Howard Halle

guest critic

Rendering the human form is as old as human expression itself, though its centrality in art has waxed and waned over time, especially during the 20th century, when whole new modes of visual thinking — abstraction chief among them — were introduced. Which isn’t to say that figurative subjects disappeared: They certainly didn’t, though artists were obliged to fit them into a theoretical framework defining art as a chain of radical innovations built one on top of the next — a heroic pushing of the envelope, so to speak, that became the story modernism told itself about itself.

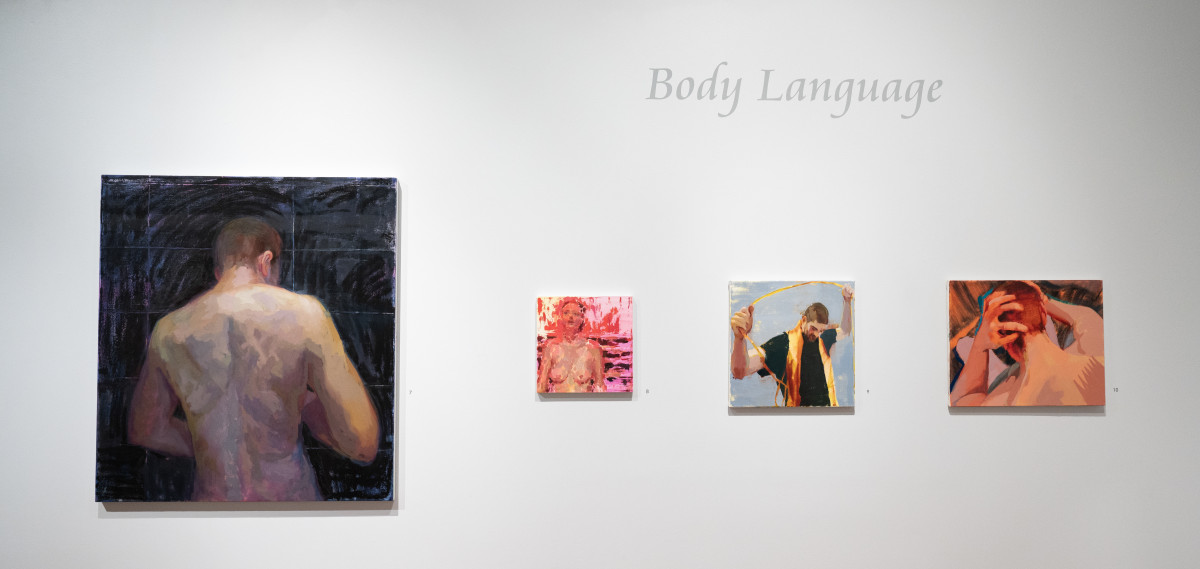

Like so many disruptions by late capitalism, though, the notion of an art-historical narrative based on stylistic progress has been left for dead. What remains is an “everything everywhere all at once” eclecticism that includes the resurgence of figuration, albeit in a mix-and-match format composited out of 100 years of change. If nothing else, the work of the six artists currently on view in the Judy Barie-curated “Body Language” at the Strohl Art Center’s Gallo Family Gallery represents a microcosm of those developments. There’s more to the show than that, of course, as its participants take on delivering the “desires, moods, interpretations, and wonder that each of us possess,” according to the gallery’s statement. Yet the exhibition title also alludes to a broader redefinition of the human presence in art, from a supposedly neutral construct that reflected a largely white, male point of view to a concrete manifestation of identity politics — a transformation, in other words, of “figure” into “body.” Though a seemingly small semantic distinction, the latter, borrowed from the language of feminism and social justice movements like Black Lives Matter, has been important to revising a tradition that previously sidelined women and people of color. Whether directly or indirectly, the works here echo that change.

