JORDYN RUSSELL – STAFF WRITER

It’s been a little more than 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment. “Tenacity” works to commemorate this milestone, and Chautauqua Visual Arts Galleries chose to honor contemporary female visual artists with raw talent and creativity through this exhibition, showcased in the Gallo Family Gallery of the Strohl Art Center until Aug. 24. Originally planned for the summer of 2020, the exhibition was postponed until this season in an effort to broaden audiences and to again meet in person.

“Tenacity” is defined as the “quality or state of being tenacious.” For the women that paved the way back in 1920, tenacity was a familiar quality. A tenacious woman holds her ground, stays determined, and never gives up.

The artists featured in this exhibition are Lucy Fradkin, Raheleh Filsoofi, Bovey Lee, Beth Lipman, Shervone Neckles, Carol Prusa and Jackie Tileston – all women that have had accomplished careers in the world of visual arts. The “Tenacity” that these seven female artists display inspired Judy Barie, the Susan and John Turben Director of Chautauqua Visual Arts, to curate this exhibition.

“It is not that they are just tenacious, but they certainly do have tenacity, intelligence and vision, as well as a well-crafted hand with each medium that they (use),” Barie said. “These women are all rock stars in the world of art, artists in their mid-to-late 40s and on, that have an amazing reputation.”

Their artwork serves to honor women of the past, present and future, celebrating the true strength of will and perseverance demonstrated by their forebears and contemporaries. From disparate mediums to paintings to large glass installations, there is something available for all tastes in this exhibition.

“They are a creative force, holding positions as thought leaders, educators, curators, directors, performers, art critics and many other undefinable roles,” Barie said. “This was the way I wanted to celebrate the passing of the 19th Amendment, by giving these women an exhibition.”

Beth Lipman, a glass artist famous for her sculptural compositions, spoke with the Corning Museum of Glass about the powerful women who served as inspiration in her journey to becoming an artist.

“My grandmother considered herself a technician, an embroidery technician, and my mother was an artist, so I grew up surrounded by creativity constantly,” Lipman said. “I am using glass specifically to discuss ephemerality and the temporality of time, so I think that the materials really warrant use for (this) type of discussion.”

After realizing she wanted to be an artist at the age of five, Lucy Fradkin followed in the tradition of genre painters, although self-taught. Fradkin tells artistic stories by placing diverse women in “domestic settings,” according to her website.

“The figures are quiet and inactive, which contributes to the solemn and mysterious atmosphere of the scene,” Fradkin said. “My work is clearly inspired by the traditional, but the impact of personal history is evident in the quiet presentation of issues of gender and race.”

Although Brooklyn-based Fradkin’s work focuses on her personal history, she wants the audience to be able to create their own personal narrative, although it may not align with her own distinctive vision.

“Ultimately it’s the viewer that brings the last part of the art to life, creating their own narrative,” Fradkin said. “I often find that people ask me questions like, ‘Why is there a plate of deviled eggs on the table?’ They strive to find a hidden meaning, when in reality, I just liked the way it looked visually.”

