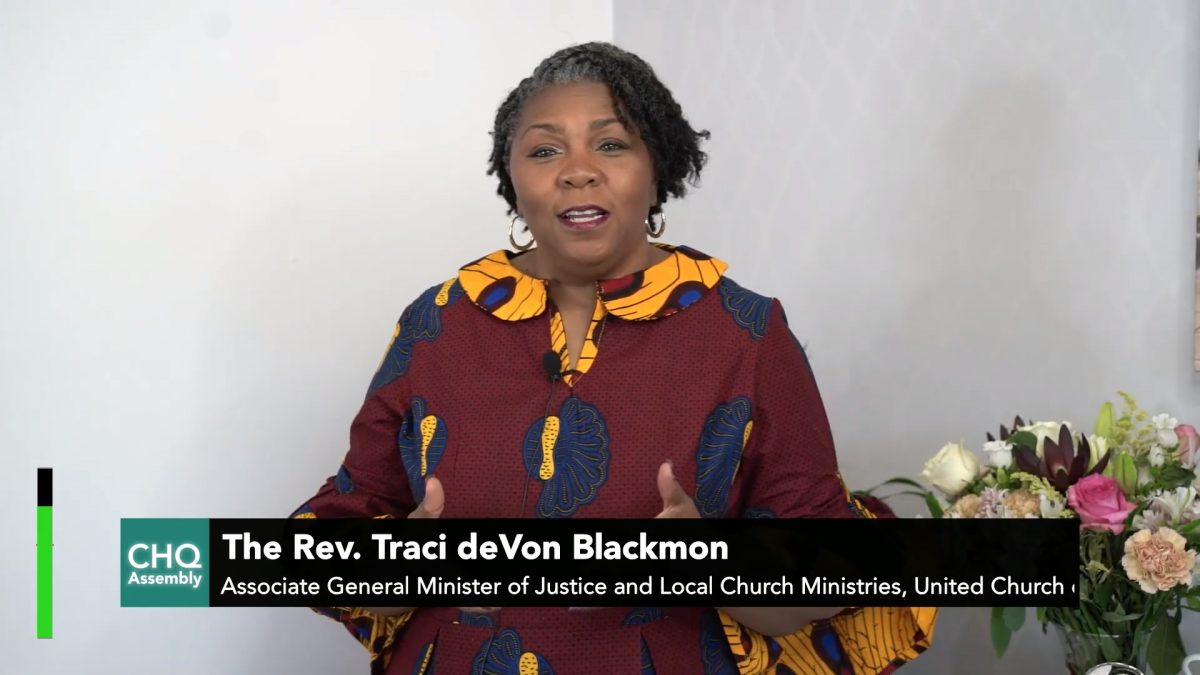

Blackmon preached at the 10:45 a.m. EDT Sunday, July 5, service of worship and sermon on CHQ Assembly. Her sermon title was “We, too, Sing of Freedom.” Her text was Luke 1:46-55 (NRSV), which she recited from memory.

“And Mary said, / ‘My soul magnifies the Lord, / and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior, /

for he has looked with favor on the lowliness of his servant. / Surely, from now on all generations will call me blessed; / for the Mighty One has done great things for me, / and holy is his name. / His mercy is for those who fear him / from generation to generation. / He has shown strength with his arm; / he has scattered the proud in the thoughts of their hearts. / He has brought down the powerful from their thrones, / and lifted up the lowly; / he has filled the hungry with good things, / and sent the rich away empty. / He has helped his servant Israel, / in remembrance of his mercy, / according to the promise he made to our ancestors, / to Abraham and to his descendants forever.’”

“Stories and narratives are crafted contextually, socially and politically,” Blackmon said. “How we see these stories may be different, but we see God in all our understandings.”

Blackmon cited Frederick Douglass’ keynote address from July 5, 1852: “What to a slave is the Fourth of July?”

“He acknowledged the great ideas of the Fourth of July and the hypocrisy of those who enslaved people. I read it every year,” she said. “Freedom remains as distant now as it did then; 168 years later we are struggling with actualizing the freedoms promised.”

She did not deny that progress has been made but said that “equity is not found for the whole (nation). In this confusing and chaotic time, The Magnificat, Mary’s Song, is a text that speaks to us.”

Mary was a member of a poor community that knew religion and politics were intertwined, a people who were familiar with the “divide and conquer” tactics of the ruling class. “There was competition and strife among those who should have been working together,” Blackmon said.

In the midst of this chaos, Mary lifted her voice in song.

