Kaitlyn Finchler

Staff writer

In a time when free speech is under threat across the globe, not everyone has the luxury to remain silent — and they face persecution as a result. Some countries arrest people for simply documenting a public event or speaking out of turn against their government.

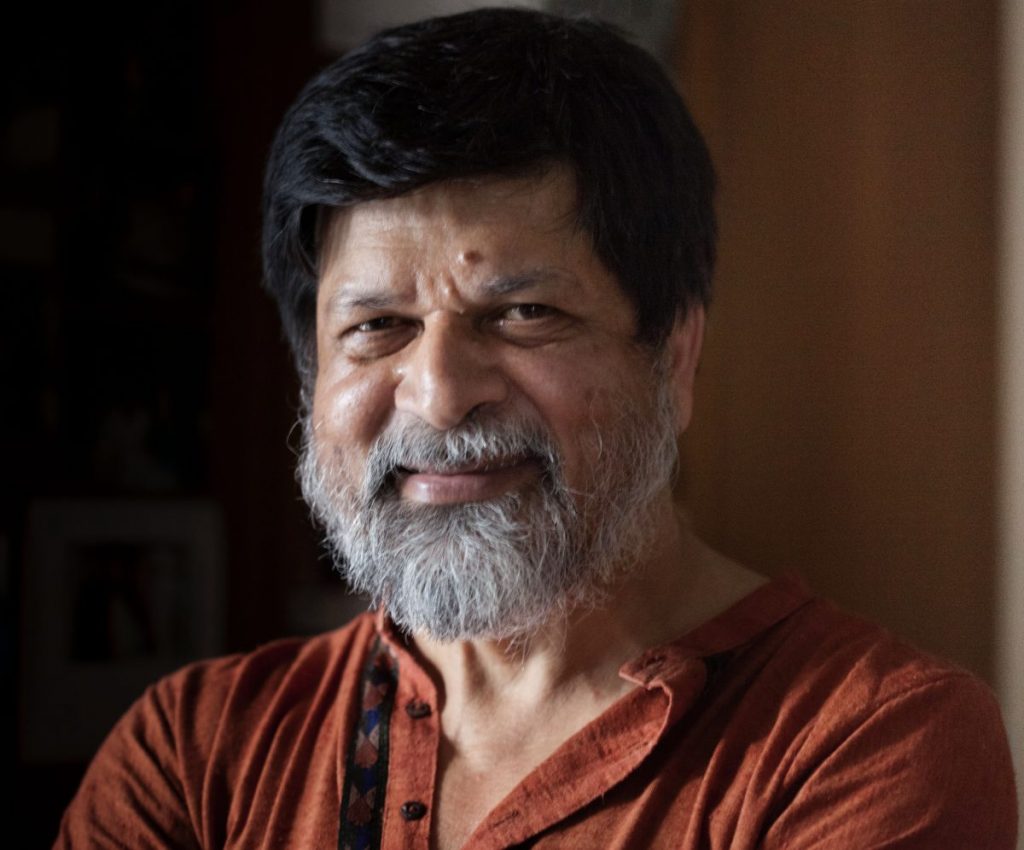

Shahidul Alam, National Geographic explorer-at-large, is a photographer, writer, curator and human rights activist from Dhaka, Bangladesh. After obtaining a doctorate degree in chemistry, Alam switched to photography in 1983 and has been documenting the struggle for democracy in Bangladesh ever since.

He will give his lecture at 10:45 a.m. today in the Amphitheater for the Week Nine theme, “The Global South: Expanding the Scope of Geopolitical Understanding.”

“I am very concerned about the fact that migrants in my country, and probably elsewhere, are treated abysmally by the very people who profit from them,” Alam said.

Another concern is the hypocrisy and stereotypical representation of developing countries by Western development agencies and media. To combat this, he co-founded the photo agency Majority World in 2004 as a platform for local storytellers to tell their stories.

“Not only to talk about the reality of our situation, but also the cultural richness, the nuances and the human fabric around it,” Alam said. “While we were doing that, we also began to question our own position within the media space.”

As a middle-class male photographer, he was aware of, and wanted to break down, the power dynamic he felt with the people he photographed.

Alam moved to London after living in Bangladesh for the majority of his life, but had to move back to Dhaka for his parents — something he struggled with a lot.

In his earlier work, Alam said he was censored and although the government encouraged artists, they didn’t want the artists to be political.

“I made a conscious decision that in my subsequent work, I would not allow the politics of my work to be separate from the aesthetics,” he said.

He said he wants Chautauquans to think about the concept of “otherness,” which he believes is the root of most problems. There are a lot of unspoken rules, he said, across the globe that are applied to countries differently based on how they’re perceived in the Western world.

“We are at a very difficult time in the world today,” Alam said. “We are in a position to be able to change it, but that change will only happen if each one of us plays our role. I hope, through my talk, I’ll be able to get some people to become more correct.”

The concept of a “Global South” is difficult to define, he said, because there’s no singular definition in geography, politics or economics to understand it without a broad context.

“Entities like the United Nations, which purport to be the global champions of global values, very rarely apply that lens to themselves,” Alam said. “The old laws of colonialism and imperialism (in) different forms (are) sometimes much more sophisticated.”

Rather than “Global South,” Alam said he prefers the term “majority world,” to remind the West, which “talks so much about freedom,” that the eastern side of the globe does in fact make up most of the world.

“When (Western leaders) take on that mantle of becoming global saviors, I want to question whether they have the liberty in doing so (if) they actually do it through our lens,” he said.

The core principles and power structure of journalism exemplifies the world is uneven, Alam said. For a subject to rightly question if a storyteller or journalist can understand them indicates a history of misreprentation on the part of the West.

“We can tell more nuanced stories,” Alam said. “We can tell stories from a position of trust, stories which are more in-depth, culturally sensitive and perhaps richer and able to encompass broader emotions of human value.”

On Aug. 5, 2018, Alam was taken from his home shortly after giving an interview to Al Jazeera and posting live videos on Facebook that criticized the government’s violent response to the 2018 Bangladesh road safety protests.

“Security people came into the flat, blindfolded me and took me away,” Alam said. “I was fortunate that I was put in remand, a state-sponsored project, and I spent seven days in jail.”

Bangladesh, he said, is a very repressive state and turned down his bail six times, and the case has continued since. Every month since his release, he has to appear in court. His court date in August is today, which he suspects was “deliberately done” by the Bangladesh government, since he will be speaking in the Amp and not able to appear in court.

“Constitutionally, the case has to be dropped,” Alam said. “But the government’s judiciary has decided not to do that. … Either I have to skip going to Chautauqua or risk being absent in court.”

This would be Alam’s “first offense,” he said, as he actually hasn’t committed a crime thus far, but failing to appear in court would qualify as one.

“If I’m not there on the 22nd, I will have actually broken the law,” he said. “It might well be this is a trap they’ve set to put me back in jail.”

Alam has been charged with spreading false information and making provocative statements; the government, he said, has no evidence to support that claim, and he wants to use his lecture to show international solidarity.

“We live in a very polarized world,” he said. “It is up to us as global citizens to actively bring down those barriers and each of us has a role to play. I would like to provoke and inspire people to do the same.”