The weather was a little iffy, with the possibility of rain, Thursday, July 28, during the ecumenical worship service in the Amphitheater.

The Rev. Emma Jordan-Simpson reassured the congregation that if it did rain, she would do what her Aunt Doris did when Jordan-Simpson was a child.

“When rain or thunder threatened, Aunt Doris would tell us to ‘Get somewhere, sit down and be quiet. God is talking. Listen to God.’ When the storm was done, Aunt Doris would ask, ‘What did God say?’ ” Jordan-Simpson said.

On Thursday morning, her sermon title was “Praying in Motion,” and the Scripture reading was Matthew 6:5-13.

Jordan-Simpson had the honor of having a prayer she wrote included a book called Standing in the Need of Prayer: A Celebration of Black Prayer, published in 2003 by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. The book contains a collection of photographs that capture many aspects of Black spirituality, coupled with prayers from the Schomburg Center archives.

Coretta Scott King wrote the foreword to the book, and Jordan-Simpson read a paraphrased version of it:

“Throughout the epic freedom struggle, the great sustainer of hope is the power of prayer. From the slave ships, the auction block, the lash, people followed the drinking gourd,” Jordan-Simpson read. “When homes and churches were burned and bombed, people lynched by racist mobs, the sustainer of hope was the power of prayer to open hearts to God.”

“An open heart is how we make vital connections and overcome obstacles to discover God’s will,” she told the congregation. “King was convinced that prayer gives strength and hope of divine companionship in the struggle.”

Trust is an important part of our relationship with God.

“We have to trust God to be God in our real, messy lives,” Jordan-Simpson said. “As we walk with our neighbors and kin over the rough road, it is hard to be in relationship with ‘whosoever wills,’ but we are all in need of grace. We are not instruments of God’s will in the struggle for justice if we are closed off from the transformation of an open heart. The struggle demands an open heart.”

In the Scripture reading from Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus told the crowd not to “heap up empty phrases when they prayed.”

“Before we had a pandemic, we had an epidemic of closed hearts,” Jordan-Simpson said.

In 2018, AJ Willingham, who writes for CNN about trends in American society, published an essay titled “How ‘Thoughts and Prayers’ Went from Common Condolence to Cynical Meme.”

Willingham said that the phrase “thoughts and prayers” was repeated until it lost all meaning. It reached a point she called “semantic satiation,” and said not only did the words no longer have meaning, they became “something ridiculous, a jumble of letters that feels alien on the tongue and reads like gibberish on paper.”

“People with the power to make change can’t, and so they offer up ‘thoughts and prayers.’ The phrase is cruel, cynical, poisonous and shows a smallness of spirit,” Jordan-Simpson said. “It reflects the limitation of relationships and closed hearts.”

She continued, “People say the same words without any action. It would be different if they had no power, but they have incredible power.”

She gave an example of what people who are in pain hear when people with power say, “Our thoughts and prayers are with you.”

“Sally and I should probably feel devastated, but we don’t, because it is not happening to us or anyone we know. You don’t matter to us, and if you did we would effect change, but we don’t care,” Jordan-Simpson said.

Jesus taught the crowd that prayer was more than words. Jesus offered them a posture of prayer to emulate so they could be with each other and with God.

When Jordan-Simpson’s youngest child was 2 years old, she insisted on leading the family prayers at the dinner table.

“She would have us hold hands and would look around to see if our heads were bowed. If mine was not, she would say, ‘Mommy, bow your head,’ ” Jordan-Simpson said. “Then she would say ‘Our Father.’ That was it and then she would look at each of us to seal the prayer.”

Jordan-Simpson called this an act of coming together. Her child said “Our Father” not “My Father, just for me.” She made the name holy.

The world watches people of faith in prayer “performing, but God sees us,” Jordan-Simpson said. “It is the point of prayer to stand in companionship and trust with God.”

The Rev. Frank A. Thomas, in his lecture for the African American Heritage House on Wednesday, said companionship with God requires people to be naked.