“When we concentrate on the syrupy sentimentality of Jesus’ birth, we miss the revolutionary act of God choosing an African, Semitic, Palestinian child, living in a police state to sing against the empire,” Blackmon said. “There was injustice built into that society, too, what Audrey Lorde called hierarchies of oppression.”

Mary sang a song of freedom at a time when the 90 percent of poor people of color were controlled by the 10 percent.

“What does it mean today,” Blackmon asked, “with COVID-19 choking life out of communities of color? What an in-breaking of God (in this song), of love and life,in a community where freedom has not come.”

Mary’s song of hope turns everything upside down. “I grasp for this hope; it is meant for us,” Blackmon said.

The mother of Jesus is often seen as quiet and passive. “Luke sees her as a prophet of the God who shakes up the status quo,” she said. “It is an announcement of God’s revolution and revolution does not come in a time of peace. This announcement will change the order of how we think, act and live.”

She continued, “God chose a 13-year-old girl from a fourth-world country with dark skin, dark eyes and nappy hair. She was a doulos, a servant/slave girl. She is Sally Hemmings, Harriet Tubman, Sojourner Truth, a mother caged at the border, an essential worker with no protective mask.”

Blackmon urged the congregation not to get caught up in the poetry or “loveliness” of the words. “It is a revolutionary song, a song of freedom that turns the world upside down. Don’t miss the power of the moment,” she said.

If you miss the moment, she told the virtual congregation, “you miss the movement of God. God respects, exalts, feeds, remembers and helps the poor. God shows up for the poor. Mary’s song is the introit to an economic, political and moral revolution.”

When Jesus first declared his mission to his synagogue in Nazareth, he quoted the prophet Isaiah. Jesus was anointed to preach good news to the poor, free the captives, recover the sight of the blind and let the oppressed go free.

“The Magnificat is for those who are left out, locked out. It is the womb ready to birth a new song,” Blackmon said. “It connects us to the past, to Miriam, Deborah and Hannah. It is in the present and brings us an expectation of things to come.”

God is on the side of those who are left out, those on the borders, those without a safety net, those on the bottom, wherever they are found. God triumphs through the revolutionary act of love.

Blackmon quoted the Rt. Rev. Desmond Tutu from his book God Has A Dream. Tutu wrote that a child of God has to truly understand that God loves everyone. God does not share our hatred of our enemies. God’s love is too great to be confined. “Our prejudices are absurdly ridiculous in God’s eyes,” Tutu said.

“That is how God triumphs,” Blackmon said. “Jesus came to transform those who hurt and those who do the hurting. This is how we combat the evil ingrained in the structure. The Magnificat speaks truth and freedom because it tells of the inbreaking of Christ and its echo is heard wherever injustice is found.”

There is an echo of the Magnificat in every generation. She said, “It is found in Ferguson, in Staten Island, on a swing in Ohio, in schools in Pakistan. We will sing it even with knees on our necks.”

The tune for the song is not “The Star Spangled Banner,” or “America the Beautiful,” she said. “It is ‘Sing a song full of the faith that the dark past has taught us / Sing a song full of the hope that the present has brought us / Facing the rising sun of our new day begun / Let us march on ’till victory is won,’” she said.

Mary’s Song came forward again when George Floyd was killed. “Mary’s Song is what the Fourth of July is. I will keep singing, I must sing, until freedom truly comes,” said Blackmon.

The Rt. Rev. V. Gene Robinson, vice president for religion and senior pastor of Chautauqua Institution, presided from the Hall of Christ. Joshua Stafford, interim organist for Chautauqua Institution, played the Tallman Tracker Organ. Michael Miller, a Chautauqua Opera Apprentice Artist, served as vocal soloist. The organ prelude, performed by Stafford, was “Fugue on the Magnificat,” by Johann Sebastian Bach. Miller sang the gathering hymn, “Holy, Holy, Holy.” The anthem was “How Great, O Lord, Is Thy Goodness,” by Julius Benedict, sung by Miller. The offertory hymn was “I Love to Tell the Story,” by Kate Hankey, sung by Miller. “Magnificat in D,” by Charles Villiers Stanford, was the offertory anthem with Miller as the soloist. Miller sang the choral response “Nunc Dimittis.” Stafford played “The Stars and Stripes Forever,” by John Phillip Sousa, for the postlude. This program is made possible by the Mr. and Mrs. William Uhler Follansbee Memorial Chaplaincy and the Robert D. Campbell Memorial Chaplaincy Fund.