To policy scientists who seek to resolve complex public policy problems in the common interest and whose benchmark goal is human dignity, the late Eleanor Roosevelt is a rock star.

Not only did Roosevelt serve as the first chair of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, which drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but she also championed civil rights and social activism within the United States.

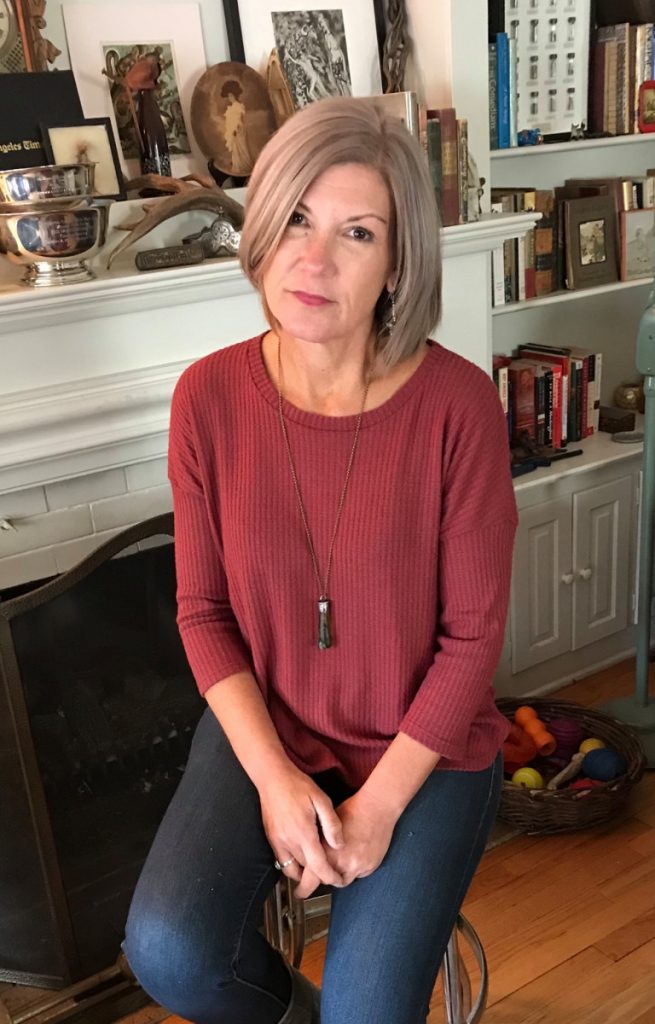

At 2 p.m. on Saturday, July 9, in the Hall of Philosophy, historian, prolific author and highly entertaining speaker Candace Fleming will give the second presentation in the Chautauqua Women’s Club’s weekly Contemporary Issues Forum series: “Eleanor Roosevelt: An Emblem of Hope.”

Fleming’s talk will draw from her extensive research for her book, Our Eleanor: A Scrapbook Look at Eleanor Roosevelt’s Remarkable Life, for which she received nine awards and honors, including Publishers Weekly Best Books of 2005, New York Public Library’s 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing in 2005, Parent’s Choice Gold Medal, and School Library Journal Best Books: 2005.

“Eleanor Roosevelt was influential,” Fleming said. “Where did all of that come from? (She was) an awkward, scared, fearful young woman. … My favorite quote of hers is: ‘No one can make you feel inferior without your consent.’ … She was still self-conscious at the end of her life, and still wrestling with not feeling (she was good) enough.”

Despite being a tall-tale-teller in preschool and a story writer since 7, becoming an author wasn’t something that Fleming had really thought about, according to her website’s biography, which she wrote.

College history courses revealed her passion. Fleming earned both her B.A. and M.A. in American history at Eastern Illinois University, “in a little town called Charleston, which is really seriously in the heart of (Abraham) Lincoln country.”

“I didn’t realize it then, but studying history is really just an extension of my love of stories,” she wrote in her website’s biography. “After all, some of the best stories are true ones — tales of heroism and villainy made more incredible by the fact they really happened.”

Marriage and children followed college graduation, and Fleming’s fascination with history continued.

“When I had kids, I was writing history articles for American History Illustrated, American Heritage and other places that wanted history, like the Chicago Tribune Sunday Magazine,” she said. “… And then I started writing history for young people, and I discovered that’s what I really loved.”