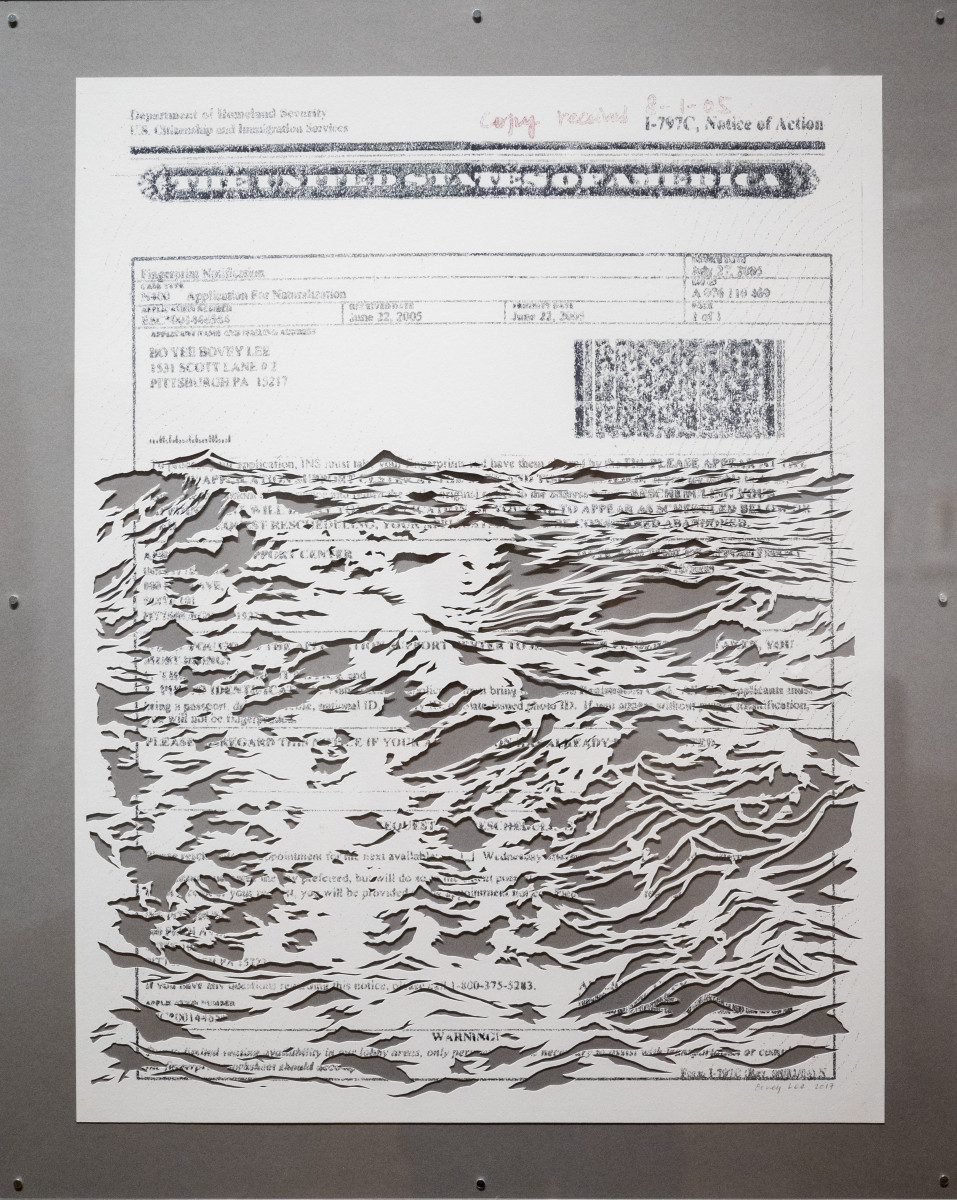

Bovey Lee, known for her hand-cut paper and site-specific installations, centers the focus of her artwork on “migration and its impact on our shared humanity and the environment,” according to her website.

When Lee decided to display her artwork in this exhibition, she said that she initially felt inspired by Barie’s curatorial concept.

“This curatorial concept gave me a way to honor my mother, to honor the community of immigrants, and to honor the history of this country built on immigrants,” Lee said. “It took me 11 years to become a U.S. citizen, which is why I really focused on the immigration process and experience associated.”

Lee’s works of art, like “Rice Cooker & US Flag” and “Application for Naturalization,” work together to tell an immigration story that is complex yet equally straightforward.

“The centerpiece is called ‘Application for Naturalization,’ which was the very last document sent to me by the Department of Justice (now Homeland Security). The most important is the green card, as it is the last stage,” Lee said. “Using phototransfer, I made the document bigger, which also blurs the image a bit. Although unintentional, it was a happy accident.”

