NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

While Mao Zedong was radically egalitarian, his successor, Deng Xiaoping, was more practical. He helped open China up to the world and convinced its people to let some among them become wealthy first. The rest of China would follow naturally.

Dexter Roberts, a fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Asia Security Initiative, said Deng was very successful over the next several years. Too successful, some thought, to the point his own successor was worried the wealth gap between China’s rich and poor was becoming too big.

This is one of the main problems that China faces today, Roberts said. China is now tainted with wealth gaps even greater than the United States.

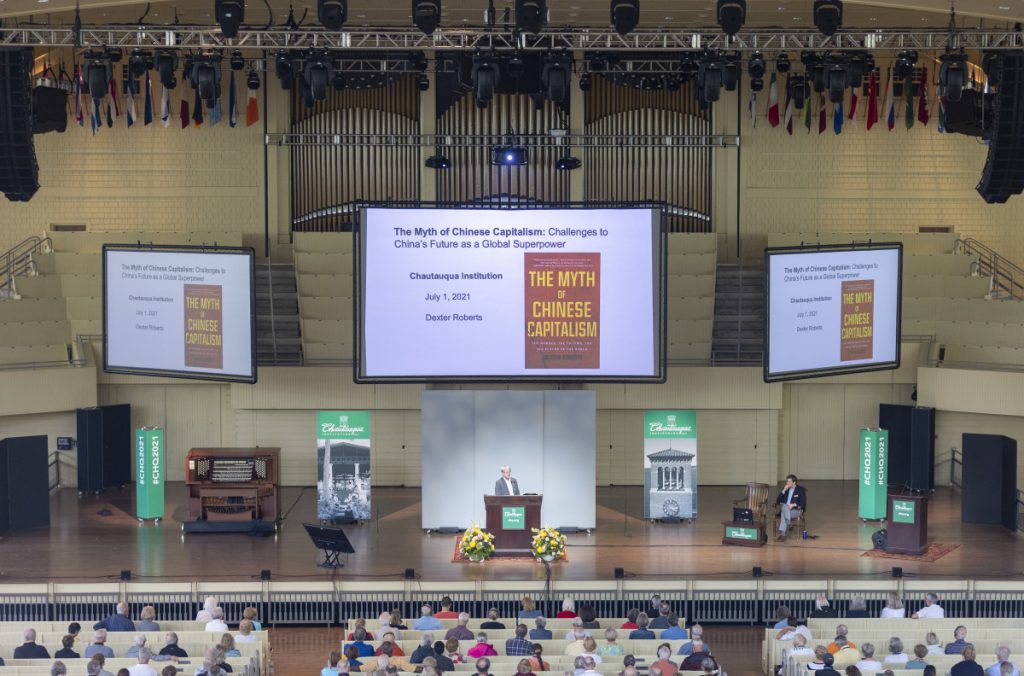

Roberts reported in China for over two decades for Bloomberg Businessweek, is a fellow at the Maureen and Mike Mansfield Center at the University of Montana, where he is also an adjunct instructor of political science. At 10:30 a.m. on Thursday, July 1 in the Amphitheater, Roberts delved into China’s uncertain financial future and the hurdles 300 million internal migrant workers face. His lecture, titled “The Myth of Chinese Capitalism: Challenges to China’s Future as a Global Superpower,” was the last presentation of the Chautauqua Lecture Series Week One’s theme of “China and The World: Collaboration, Competition, Confrontation?”

In 2000, Roberts reported on China’s young migrant workers. He met many of these people in Guizhou, often called the factory of the world because it has the world’s highest number of exports, from clothes and toys to iPhones. One of those migrants was Mo Pubo.

Mo left his village when he was 15 before starting high school and spent the next five years traveling around China working at factories. He eventually landed in Guizhou, where he met Roberts.

Roberts talked to Mo’s coworkers, many of which were his distant cousins, and also Mo’s girlfriend.

“She had been very shy. She had always seemed afraid. When I addressed her, she would look down at the table,” Roberts said. “It was quite the experience to then see her several months later back at her village. She was really transformed. She was actually pretty proud of her village.”

Mo’s girlfriend returned home for two reasons: Her parents needed help during the rice harvest, and her identity card expired.

This ID is more important than one might think, not only to migrants like Mo, but to the future of the Chinese economy. It states where a person is born within China. According to Chinese law, a person cannot use health care, public education or pension funds outside of their birth area. This means that the 300 million workers must travel back to their homes in order to receive medical care. Similarly, they must send their children back home for their education, or pay high prices for private urban schools.

