Kaitlyn Finchler

Staff writer

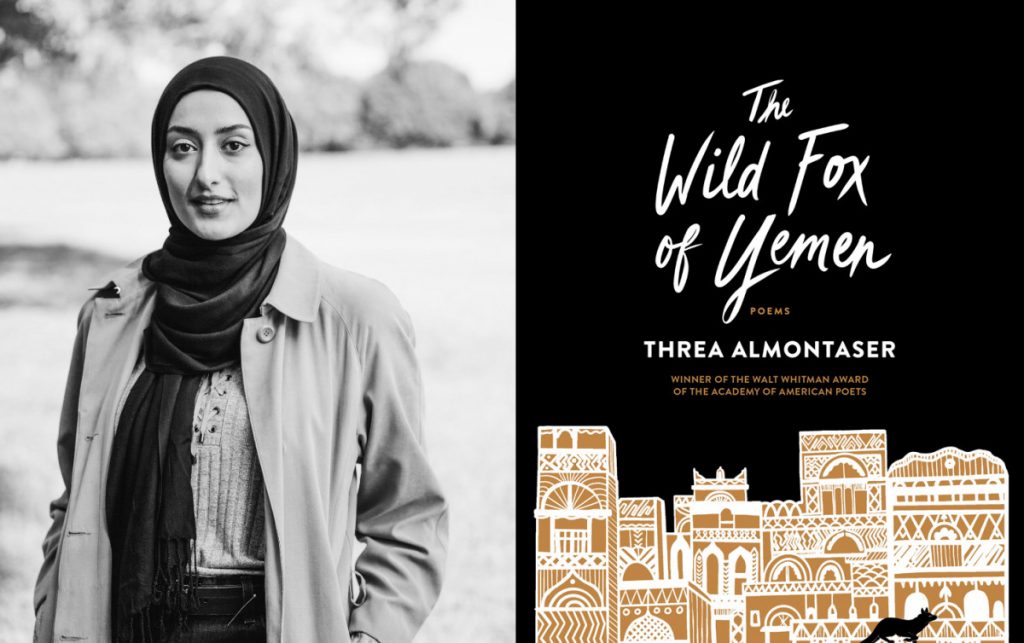

Translated poetry, when done well and with good intent, can be evocative and inspiring. When done poorly, it can lead to cultural appropriation and misguided perceptions. In her collection The Wild Fox of Yemen, poet and translator Threa Almontaser notes that “just one percent of Arab and Asian translation into English has been achieved thus far.”

For example, she could only find one piece from Yemen’s most celebrated poet, Abdullah Al-Baradouni, translated and readily available online. In setting out to translate more of his poetry, Almontaser found that her own writing was fueled in the process.

Almontaser will share some of this writing when she delivers the final Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle presentation of the summer, on The Wild Fox of Yemen, at 3:30 p.m. today in the Hall of Philosophy.

“There’s a distinct attempt in my work to articulate the ‘betweenness’ of realms through narrations that blur the lines between memories, half-truth, desires and history,” she said. “I attempt to write about experiences that I feel have been underrepresented in modern literature.”

The book is a 2021 recipient of the Maya Angelou Book Award and the Brooklyn Public Library Literary Prize, as well as a finalist for the 2022 NAACP Image Award for Poetry and Kate Tufts Poetry Award. Additionally, Almontaser has been the recipient of the Walt Whitman Award of the Academy of American Poets.

Sony Ton-Aime, the Michael I. Rudell Director of Literary Arts, said the book forces readers to possibly become “uncomfortable,” rather than “center themselves,” when talking about the relationship between the Global South and Western world.

“Specifically, the vast majority of people in the West might not know Arabic, so it asks you to do some work,” he said. “If you are really interested in the Global South, you have to do some work to get to know what the Global South is.”

Almontaser’s poetry is a form of documentation and provocation, she said, to serve as witness. She said wants others in her community to read and, in her work, recognize things they may be too afraid to say out loud. Eventually, she’d like to help others find their own voices of poetry and witness.

“I’d like to start an initiative to support documentary poetry — reported poetry based on interviews or oral histories, and in a sense, expanding that global scope of stories told about us,” she said.

The Wild Fox of Yemen explores translation as a form of self-knowledge and survival. Portrayed as a love letter to the country and people of Yemen, the portrait of young Muslim womanhood examines the pre- and post-9/11 world, and what it means to forge an identity amid the limits of American imagination.

“I sometimes write in Arabic to make the reader feel as thrown off, unsettled, separated and misplaced as the speaker seeking refuge did,” Almontaser said. “In this way — even though I write poetry mostly in English — it feels like an observation of the Arabic language and identity.”

CLSC Octagon Manager Stephine Hunt said Chautauqua Literary Arts aims include a poetry collection at least once per season, and The Wild Fox of Yemen’s use of Arabic strategically challenges Western norms.

“(Almontaser) is purposefully writing against our assumption that any book that exists should be easily consumable (and) easily accessible,” Hunt said. “People should be able to pick it up and sync with it, in some capacity. But the way she’s complicating it is strictly cultural.”

This is done, Hunt said, through pieces of Almontaser’s Yemeni home and culture people can’t “easily Google.”

“(The book) is clearly written for an audience that’s from that culture,” she said. “In some cases, that inaccessibility is purposeful to say, ‘You shouldn’t be able to assume that I’m going to give you all of the answers (or) give you the secrets (and) histories of our culture.’ ”

Being Yemeni and speaking Arabic, Almontaser said, helped her recognize and sense more ideas or feelings that exist in Arabic but not English, and vice versa.

“I proudly claim my heritage by making visible the fact I’m a Yemeni-American writer, because I’ve never found contemporary literature written by my people, especially of this generation,” she said.

For a culture so rich and ancient to be hidden away, she said, is sad to know. The publication of The Wild Fox of Yemen lets her join the ranks of — or perhaps be one of the first — literature written by young Yemenis and Yemeni-Americans.

As the oldest child in her immigrant family, Almontaser — who currently teaches English to immigrants and refugees in her area — said she was a designated translator growing up. In doing so, she experienced language barriers and fragmented interactions first-hand.

“My upbringing plays a big factor in wanting to teach English,” she said, “to build more solid relationships, break misconceptions and barriers, and help bring out the impactful narratives and voices of the ESL learner.”

When faced with a sense of “social powerlessness,” Almontaser said mixing poetry with politics is crucial.

“If the language we hear on television broadcasts no longer stirs us to do anything more than tweet our dismay, poetry can express something new — or something old in a new way — and this can energize us to take action,” she said.