“That makes me shiver,” Jordan-Simpson said. “Nakedness looks like deep dependence on God, requires deep self-awareness, a refusal to ignore the real circumstances of life. We have to bring the pain, death and hunger around us because they are the matter of our lives.”

God holds precious the lives of Indigenous people seeking water rights, Asian Americans who are victims of hate crimes and Black trans women whose murders are met with silence.

“God knows where God stands,” Jordan-Simpson said. “Our prayers are postured where we choose to stand with God.”

The Psalms, she said, are honest communications of companionship with God.

“My husband and I will have been married 34 years in August,” she said. “He is the one person I have to be honest with. I might not want to be, but I have to be.”

The Psalms show that the people of Israel trusted God with their rage, despair, revenge and joy. They trusted God to hold these emotions with them so they could expect to just be human.

“We have to stand ready to be in God’s presence so we don’t waste God’s time,” Jordan-Simpson said. “God cares more about us than the words (we use). It is not what we say to God, but where we stand. We lean into God, and God leans into us to do what we need to do. That is why ‘The river is chilly and cold, chills the body but not the soul.’ ”

Author and abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote that he had not really prayed until he prayed with his legs and trusted God enough to walk to freedom. Jordan-Simpson called this “prayer in motion.”

Abolitionist and freedom fighter Sojourner Truth worked through the courts in New York to get her son Peter back after he had been sold.

“She held God accountable to God’s own character,” Jordan-Simpson said. “She told God, ‘If I had something you needed, I would give it to you. You can make these people do for me, and there will be no peace until you do.’ ”

Jordan-Simpson continued, “Imagine a world turned to God with the spirit of Sojourner Truth. That spirit would stir the waters of the river.”

In his book, Prayers for Dark People, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote prayers for students who were from the rural South. Their parents and grandparents had been enslaved, and he knew these children would understand the language of prayer.

“He knew that they had witnessed their land stolen, lynchings and violence, and he was determined to stand with them in their formative years,” Jordan-Simpson said. “He spoke in the language of prayer so they could understand. He listened to God on their behalf.”

Jordan-Simpson uses a copy of Du Bois’ for her prayers.

“I try to feel what he felt, to wake up to the words,” she said. “I am joined by the Spirit to do something in the world that breaks my heart; to see and feel the book keeps me in my body and keeps me moving to face the tragedies that break my heart.”

The book inspires her during difficult times.

“The book helps me to speak when I feel like quitting,” Jordan-Simpson said. “It keeps me connected to people I am not sure even like me. I am in the river trying to move, and I feel naked.”

She urged the congregation that when they feel discouraged, to remember the people who put “their face to the rising sun,” and worked for a future they would never see. They “prayed in motion,” walking, fighting, moving, struggling.

“Prayer is not a jumble of words. The Spirit will move us so we go and stand with someone. Some of the most profound prayers have no words,” she said. “Amen.”

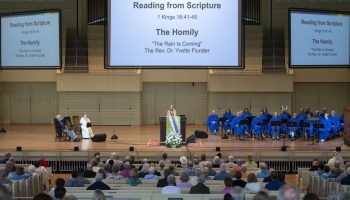

Deacon Ray Defendorf, co-host at the Catholic House of Chautauqua, presided. Linda Thompson Bennett, a member of the Motet Choir, the Chautauqua Choir and the Chautauqua Community Band, read the Scripture. The prelude was “Wedding Hymn,” by Jennifer Higdon, played by members of the Motet Consort: Barbara Hois, flute, Debbie Grohman, clarinet, and Willie LaFavor, piano. The Motet Choir sang “Every Time I Feel The Spirit,” a traditional spiritual arranged by William L. Dawson. Jim Evans served as soloist. The choir was under the direction of Joshua Stafford, director of sacred music and holder of the Jared Jacobsen Chair for the Organist. Nicholas Stigall, organ scholar, played “Partita on Detroit,” by David Hurd, for the postlude. Unless otherwise noted, the morning liturgies are written by Chautauqua’s Interim Senior Pastor, Natalie Hanson. Music is selected and the Sacred Song Service created by Joshua Stafford. For PDFs of the morning liturgies, send an email request to religionintern@chq.org.