NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

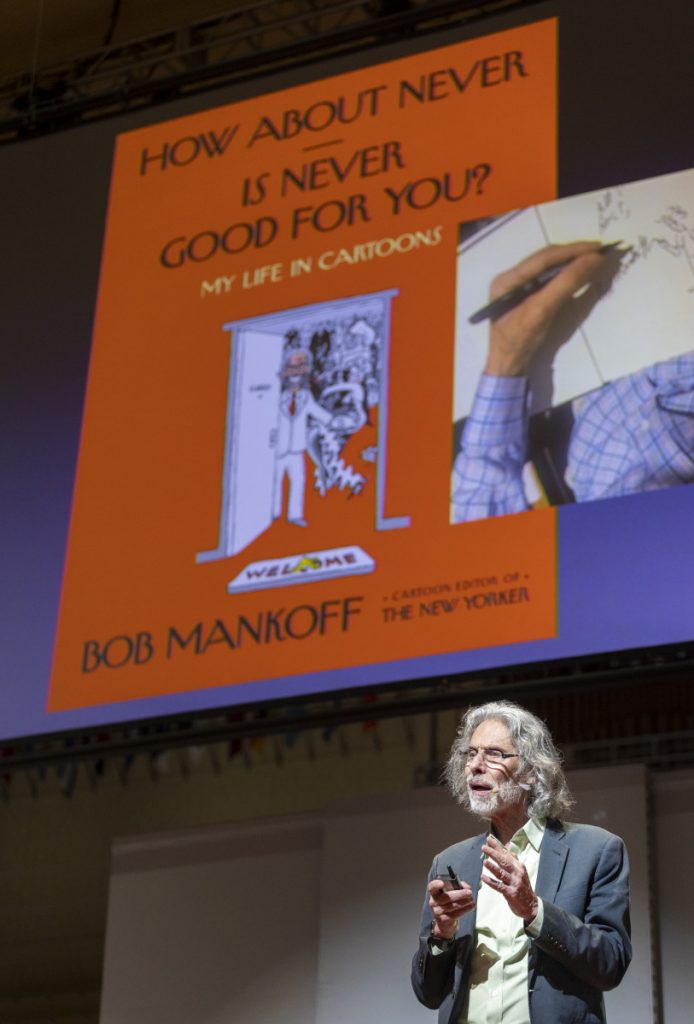

A singular cartoon gave Bob Mankoff the money to put his daughter through college. It’s of a businessman on the phone, looking at a planner. The caption reads: “No, Thursday’s out. How about never — is never good for you?”

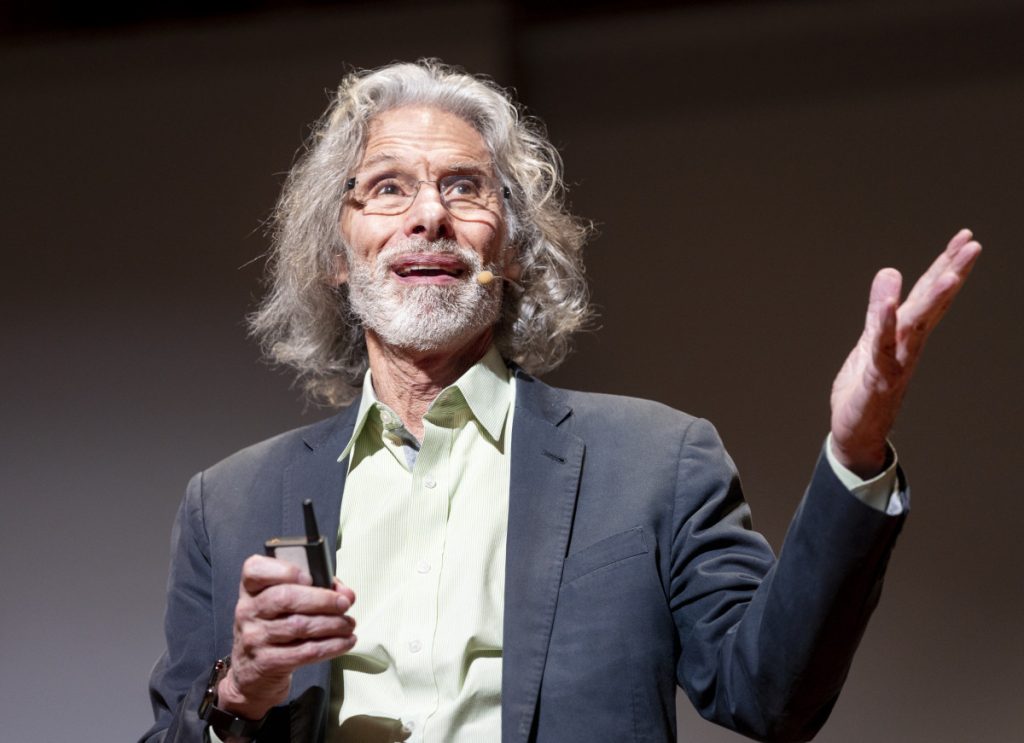

Mankoff, the former comic editor of The New Yorker, said comedy helps people cope with growing older. Mankoff shared three jokes he came up with when he turned 70.