But, according to Fleming, “writing children’s books is harder than it looks.”

“For three years I wrote story after story. I sent them to publisher after publisher,” Fleming wrote in her biography. “And I received rejection letter after rejection letter. Still, I didn’t give up. I kept trying until finally one of my stories was pulled from the slush pile and turned into a book. My career as a children’s author had begun.”

Oh what a career! More than 40 books later — all edited by Anne Schwartz, the person who accepted her first story — Fleming’s in-depth historical research and engaging storytelling have earned her numerous awards, as well as appreciation from countless teachers and families.

Fleming’s Boxes For Katje (2003) won 22 separate awards and honors; Family Romanov: Murder, Rebellion, and the Fall of Imperial Russia (2014) earned 21; 17 for The Rise and Fall of Charles Lindbergh (2020); The Lincolns: A Scrapbook Look at Abraham and Mary (2008) won 11.

“I have a lot of ideas and I think about (them) all the time,” she said. “I have more ideas than time to write. I think, ‘a publisher might want to buy this, but do I really want to spend time with it?’ I have several topics that take years of research and writing. I always push those away; they’re too big. But, if (an idea) keeps coming back, if it nags at me — like with Eleanor Roosevelt — if it stays in my head, (I’ll write about it).”

Fleming appreciates the freedom having Schwartz as her long-term editor has brought her.

Being “lucky enough to be with the same editor, probably for 25 years now, if I have a project I say I’d like to do a book about, let’s say, Eleanor Roosevelt, (Schwartz) says ‘OK,’ ” Fleming said. “So, I don’t have to write it first (and then ask her). We’ve been together so long that she trusts me.”

Fleming is able to juggle two book projects at a time and said it has worked well for her.

“While I’m working with big books that take years, I write shorter books, mostly fiction,” she said. “It’s a right brain, left brain thing. Doing all that helps me creatively. … Writing a picture book is a lot of fun. You remember how to tell a story. It keeps my storytelling tools sharp while I’m figuring out how to tell that big nonfiction story.”

Over the years, the challenges of writing have changed for Fleming, especially recently.

The biggest challenge, “used to be trying to get my writing done with children at home,” she said. “Now, it’s about balance; I think it might be from COVID. How much work do I want to do, and how much time do I want for myself?”

Fleming said that publishing has shifted over the years, incorporating more researching and writing.

“Authors are expected to do our own and write blogs.,” she said “Suddenly your hours get filled up with not writing (books) because of the advent of social media. I’m not the biggest fan. … It used to be you could ‘just’ churn out a book and pop in at a conference. You didn’t have to do anything else.”

In fact, Fleming said that until about 10 years ago when Highlights for Children built its own conference center, she had come to Chautauqua Institution several times to speak at their annual conferences, which were held in July. She looked forward to them.

“Now, there’s a virtual book tour that you can do from your own house,” Fleming said. “Suddenly I’m making a video, a home video for marketing at Random House for its book launch. … But it’s not just a 30-second home video. It’s a neat (workspace), it’s putting on makeup — what’s that? — and also a dress. And you have to think about what you want to say, even if it’s just for 30 seconds.”

Finding balance between “What should I do?” and “What do I want to do?” has become increasingly difficult. Particularly so, one might surmise, for someone who has always had more ideas about what to write than actual time to write.

“I’m excited about Chautauqua and Eleanor,” Fleming said. “… What I’m going to do is tell seven stories about her, what people may not have realized she did, and (talk about) something she carried in her wallet her whole life.”

People may think that “nonfiction is like reading the encyclopedia, dull and dusty,” Fleming said. But, she knows how to make history come alive.

“My goal with nonfiction is to write a story so that it reads like a novel,” Fleming said. “Nonfiction is like the step-sister, yet these are true stories, and they’re entertaining and enlightening and they can change minds, opinions and viewpoints.”

Policy scientists embed Roosevelt’s humanity, as expressed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights drafted by the human rights commission she conscientiously chaired, in the goals they set for their public policy problem solving work.

Via anecdotes few people know, first-hand historical accounts and animated narrative, Fleming said she will show “how Eleanor Roosevelt’s decency, determination and generosity of heart changed the world; how her vision of a more generous world still lingers; and how her example matters now, more than ever.”