Mariia Novoselia

Staff writer

A trip from California to Hawaii can be challenging, especially if the mode of transportation is a raft made of 15,000 plastic bottles.

Marcus Eriksen, co-founder and chief scientist at the 5 Gyres Institute, embarked on a sailing voyage with Captain Charles Moore, who discovered the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, in January 2008. In February that year, he got engaged to Anna Cummins, the other co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute, and met sailor Joel Paschal.

Together, Eriksen said, they decided to make a raft for Eriksen and Paschal to sail from Los Angeles to Hawaii. Soon they chose the date for their departure, Eriksen said – June 1, “no matter what.”

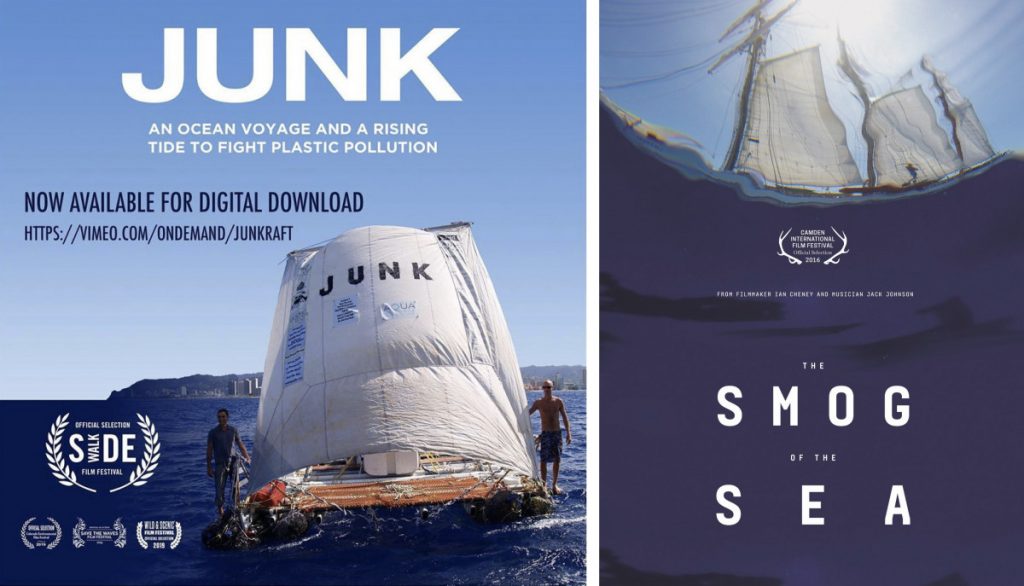

The documentary “Junk Raft” tells the story of Eriksen and Paschal as they completed a 2,600-mile voyage, while providing “commentary on fossil fuels, plastic production and the true cost of plastic pollution,” Eriksen said.

Free with a Traditional Gate Pass, screenings of “Junk Raft” and “The Smog of the Sea” are set for 5 p.m. today in Chautauqua Cinema, with each film running about 30 minutes.

Making the raft out of plastic bottles and an airplane fuselage for its cabin took Eriksen, Cummins and Paschal around two-and-a-half months. Sailing to Hawaii, however, turned out to be a longer process.

“I thought it would take us three or four weeks, (but) it took us three months of drifting at 1.5 miles per hour,” Eriksen said. “I could have walked to Hawaii faster.”

He said the raft didn’t have a motor or a support boat, making the journey “not very safe.”

“If we had had a problem, we could have called the Coast Guard, and they would have requested a ship nearby to try to find us – that’s the best that we could do,” Eriksen said, noting that he and Paschal would take turns sleeping. “There was always someone awake, paying attention to the wind, the waves and the stars to keep us going straight.”

Going in the right direction, Eriksen said, was a big challenge at the beginning of the voyage. Instead of Hawaii, he said, currents were taking the raft to Mexico. In the first three weeks, Eriksen said, he and Paschal did not cross a single line of longitude, and they considered changing the original plan and heading to Ecuador.

“We thought: ‘This is not going to work.’ Then, all of a sudden, one day the winds changed, and the boat turned 90 degrees. We began going west to Hawaii, … and stayed on that path,” Eriksen said.

Paired with “Junk Raft,” “Smog of the Sea” follows Eriksen on a “action-packed star-studded voyage” on a much bigger boat, as he sails through the Sargasso Sea – “from Miami to the Bahamas, from the Bahamas to Bermuda, from Bermuda to New York City,” he said.

Other voyagers in the film include singer-songwriter Jack Johnson — who wrote the score for the short film — and professional surfers Keith and Dan Malloy.

The goal of the film, Eriksen said, was to “bring attention to the plastic pollution issue” and accelerate the progress of solving it.

What surprised several people from the ship, Eriksen said, was that not all plastic in the ocean is in large pieces; some even wondered where it was at all.

“We kept on dragging a fine mesh net behind the boat, (and) every time we pulled it up, there was a teaspoon of microplastics,” Eriksen said, noting that the challenge is recognizing “the ubiquity and the vast number of (plastic) particles.”

He said he hopes both films help viewers find different ways to consider environmental issues through art. Films, he said, like other types of art, can do what science cannot.

“Science by itself doesn’t reach everyone, and art by itself doesn’t reach everyone,” Eriksen said. “If you combine art and science, you get a much larger audience, and that’s the goal. It’s also a way to invite other people to get involved in what seems like a very hard story to get involved in – it’s depressing at times, but you can give people a chance to use art to express their frustrations, their ideas, their opinions. Art does that, whereas science does not.”

A panel discussion with Katie Dougherty, executive director of “Washed Ashore – Art to Save the Sea,” and Chautauquan Subagh Singh Khalsa, who embarked on his own journey down rivers across the United States, will follow the double feature.

A year after Hurricane Katrina swept through the southern United States in 2005, Khalsa interrupted a bike ride on a spot that overlooked Lake Erie and Chautauqua Lake. The former, he said, is part of the Great Lakes watershed, while the latter is the beginning of the Mississippi watershed.

There, he said he realized that everything that goes into Chautauqua Lake ends up in New Orleans and the Gulf of Mexico. Together with news of the hurricane and estimates of damage it caused, he decided to embark on a kayak journey from Chautauqua Lake to Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

“My first thought was: ‘I want to do that trip.’ My second thought was: ‘I don’t think my wife wants me to do that trip.’ My third thought was: ‘If I raise money, then I can justify doing the trip,’ ” Khalsa said.

Even though the amount raised was not enormous, he said he donated it equally between Chautauqua Watershed Conservancy and Habitat for Humanity in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Over 15 years after the trip, Khalsa described the current state of the environment as horrendous.

“We are on a wholesale binge to destroy as much as we can, and we’re all part of it,” he said.

Everyone, however, can also be part of the solution, he said. Khalsa suggested advocating for positive environmental change through targeted stock purchases, voting, and reducing personal carbon footprints.

He said he hopes the two movies and the discussion that follow will help Chautauquans realize why everyone, regardless of where they live, affects and is affected by the watershed, as well as why prompt response is necessary.

“We’re all downstream from somebody, and we’re all upstream from somebody – the junk we put into Chautauqua Lake … winds up in the Gulf of Mexico, but the rain that comes down on our heads is acidified by the people in the Midwest who are creating atmospheric changes and so, we’re downstream from them,” he said. “Our grandchildren will suffer if we don’t get it together really fast.”