“I’m 70. The good news is, it could be worse. The bad news is, it will be.”

“I’m 70. The good news is, 70 is the new 50. The bad news is, dead is not the new alive.”

“When you’re 70 and you’re a guy, you wake up stiff everywhere but where you want to be.”

Now, at 77, Mankoff runs a website called cartooncollections.com, the largest online compilation of cartoons in the world which serves as the definitive archive and online store for cartoons. He also runs the humor section of the online magazine Air Mail. At 10:30 a.m. Thursday in the Amphitheater, Mankoff presented his lecture, titled “Laughing All The Way: My Life In Cartoons,” as part of Week Five’s theme of “The Authentic Comedic Voice: A Week in Partnership with the National Comedy Center.” He explored his life journey and career path, as well as the ins and outs of creating cartoons.

Mankoff grew up Jewish, but he said he didn’t get his jokes out of the Talmud. He got them from the Catskills — listening to Jewish comics like Rodney Dangerfield, Jerry Lewis and Buddy Hackett.

“When I was courting my third, last and best wife — who is not Jewish — I thought I was having this normal conversation. She said, ‘Why are you arguing?’ and I said, ‘I’m not arguing, I’m Jewish,’ ” Mankoff said. “There’s an old saying, ‘Two Jews, three arguments.’ I think that arguing, that frame of mind, is part of what’s essential to humor and comedy.”

Mankoff didn’t become a comedian because there were few accessible comedy clubs during that time. So instead, while attending the High School of Music & Art, Manhattan, he doodled a lot — particularly with dots, one of the first styles he developed as a cartoonist.

“This is something I would just do. I have no idea why I did it, but I did it. So I drew these kinds of images to pass the time,” Mankoff said. “Later, that would actually become my style.”

Next to Mankoff in his senior yearbook was Edward Burak, who in his picture held a pipe. Mankoff looked him up later and realized he is now called the dean of American pipe makers.

“Then I thought, ‘What could I have accomplished?’ ” Mankoff said. “I saw him with a pipe, I could have stole that bit. I could have been the dean. But that wasn’t the case. ”

Instead of creating pipes, Mankoff went to Syracuse University. He showed a picture of himself in college.

“People look at that picture and say, ‘Did you do drugs?’ And what I say is, ‘Not enough,’ ” Mankoff said. “If I had a time machine, I would go back and do — not a lot, but more than I did.”

In graduate school, Mankoff studied experimental psychology. He never went to class, except for tests, and one day he walked into the final late, wearing leg weights — because, he now thinks, he wanted to be able to dunk a basketball. He took one of the blue books, sat down, and the instructor came over and asked who the hell he was. Mankoff said, “I could ask you the same question.”

“This whole class, in their blue books, breaks into laughter,” Mankoff said. “It’s just so great — because humor is a kind of courage to say the joke. And for that moment, you’re liberated. For that moment, all of the bullshit is blown away.”

Later, Mankoff was on the cusp of earning his doctorate — “the world’s longest cusp,” he said. He knew he wanted to quit and become a cartoonist, but his parents wanted him to get a job.

Eventually, they loosened their expectations. Mankoff’s mother said she didn’t care what he was, as long as he was the best. He could even be a garbage man.

“I said, ‘You know, Mom, in New York City, there are over 12,000 garbage workers. That’s hard. That’s really hard, to be the best. You ever see how some of these guys can unload and identify garbage from non-garbage?’ ” Mankoff said.

His father considered Mankoff’s proposed career, but he said newspapers “already had people to do that.”

“I said, ‘But one of them might die. All I got to do is read the obits. And then I’m johnny-on-the-spot, and I got that guy’s job,’ ” Mankoff said.

Mankoff quit psychology and began pitching 10 to 15 cartoons a week to different newspapers. The Saturday Review was one of the first publishers to accept his cartoons. It was of a jester chained in a cell, telling the guard, “Please tell the king that I remember the punchline.” It took him around eight hours to draw this particular cartoon in his early dot style.

And he used a technical pen during this time. Sometimes students ask Mankoff what kinds of pens he uses, and he always says, “Get one with ideas in it. The pen is not the critical thing here.”

