When George Floyd lost his life at the hands of a white Minneapolis police officer, the world didn’t stop. Instead, it marched. It chanted. It ignited.

Before 2020, the 2017 Women’s March held the record for American protests at 4.6 million attendees. Polls indicate that, as of mid-June, more than 21 million adults had attended a Black Lives Matter protest.

Nicoletta Berry, an incoming masters student at the Juilliard School of Music and recent graduate of the Manhattan School of Music, wanted to stand in solidarity through song — and decided to create her own way of honoring the moment.

“The more outspoken we are, the better things are going to be for the future of us all,” Berry said.

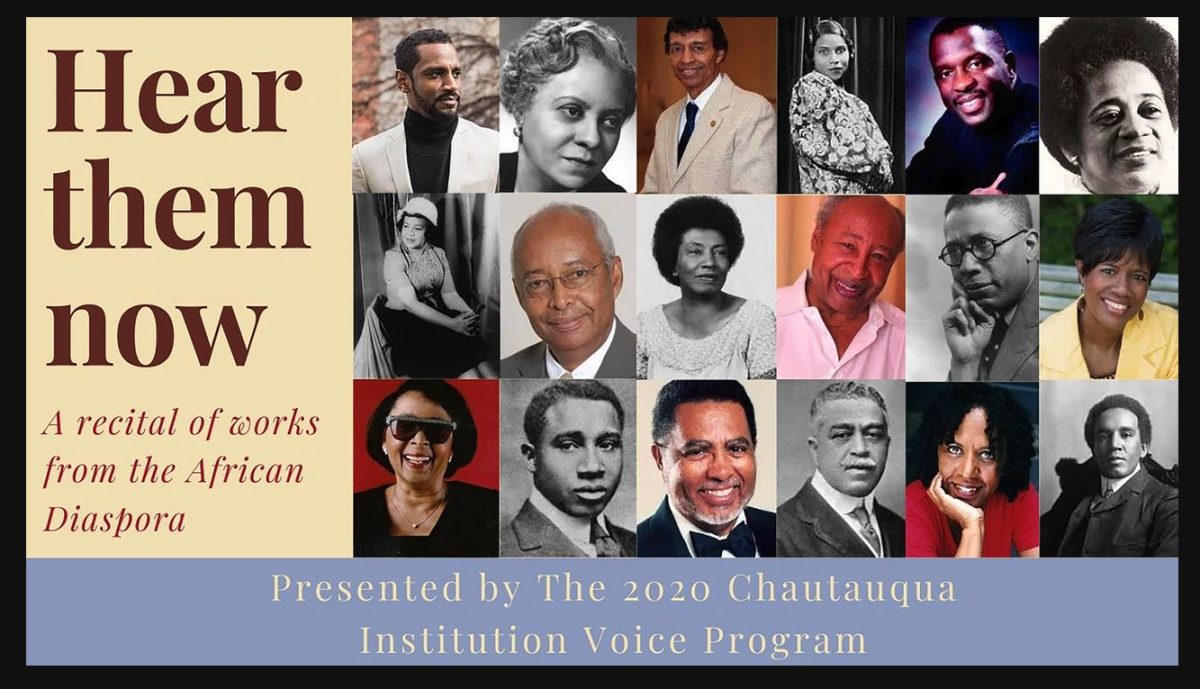

“Hear them Now: A Recital of Works from the African Diaspora,” a School of Music Voice Program recital, is available on-demand on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform. The recital initially aired and was recorded Sunday, Aug. 2, on Zoom.

To ensure the planning and execution of the recital was as diverse and representative as possible, Berry reached out to Jaime Sharp, an incoming masters student at the University of Cincinnati’s College-Conservatory of Music and recent graduate of the University of Michigan.

“I didn’t want this to be yet another thing run by people who are not Black,” Berry said. “We have seen way too much of that recently.”

After they sent an email to every student in the Voice Program, 18 students volunteered to perform in the recital. Berry and Sharp put together a program of 18 solos, including art songs, spirituals and arias. All composers are Black. None of them repeat.

“We feature an Afro-Latino composer, living composers, late composers and female composers — we basically checked as many boxes as we could,” Sharp said.

There are staples in the set, Sharp said, such as Harry Burleigh, the first African-American composer acclaimed for his concert songs as well as for his adaptations of African-American spirituals, and Hall Johnson, whose Hall Johnson Choir is responsible for many of the greatest choir performances on stage and on screen in the ’30s and ’40s. But there are also contemporary additions, like Carlos Simon, whose work is contemporary partially because of its versatility, partially because he’s only 33.

It can be difficult to get a hold of music by Black composers, according to Sharp. She has been to music libraries where none of the Black anthologies were accessible, and one where it was listed in the catalog, only for Berry to be told the library was “unable to locate it.” Berry has two anthologies of her own, but was hesitant at first to approach the repertoire because of her limited knowledge of Black composers.

“Those kinds of things just aren’t good enough anymore,” Sharp said. “The failure of these institutions to provide this kind of repertoire is hurting us as students. I hope now that a lot of the singers have heard this music, things begin to change.”

Things are changing already. Sharp and Berry gave each student who performed access to all of the included compositions and said many students expressed they were eager to include it in classes and performances during the subsequent semester. Sharp said a vocal coach from her school now wants to include some of the pieces into his American art song class.

“The first step is being exposed to them,” Sharp said.

Berry said 18 students is merely a starting point. Most music students across the nation have never explored Black repertoire, something Sharp finds difficult to make sense of.

“… When you sing American music, that is now going hand in hand with white American music,” Sharp said. “We just want to normalize the concept of when you have to perform an American art song, the one you pick just happens to be an American art song by a Black composer, by a Black woman.”

Normalizing the repertoire, for Berry, means appreciating the work of William Grant Still and Scott Joplin just as much as that of Franz Schubert and Robert Schumann. But for too long, Sharp added, classical music has been deemed “white Eurocentric music,” which she said is narrow and not true, a view she hopes “Hear them Now” will broaden and “alter for life.”

“How can we incorporate this Black music in the future not because we have to, but because it’s amazing and it deserves to be performed?” Berry said. “I want people to listen to this recital and realize it’s not this foreign thing — it’s here and it’s always been here and we have the obligation to nurture it, perform it and to offer it to the world.”