The words “refugee” and “immigrant” are not interchangeable — the first word has often been used in the media to describe victims of horrifying circumstances, and the second, as a way of preserving the mythology of the American dream.

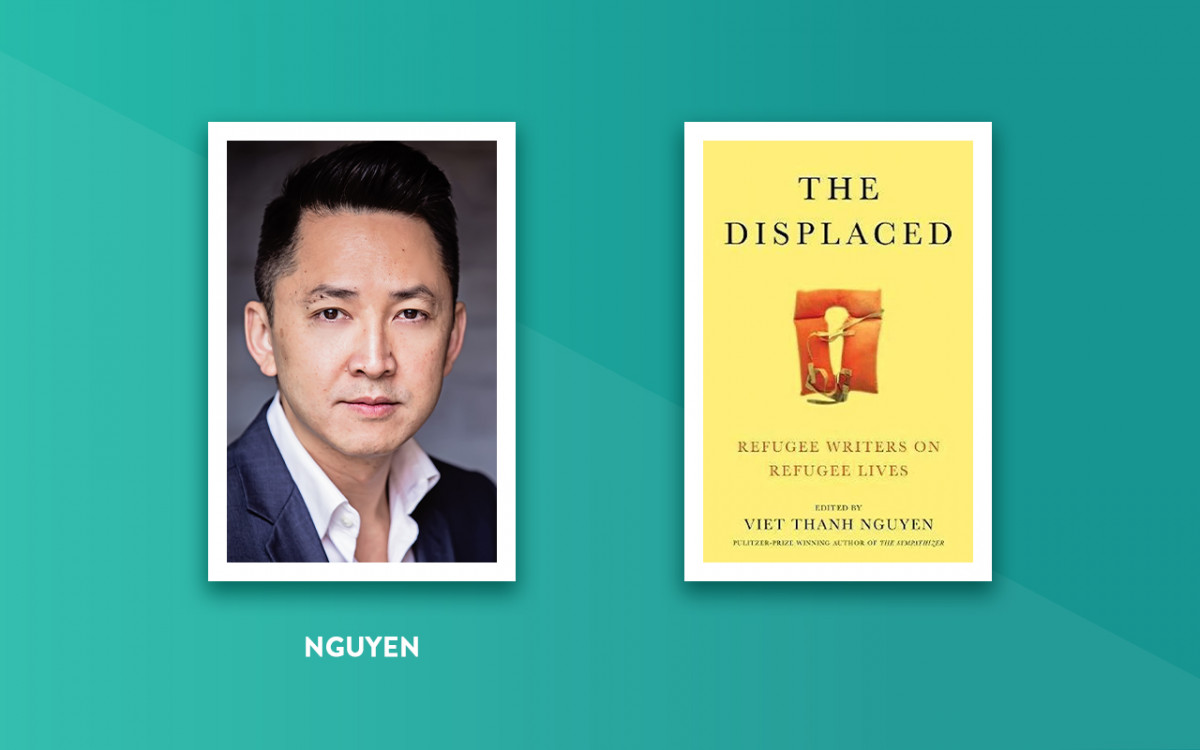

“Refugees are definitely a more stigmatized group of people,” said Viet Thanh Nguyen, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Sympathizer and a professor of English, American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California. “Yet at the same time, it’s crucial to talk about them, not simply to draw more attention to them and turn them even more into objects of pity, but to think about what the forces are that created refugees.”

Nguyen said immigrants, on the other hand, are a group of people that “make us feel better,” because they affirm the ideas of the United States as being a welcoming, hospitable place where upward mobility is possible.

“Refugees, however … are often created due to the things that we do that are really terrible, like wars and dictatorships that we support,” he said.

One of Nguyen’s latest projects, the book of essays The Displaced: Refugee Writers on Refugee Lives, which he edited, will form the basis of the last Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle presentation of the 2020 season at 3:30 p.m. EDT Thursday, Aug. 27, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform. The Displaced features 17 refugee writers from across the globe shedding light on their experiences. Proceeds from the book support the International Rescue Committee.

“The essays in The Displaced revolve around the authors’ own refugee experiences,” said Sony Ton-Aime, Chautauqua’s director of literary arts. “They are curious, deeply personal and wide-ranging. They do not concern themselves with policies, but with the struggles and triumphs of individuals. Therefore, The Displaced does not aim, I believe, to explain the refugee question; instead what it does is lift the refugee identity to reveal the human.”

All the writers in The Displaced talk about their personal histories, and about how they came from refugee backgrounds and work with refugees, Nguyen said.

“These stories were alternately moving and inspiring and troubling because of what they had been through, or witnessed,” he said.

In particular, Nguyen said that one of the essays by Kao Kalia Yang — a former CLSC author herself, and a 2017 Chautauqua Prize finalist — titled, “Refugee Children: The Yang Warriors,” was particularly moving.

The essay, he said, was about Yang’s experience as a Hmong refugee from Laos and the early years of her childhood that she spent in a refugee camp in Thailand.

“These refugee children were forced to grow up much faster than they would normally,” he said. “They had to go find food for their families and turn that into a game and into a fight. Stories like that are really heartbreaking, but they’re not uncommon.”

The ubiquity of stories like Yang’s — and like Nguyen’s, who at 4 years old came to a U.S. refugee camp with his parents after the fall of Saigon — is something crucial for people to understand, Nguyen said.

“These stories are happening not just in refugee camps, but in our detention centers on our border,” he said. “So it was very important for me to include Reyna Grande, who is not technically a refugee as classified by the United Nations. But in my mind, she, as an undocumented migrant forced to leave from Mexico to the U.S., having her family and personal life ruptured with long-term consequences — that, to me, is a refugee existence.”

One of the issues Nguyen said he wants to bring up is the process by which someone gets classified as a refugee, and who doesn’t, a process he said is often a political maneuver.

“One thing that writers like me can do is bring attention to some of these stories that refugees have faced, and are facing now,” he said.

This program is made possible by the H. David Faust Leadership Fund.