“I submitted and submitted and submitted to The New Yorker between ‘73 and ‘77. Now sometimes I say I submitted 2,000 cartoons and sometimes I say 500. I don’t know,” Mankoff said. “Rejection, rejection, rejection, I had my whole bathroom papered with (rejection letters).”

Like many young artists, Mankoff got his start by being influenced by and imitating other artists — in his case European cartoons. These ones didn’t have captions and had a far-reaching audience because, like silent movies, they could reach anyone no matter what language they spoke.

These wordless cartoons often relied on logic and piecing together the joke. He shared a few: one was a man who was eating his breakfast and reading a newspaper that was coming straight out of a printing press, and another was a woman carrying three buckets, two labeled “H” and one labeled “O.”

Later in his career, Mankoff switched to relying more on captions. One cartoon he shared was of a man and woman in a living room. The caption read, “I’m sorry, dear. I wasn’t listening. Could you repeat everything you’ve said since we’ve been married?”

“One of my ideas is just to take something and exaggerate it to its endpoint,” Mankoff said. “It’s a truth that comes out through exaggeration, and a lie, in a way.”

Another cartoon he created had the caption “Yes, you did catch us at a bad time.” The drawing was of a man, hiding at the side of a couch, answering the phone, while his wife shoots a gun at him. Another was a man and a woman in a bed, and the man asks, “What do you think of some-sex marriage?”

Sometimes Mankoff will know there is a joke somewhere within a common phrase, like “same-sex marriage,” and be patient.

“I’ll write the phrase down, and that joke will not be there immediately,” Mankoff said. “Eventually your unconscious mind, when you’re a comic or comedian or cartoonist, is always, always working on it.”

Mankoff, like many cartoonists and comedians, will often make jokes about current events and issues.

“I don’t try to hit it straight on,” Mankoff said. “I try to look at it a different way. I’m not an editorial cartoonist. I try to look at the human foibles behind it all.”

Comedy naturally targets hard topics like health care, he said, because humor is always about sadness.

He then showed a cartoon of people waiting in line to get into heaven, obviously impatient, while in the background, others zoom through a gate labeled “E-Z pass.” Another cartoon’s caption was “The military’s solution to last week’s puzzle.” The drawing was simply “KABOOM.”

“You are mashing up different frames of reference. You’re putting things together that don’t usually go together,” Mankoff said. “I think John Locke said judgment is about making very fine distinctions between things that are very close. Humor is about bringing things that are very disparate together.”

Mankoff had several rules when he judged cartoon submissions for The New Yorker. The first: originality is overrated.

“What people like is novelty within a frame that they’re used to,” Mankoff said. “That’s why all jokes sort of sound like other jokes in some way.”

Every art relies on clichés, from love songs to action movies, and he said every artist uses a common cliché at least once in their career.

The second rule was to play favorites, as in favorite cartoonists. The audience wants to see the same people again and again, as well as see them grow as artists, but this plays into the next rule: Not so much that nobody else gets to play.

His last rule was to keep in mind location. The New Yorker, he said, was an empathetic newspaper that covered harsh topics, so the bar is much higher than in other publications.

The Rejection Collection specifically publishes cartoons that would never make it into The New Yorker, such as a ventriloquist, drunk, whose puppet is also throwing up.

He ended his lecture by stressing simplicity, with a simple cartoon. It was of a sign that said “Stop and Think,” and two people saying, “It sort of makes you stop and think.”

“I hope I have made you stop and think a little bit, but more importantly, laugh,” he said.

As part of the Q-and-A session, Chautauqua Institution President Michael E. Hill asked Mankoff how the digital age has changed the cartoon field.

Mankoff said the rise of the internet has created a mix of a golden and lead age for cartoonists. On one hand, cartoonists can reach such a wide audience now without the need of going through a publisher. On the other hand, most of the money their work creates goes toward social media sites, and not the artists.

This is one of the reasons Mankoff created cartooncollections.com. His website helps artists copyright their own work, and also earn money.

Hill asked Mankoff what his advice is to young people dreaming of becoming cartoonists or graphic designers.

“I would often say, especially if there were young people in the audience,” said Mankoff, to the laughter and applause of listeners. “I didn’t mean that joke. For you, it’s too late. But, there’s always reincarnation, next time around.”

He said it is hard, that they would have to put in as much energy as possible when they are young and have the energy to stay up late and meet deadlines.

“The office will always be there. Don’t do the office first. Use your energy for it,” Mankoff said.

He quoted Wayne Gretzky: “You miss all the shots you don’t take.”

“As a parent, you should definitely let them take that shot, support them,” Mankoff said. “You’ll really never regret it because some of them will be successful and they’ll be eternally grateful to you for giving them that chance.”