Lee recalls this “happy accident” as a metaphor for a distant memory, as she went through the immigration process quite long ago. After the long winding journey Lee faced, the blurring and enlargement caused by the phototransfer worked to encompass her entire experience as an immigrant woman.

“The rice cooker, left of the centerpiece, was given to me by my late mother,” Lee said. “It’s accompanied by a U.S. flag sitting to the right, which all the new immigrants received at a ceremony in Washington, D.C. to become a U.S. citizen.”

Los Angeles-based Lee said this rice cooker holds a special place in her heart. Coincidentally made by the brand National, it was given to Lee before she departed for the U.S from Hong Kong.

Lee emphasizes the importance of family relationships and lineage in her artwork, as people wouldn’t exist without the ancestors who came before them. When she received the rice cooker from her mother, she believes the baton was passed onto her.

“When the rice maker broke after using it for decades, it changed functions from just cooking rice into a work of art,” Lee said. “I had to keep this memory with me, as it created an artifact filled with history. It represents the relationship between mother and daughter.”

Lee’s artwork marks the beginning, middle and end of her own individual immigration story. Despite this, she hopes to honor the audience’s free way of interpreting something of interest or intrigue, such as her works of art.

“Freedom is about honoring each person’s own take on things,” Lee said. “Art is very generous, because even though we may never meet or talk, we each carry our own story or relationship with the artwork in a poetic and beautiful exchange.”

Fellow artist Carol Prusa echoes this sentiment in her artwork, likewise transformed by the life-changing experiences detailed on her website. Known for her meticulous silverpoint technique and use of unexpected materials, Prusa uses her artwork to bring awareness to the impact we leave on our globe.

“I seek to communicate what cannot be seen but felt — the vibrations that are part of us all, including echoes from billions of years ago,” Prusa said.

Jackie Tileston, an associate professor in fine arts at the University of Pennsylvania, similarly explores boundaries and states of being. On her website, she self-identifies her work as an attempt at a “unified field theory” of painting.

“My work as a painter is to knit the world together in a kind of visual globalism, (where) there is both a sense of idealism and anxiety that accompanies this endeavor — the desire to make a democratic garden of Eden, and concern about how to make sense of it and reconcile disparities,” Tileston said.

Drawing inspiration from her Afro-Grenadian-American identity, fellow artist and educator Shervone Neckles specializes in printmaking, sculptures, installation, textiles, book arts and social investigations. She employs her artwork to explore past and present-day colonialism, but also as a means to give back to her community.

Brooklyn-based Neckles has worked as a high school multimedia arts teacher, a consultant for the New York City Department of Education and an adjunct professor at the Pratt Institute. With this experience under her belt, she shifted gears and took a position as an artist programs manager for the Joan Mitchell Foundation.

“It really went full circle, from me trying to figure out what I could do to survive to then picking up a career that felt really natural to me,” Neckles said. “Then, doing (what) I wish I had more of when I was a child, which was having more teachers of color, and (to have them) teaching subject areas I was passionate about.”

Raheleh Filsoofi, an itinerant artist and female curator, also has artwork permeated with sociopolitical statements such as immigration and border politics.

“Filsoofi is on our core faculty here at the School of Arts,” Barie said. “The videos displayed in this piece were actually filmed in 2019, her first year here.”

Her piece, titled “Imagined Boundaries,” works to build a culture of communication through art. This piece was previously displayed at two parallel art shows, one in Iran and the other in the U.S. At each location, there was a series of boxes in a collage-like composition that called out to the viewer to look inside.

In the U.S., the people who looked out were Iranians. While in Iran, the people who looked out were Americans. With this artistic decision, Filsoofi challenged the viewer to set aside politics and recognize the humanity in everyone.

“In this specific showing of the piece, most of the people displayed in the videos pictured inside the artwork are actually from Chautauqua,” Barie said. “I think it is very endearing that she would do that for us.”

“Tenacity” is made possible thanks to the support of the Jerome M. Kobacker Foundation.