“Are Chautauquans afraid of burnt cork?” Written in The Chautauquan Daily on Aug. 6, 1909, the puzzling question captured the reluctance of the Chautauqua public regarding their participation in the annual minstrel show. However apprehensive early Chautauquans were, figures like Arthur E. Bestor (the director of the Chautauqua Institution and later president) stated they were not afraid to “blacken up” for the sake of continuing the show. On the subject of the Daily article, American Studies scholar Elizabeth Lloyd Harvey writes that “community leaders could … (push) the bounds of what they would usually say and do, because they were in blackface.” In short, blackface performances amplified race and class distinctions while offering prominent figures an opportunity for “escapism,” however problematic.

Traditional to 19th-century blackface minstrelsy, “burnt cork” was used by white performers as a costuming effect to darken their faces and physically embody exaggerated caricatures of Black enslaved people on Southern plantations. Blackface minstrelsy dominated as the main source of theatrical entertainment for wealthy, white, male audiences throughout the 19th century. After the Civil War, blackface minstrel shows no longer required theater houses, professional actors, or popular touring companies to be staged. Chautauquans — like many other amateur showrunners — took advantage in the rapid commercialization of the performance.

In lieu of a theatrical staging, 20th-century minstrel shows propagated as street or circus acts for quick monetary gain. Due to these varying forms, the act of putting on “blackface” was now deemed a less-acclaimed artistic practice. Chautauquans could have been reluctant to act in the show for a variety of reasons: one, they were aware that it reproduced harmful, derogatory stereotypes; two, it was simply a class issue. The attitude surrounding minstrel shows changed over time, and darkening one’s skin for the performance could ostensibly devalue one’s social or financial position rather than excel it.

The evolution of the blackface minstrel performance in Chautauqua started in 1882, and the forces of racism and anti-racism clashed often in the community’s early years, with racism often winning. After Chautauquans held their very first Recognition Day in honor of the newly graduated class members of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, there was a need for entertainment to lighten up the formalities of the day. Professor Frank Beard, iconically known during this time for his “chalk-talks” — comedic illustrations artistically performed as Bible lessons — had the idea to organize a “mock commencement” of the Recognition Day.

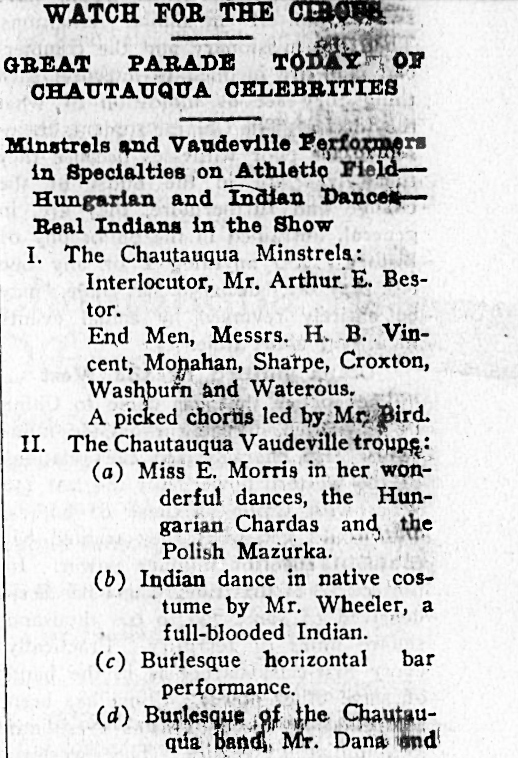

Historian Jesse L. Hurlbut notes in The Story of Chautauqua that the celebration surrounding the annual Recognition Day “finally grew into a ‘mock-commencement’ ceremony organized to make fun of the prominent figures and features of the graduating class.” By the early 1900s, Chautauqua public figure Otto F. Monahan spearheaded the event and it was changed to the “Chautauqua Circus,” an annual gathering organized by what was then the Athletic Club. The circus included acts such as minstrel shows, animal exhibits and vaudeville performances attempting to showcase the “history” and “cultural customs” of Indigenous tribes.

As posted in the Chautauqua Assembly Herald in 1902, figures like Beard even consented to “make an appearance with the minstrels” as the mock commencement evolved. Typically the Chautauqua minstrel performance included an “interlocutor,” and a chorus of “endmen” choreographed in a semi-circle performing a collection of songs and slapstick that made fun of community officials and participants who were willing to wear the “burnt cork.” Black people were the visible punch lines of the parody. Songs like “Mr. Monahan Song’’ emphasized the “tongue-and-cheek” element of the community roast, while the demeaning incorporation of blackface enabled affluent Chautauquans to further distinguish themselves from African Americans and perpetuate derogatory stereotypes about Black people as “loud,” “uneducated,” “poor” and “uncivilized.”

Minstrel shows were indeed violent tactics used to thwart Black progress, and it leaves room for one to ponder on the issue of accountability. Frankly, how might we observe or give voice to issues historically circumvented? These Chautauqua minstrel shows were never listed as official summer events in the Institution’s printed material, and one can speculate as to why that was the case. Perhaps they viewed the annual circus festivities as insignificant? Perhaps there was an understanding that these events were inconsistent with Chautauqua’s image or purpose?

More archival research may shed light on these answers. Either way, I leave you with an irremissible question, and that is: how were Black or even Indigenous community members affected by these annual affairs? What ramifications do these minstrel performances have on our contemporary society and the issues of diversity on the grounds today?

— Iyanna Hamby

Administrative Coordinator, African American Heritage House