DAVID KWIATKOWSKI – STAFF WRITER

After more than a year of movie theater doors being closed, they are opening once again to allow filmmakers and moviegoers alike to talk about the passion that goes into making their favorite movies.

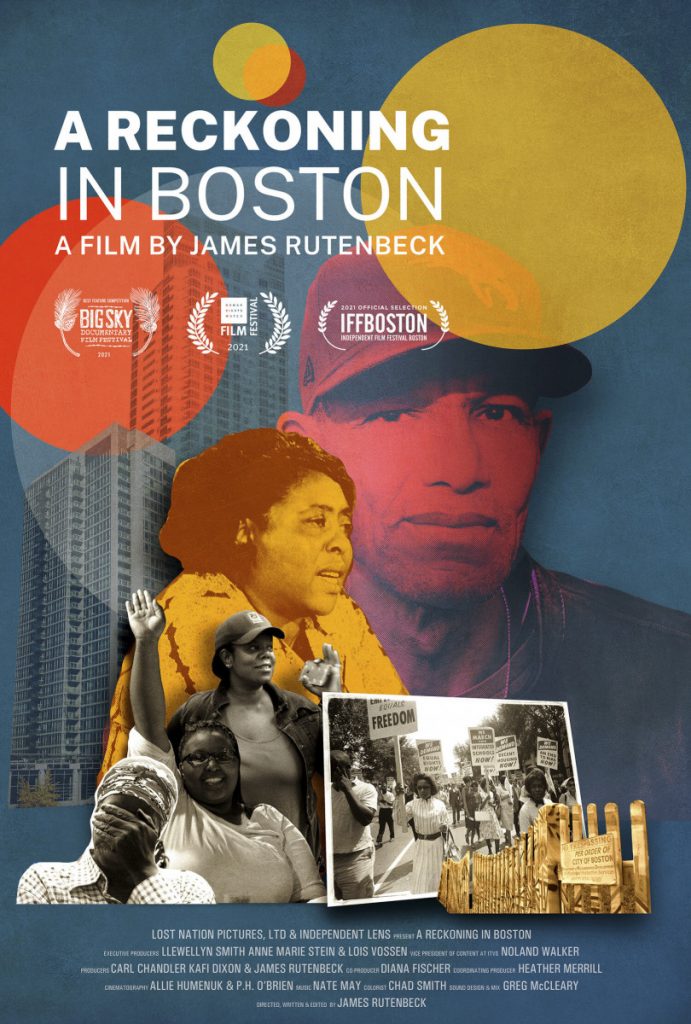

At 10 a.m. Friday, July 23 at Chautauqua Cinema, the first Meet the Filmmaker special event of the season will be taking place, accessible with a Traditional Gate Pass. Director James Rutenbeck will be presenting his documentary “A Reckoning in Boston” alongside one of the subjects of the film, Kafi Dixon.

Chautauqua Cinema owner Billy Schmidt is elated to bring back the Meet the Filmmaker series this summer.

“It’s a hard thing to wedge into place because the opportunities aren’t always there,” Schmidt said. “But when we can work one out, it’s such a pleasure to bring someone here to show their work. I think our crowd really appreciates it. Chautauqua loves the opportunity to ask a question on a mic.”

“A Reckoning in Boston” chronicles two individuals’ journeys through the Clemente Course in the Humanities. The course is taught in 34 cities across the United States for people who have experienced homelessness, are transitioning to life post-incarceration or who faced obstacles in getting a college education.

The mission of the Clemente Course is to foster critical thinking through engagement with history, literature, philosophy and art history.

However, as time went on, Rutenbeck had trouble finishing the film and was forced to come to terms with his own white privilege and complicity in the power structures of America. Dixon and Carl Chandler, two students within the Clemente Course program, were originally two of the subjects of the documentary.

As Rutenbeck pivoted the focus of the documentary, he enlisted Dixon and Chandler as co-producers; as Rutenbeck was awakened to the racism, violence and gentrification in the city of Boston, he essentially became a subject of his own documentary.

“I think it’s really daunting to really start to realize about racial structures and about racism as a white person and try to understand what can (be done) to dismantle it,” Rutenbeck said. “I think the film is helpful in that regard for people who care about (the) racial justice (conversation) but are maybe a little bit overwhelmed by the idea of it and how they could participate.”

Dixon is a Black woman, an urban and rural farmer and a generational New Englander. She also founded Boston’s first Cooperative for Women and its first worker/owner urban farm food co-op, also known as the Common Good Cooperatives.

“I did not believe, that without James as a white man and his camera and the power that existed in those two designations, that anybody would have understood that there were Black woman trying to develop a co-op …,” Dixon said. “I felt that we would be lulled into this basic sense of complacency once again — that everything is well for everybody and that the powers that be would not ever witness the granular issues that we experienced on a daily basis.”

The relationship between Dixon and Rutenbeck was one of mutual education and discovery in one another.

“I didn’t realize that there was systemic violence, systemic bias,” Dixon said. “I didn’t realize that my experiences, the violence and the trauma were based on anything that had to do with biases around my race, my gender or my class. It wasn’t until I tried to do something that I thought would be received as good, that I realized that it was good in the bigger picture.”

Schmidt believes that Chautauquans will benefit from seeing perspectives different than theirs and that it’s something that film does best.

“We can cerebrally get the idea that people are in very different positions, but as by human nature, we only see ourselves from our we see life from our own positions, our own point of view,” Schmidt said. “(Film critic Roger) Ebert said before he died that movies are a machine that generates empathy. This movie is important in Chautauqua because it takes you across that divide.”