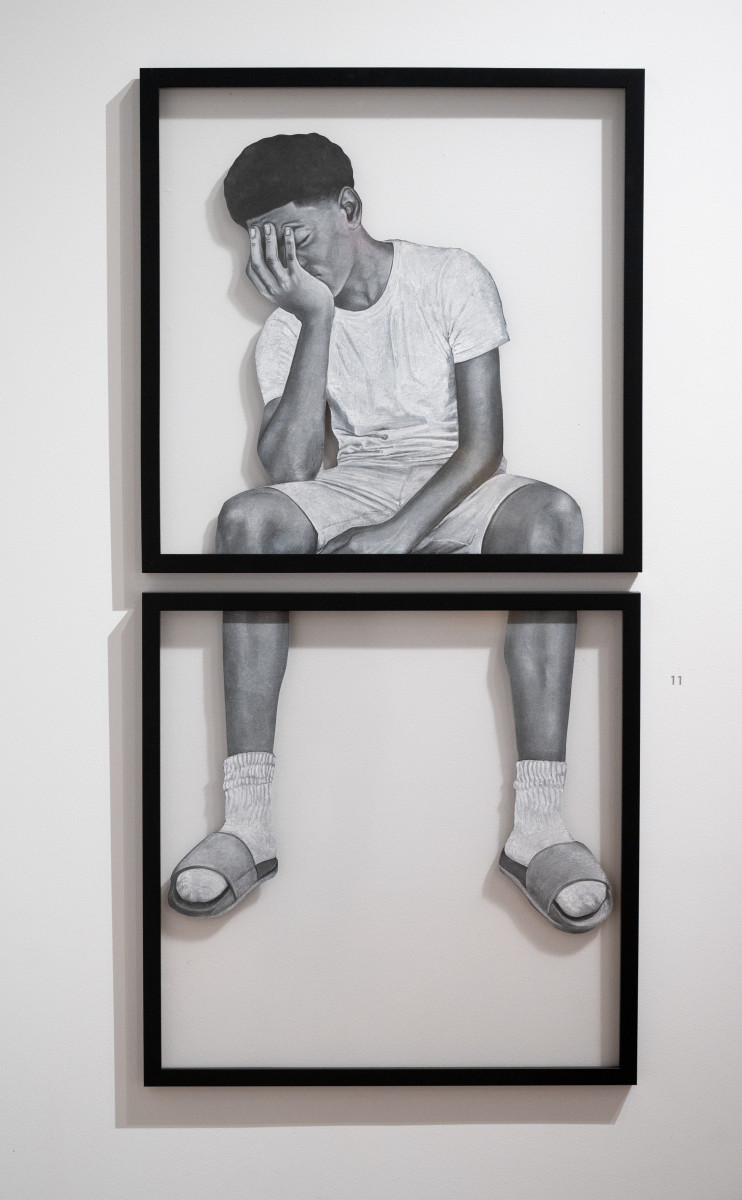

Among most head-on in this respect is a series of grisaille studies by Miami artist Chris Friday. Rendered in chalk and acrylic on black paper, Friday’s images picture ordinary African Americans isolated as full-length physical cut-outs with background details elided, some measuring larger than life-size. Two, hung across the gallery from each other, evoke a sort of yin-yang of feeling: “Lemon Pepper Steppers” (2023) depicts a pair of women dressed in church-going finery, who are, in fact, the same person, dancing exuberantly with her mirrored self. “In/Visible Men/d: Untitled, Bri’on” (2021) — a title that clearly references Ralph Ellison’s 1953 classic, Invisible Man — shows a youth posed as if leaning against a wall with one hand stuffed in his jeans, while his face is buried in the other. Together, the two pieces swing back and forth between celebration and despair, reclaiming an emotional space that Black bodies, as Friday puts it, are ordinarily denied.

In a similar vein, Pittsburgh-based Francis Crisafio’s “Hold up in the Hood” (2009) comprises a set of photographs of Black children concealing themselves behind masks made of images snipped from magazines. One child, for example, hides behind an ad featuring a white woman modeling a watch; another peers out through the face of an owl; still another does the same with an adult Black man. Part of a larger project involving kids from a local elementary school, “Hold up in the Hood” is a shrewd comment on the idea of demography as destiny.