And it is a large risk to have an expired identity card. One of Mo’s cousins was held for ransom because theirs had expired.

“In places like Guizhou, the local police often saw migrants as a source of extra income. They would get them on the streets for any infraction they can pick up,” Roberts said. “Certainly an expired card would be one of the classic reasons they would grab someone. They would hold them in what they would call black jails and, in fact, hold them for ransom.”

Mao and his government initially created the card policy as a means of controlling the rural population and restricting migration across the country. Roberts said Mao wanted a “captive” rural population living in communes to produce cheap grains and foods for the urban population.

“The economic rationale was: Sacrifice the livelihoods of the Chinese rural people in order to support the city,” Roberts said.

Unlike Mao, his successor, Deng, allowed the rural population to travel and live wherever they chose. But, Roberts said, Deng still tied social welfare — like health care, education and pensions — to where each person is born.

“The issue here probably does not come as a surprise: China’s rural health care, China’s rural education, is far, far inferior to what is available in cities,” Roberts said.

Like in the U.S., the wealthier the area is, the more resources the local schools and hospitals have. With rural areas lacking the factories and foreign investments that urban areas have, villages are usually poor. A lot of the money that these remote villages receive, Roberts said, comes from migrant workers’ earnings and local agriculture.

In 2000, the average wage of people in urban China was three times the average wage of those in rural China. Today, the ratio is around 2.5 to 1.

Roberts said migrant parents can spend a high amount of money for private urban schools for children from rural areas, but even these schools are often not much better than their rural counterparts. Rural schools have a very high dropout rate; Roberts said very few actually finish high school in these areas. Furthermore, around 100 million children of migrant workers grow up separated from their parents.

China and its migrant workers are reckoning with the welfare rules around the identity card, but also with another Mao-era policy lingering into modern times.

In urban areas, homeowners are essentially free to sell, rent or buy their property and keep most of the profits. Roberts said this has led to an explosion of wealth within the real estate industry.

But, in rural areas, when owners sell their land, they receive very little because the local Party members take most of the profit.

The policies around the identification cards and selling property leave migrant workers with little money, and the extra money they do have, they need to save for emergencies. This is especially dangerous for the Chinese government because their economy is transitioning from factory- and export-geared to one that needs to be driven by the spending power of its own people.

China’s old economic model is not working as well, Roberts said, because the one-child policy has left the country with few working-age adults and factory wages have increased. China’s economy initially grew at unprecedented rates partially due to the very low wages the companies paid their workers. Since those wages have grown over time, China’s profits have decreased, and are still decreasing.

Additionally, migrant workers often save as much as 23% of their wages, which is 15% higher than the global saving average. It is either this, Roberts said, or risk going bankrupt.

So, China’s leadership wanted to increase its household consumption, Roberts said, which is at a very low 39%, 15 points below the world average. In comparison, Roberts said American household consumption is between 70 and 75%.

Matt Ewalt, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair of Education, opened the Q-and-A by asking why the Chinese government is resistant to expanding education to rural areas.

The main issue, Roberts said, is money, as funding for schools and hospitals comes from the local area. Another issue is that there is not much benefit for rural governments to invest in schools. Their reasoning is, Roberts said, if they invested heavily in educating children, the students would still leave for wealthier cities as soon as they come of age, instead of staying within the community. Urban populations also do not want to share their access to welfare, particularly with education.

“Some of the bigger protests we’ve seen in recent years (in China) have actually been the parents of city kids who have gone and protested against the well-meaning efforts by the central government to try and allow more young people from rural China to also attend these schools,” Roberts said. “We’ve seen parents go march outside of the board of education and say, ‘Keep them out.’ ”

And, Roberts said, President Xi Jinping is not a strong supporter of reform.

“He does not necessarily believe in allowing young people to decide to live where they want to live and to sell when they want to sell,” Roberts said. “So I think there’s a large issue of control by the Communist Party — this perception that it’s socially destabilizing to allow rural people to move around the country.”

With Week One of the CLS ending, Ewalt ended the lecture by asking who the audience should read to learn more about China’s role in international affairs.

Roberts recommended journalists and authors Peter Hessler, Ian Johnson and Mei Fong — a friend of Roberts’ who lectured at Chautauqua two days before him.