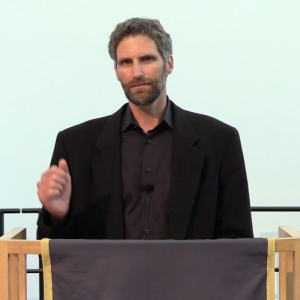

When Hartford Seminary President Joel N. Lohr finds it hard to pray, he doesn’t seek words of strength from the Bible or another religious text. He refers instead to a line from “This Spinal Tap,” a 1984 mockumentary about an English rock band.

“I will rise above it, I’m a professional,” says the character Nigel Tufnel, who is played by Christopher Guest in the movie.

Lohr makes a point in poking fun at himself, about not taking himself too seriously and learning to truly know himself.

Speaking with others outside of his religion and worldview, Lohr said, helped him understand himself and others more than any other human interaction.

This was the topic of his lecture “Finding Myself in the Other: Learning from Those Outside My Faith,” which was released on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform at 2 p.m. EDT on Wednesday, July 8. It was recorded during the week of June 28 on the grounds of Hartford Seminary, a nondenominational theological college in Connecticut. Following the lecture, Chautauqua Institution Vice President for Religion and Senior Pastor Gene Robinson spoke with Lohr in a live Q-and-A on behalf of the audience, who could submit questions for the live Q-and-A at www.questions.chq.org or on Twitter with #CHQ2020.

Lohr felt like an impostor while studying in higher education. Before he went to college for an undergraduate degree, he had trained as a carpenter. The only reason he pursued a Ph.D. was because a professor believed in him.

While in the basement of a library as a Ph.D. student, Lohr’s Ph.D. mentor spooked him — Lohr’s mentor intimidated him even when he did expect to see him — and recommended a book.

“Have you read Joel Kaminsky from Smith College?” Lohr’s mentor said. “He’s a scholar who knows who he is.”

Lohr didn’t know who Kaminsky was, or who he was. But he wanted to.

“Taking life and taking yourself too seriously keeps us from being who we should be,” Lohr said. “To be human helps us love oneself and others.”

When his daughter was around 3 years old, Lohr and his wife had started to teach her lessons from their Christian background, in addition to inspiration from Jewish religious thought. Lohr was focusing on the Jewish idea to love God with your mind, your soul and with everything you have, and Jesus’ addition to this principle to also “love thy neighbor.”

He asked his daughter, “What is the most important thing God wants us to do?” hoping she would intuitively say something from scripture.

“To laugh,” she said.

He didn’t correct her. This was just as important.

Lohr at first thought that he would complete his personal journey through studies of his own faith, but he realized he grew closer to knowing himself through encounters with others who don’t share his faith.

All of these stories involved risk, involved becoming vulnerable,” Lohr said. “In doing so, I came to understand the other. And in doing so, I came to understand myself and hopefully become a better person.”

One specific encounter was when he was a multifaith chaplain at a university. The school’s Muslim association didn’t have a supervisor, so Lohr was recommended as one. To offer a learning opportunity for himself and others, he created a multifaith event for students to present on their different faith beliefs.

A Muslim student, Farhiya, discussed her life in California as a Muslim who wears a hijab.

“My jihad has been great,” she said.

Lohr asked her if she could provide context for the word jihad, which means “struggle” in Arabic, since not everyone would know the true meaning. Then Lohr asked what her specific jihad was.

“My headscarf is my jihad,” Farhiya said.

Lohr asked for more details, thinking she was forced to wear it. But the truth was that she grew up in a moderate Muslim home, and her mother did not wear a headscarf. When Farhiya decided to wear one when she went to college, her parents worried for her safety as an identifiable Muslim in the United States.

Her jihad was going against her parents’ wishes because of the headscarf.

In another encounter, Lohr ate lunch with another Muslim student in the cafeteria. When they both sat down at the table to eat, Lohr was uncertain of what to do. Should they pray together? Should he say nothing?

“Do you pray before you eat?” Lohr said.

The student said he only did sometimes, but he always prayed after. He also thanked Lohr.

“What is a prayer you say for this?” Lohr said.

The student recited the prayer before repeating it in English.

“Well, let that be our prayer today,” Lohr said.

Hearing this distracted the student from eating. The student had never been asked questions like this by someone outside of his faith before.

In a class Lohr was teaching at Hartford Seminary, a Muslim student from Indonesia expressed her gratitude for the class trip to a Jewish synagogue, because she had never had a chance to meet a Jewish person in Indonesia. Her name was Ani.

Months later, another student from the class had invited students and staff to a Shabbat dinner at her home. Another student asked how she prepared the meal.

“I’ve had help all day,” the Jewish student said. “Ani helped me prepare. She was here at 8 a.m. this morning, and we chopped vegetables. And we put things in the oven. We worked together all day together on this meal.”

This was a moment for Lohr.

“Was Ani any less Muslim in that moment? Was the Jewish student, Gilana, any less Jewish in that moment?” Lohr said. “Absolutely not. They were coming to know who they were more fully through the other.”

The last story Lohr told was about a study abroad group he led in Italy to explore various religions, art and cultures. The group, which came from different backgrounds with and without faith, toured the Vatican with another student group they didn’t know. During the tour, the two groups merged and made small talk.

Mo — a nickname for Mahmood, who is Muslim — was speaking with someone from the other group. Mo asked him what the group was doing.

“I’m here to learn about Islam and how to deal with it,” the student said.

Mo looked to Lohr briefly with confusion as Lohr listened in on their conversation.

The other student didn’t know that Mo was Muslim, and Mo continued asking about the group. What were they doing? What were they learning?

The student was part of a fundamentalist Christian group that was in Italy specifically to learn about Islam and how to convert Muslims to Christianity.

Mo’s grace stood in sharp contrast with the horror on this other person’s face when he found out he had unkowingly said this in front of a Muslim.

“It’s OK. I understand,” Mo said. “At least you’ve met a Muslim. Have you met many Muslims? Have you been to the mosque here in Rome? Maybe we can go together.”

They never had the chance to go, but it was another story that highlighted how vulnerability allowed for growth in everyone involved.

“All of these stories involved risk, involved becoming vulnerable,” Lohr said. “In doing so, I came to understand the other. And in doing so, I came to understand myself and hopefully become a better person.”

Instead of thinking about what someone outside one’s religion might see, Lohr said, “What might we see in them?”

To explain this, he quoted Luke 7:9, when Jesus speaks with a Roman centurion soldier — an enemy of the Israelites — who humbly asks for Jesus to not even enter his home, but to just say a word to heal his partner.

“Never have I seen such faith as I have seen in this outsider,” Jesus said.