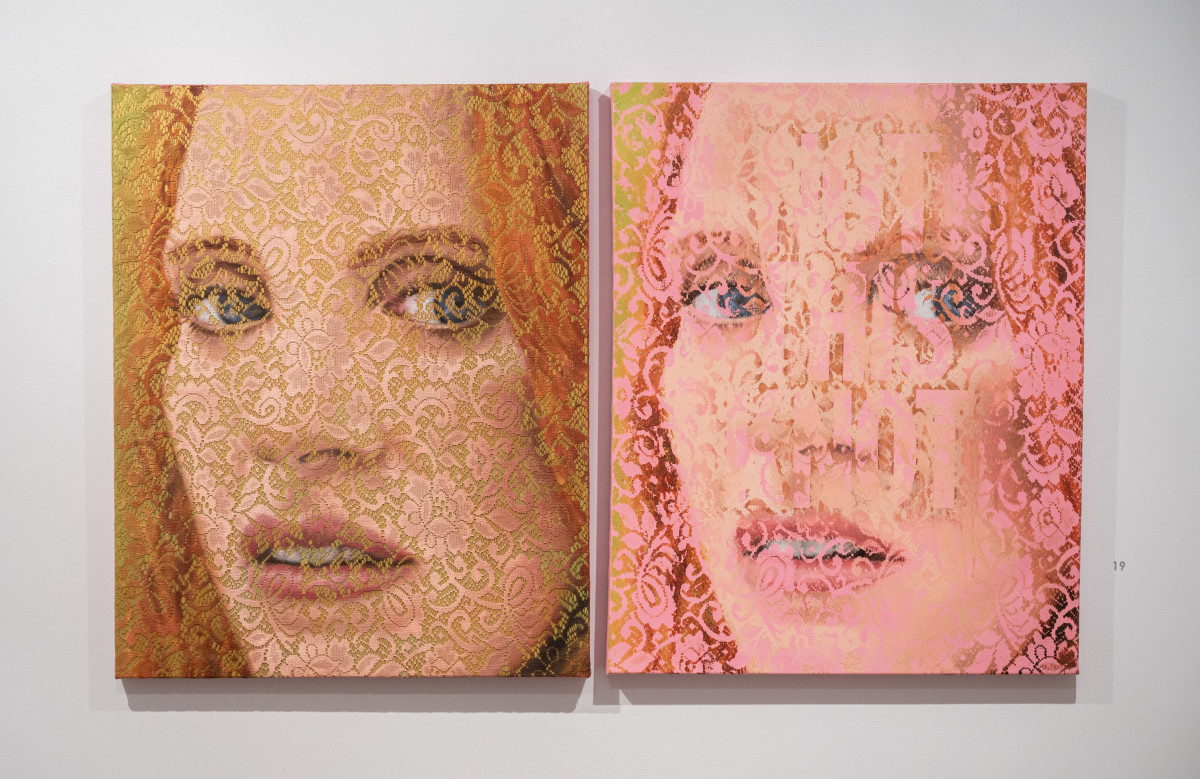

Hailing from Richmond, Virginia, Elizabeth Coffey offers mixed-media portrait diptychs of women that are apparently borrowed from archival or media sources. Painted in oil and acrylic on pieces of lace curtain layered atop canvas, the images allude to the diversity of women’s work, both in the domestic sphere and in the labor force, which include traditional roles associated with weaving and other textile crafts, as Coffey’s use of lace suggests.

Other artists in the show appear to be less concerned with gender and race and more focused on sentiment, though to varying degrees with both. Bay Area ceramicist Beverly Mayeri presents uncanny figurative reliefs and sculptures in painted clay. Mayeri meditates on suppressed anxieties in pieces such as “Undecided” (2010), a bust of a woman wearing an expression of doubt that likely relates to the profile of the man limned over her heart; incised with a brick pattern, she’s literally walled herself off from attachment. An infant pops out of the eponymous vessel in “Baby Teapot” (2018) looking very worried, indeed — a psychological projection, if there ever was one, of the travails of motherhood. Meanwhile, “All American” (2022) allegorizes the country’s racial makeup as bands of black, brown, yellow and white wrapping around the face of a bewildered man.

Born in Japan, Kensuke Yamada fashions childlike figures in stoneware, which, like the work of Yoshitomo Nara, are rooted in anime; one of them, “Head 3” (2022), seems oddly nonchalant about the shards of Chinese porcelain buried in its head and neck like razor blades.

Finally, Rachel Rickert’s paintings constitute the most personal and subjective contributions to the show, related as they are to her own life. Three are nude self-portraits, in which she’s seen in the shower or bedroom, while another three feature a man (Rickert’s significant other, perhaps) in various prosaic scenes, including one behind-the-head view after he gets his haircut (“Shearing” 2018).

Working in a wide vocabulary of modes ranging from the political to the personal, the artists here address the exhibition’s premise in diverse ways. But whatever the syntax, they demonstrate that when it comes to talking, the body speaks volumes.

Former Editor-At-Large at Time Out New York, Howard Halle writes regular exhibition reviews, including for Art & Object.