Review by Rebecca J. Ritzel

Some 160 years ago, an Irish actor and playwright with a French stage name traveled to America and was appalled by the reality of slavery.

So, he wrote a play about it.

It was called The Octoroon, and the heroine was the young daughter of a Louisiana landowner who is auctioned off when the plantation goes under because she is one-eighth black and seven-eighths white, hence the name chosen by playwright Dion Boucicault, The Octoroon.

MacArthur genius playwright Branden Jacobs-Jenkins is a big fan of Boucicault, whose most famous play is probably The London Assurance. So he paid homage his 19th-century predecessor by drastically reworking the Octoroon script, with both himself — and Boucicault — featured as characters. The resulting play is a little hard to follow, but The New York Times theater critics recently named it one of the top 25 plays of the past 25 years. And since An Octoroon is receiving a very entertaining production at Chautauqua Theater Company through July 8, now is a very good time to see it.

The play will not be for everyone on Chautauqua Institution grounds; Saturday’s opening performance was undersold, and a number of patrons walked out, including two irate ladies who made a noisy exit during the prologue, when the actors playing the two playwrights let loose a string of expletives/F-bombs.

They should have stayed. The cursing (mostly) stops once the curtain opens, and audiences are transported back to antebellum Louisiana, courtesy of Lee Savage’s surrealist set. Savage is a Chautauqua success story, a still young(ish) designer who began working with CTC during the Ethan McSweeny/Vivienne Benesch years and has gone on to work with opera and theater companies around the world. For An Octoroon, he created an elaborate Rococo picture frame to hang at the rear of the stage, a raised platform that can serve as both a boat dock and a veranda, and puffy cotton-ball clouds that double as light fixtures.

High-quality projections that resemble stills from “Gone With The Wind” fill the picture frame throughout the show. What audiences are watching is not the actual old South, but a tongue-in-cheek commentary on it, with dialogue that bounces artfully between contemporary slang and the 19th-century vernacular.

“So you know Chris and Darnell?” a slave named Minnie (Nija Okoro) asks her fellow forced laborer Dido (Janet Fiki), as she sweeps cotton balls on the veranda once Act I opens.

“Yeeuh. How you know Chris and Darnell?” Dido returns.

“Oh, you know, Chris was messin’ with Trisha over in the sugar mill for a l’il bit. … but she dumped him because, you know, she couldn’t deal with the long-distance.”

Okoro gets lots of laughs. The banter she shares with Fiki is a fantastic mash-up of teenagers-at-the-mall slang and Southern colloquialisms, and a highlight of the show. Okoro is one of three out-of-town professionals hired to round- up CTC Conservatory actors, and she’s terrific as the new house “slave” (the N-word is casually dropped on several occasions in this show) who has just been transferred from the cotton fields to Terrebonne’s main residence.

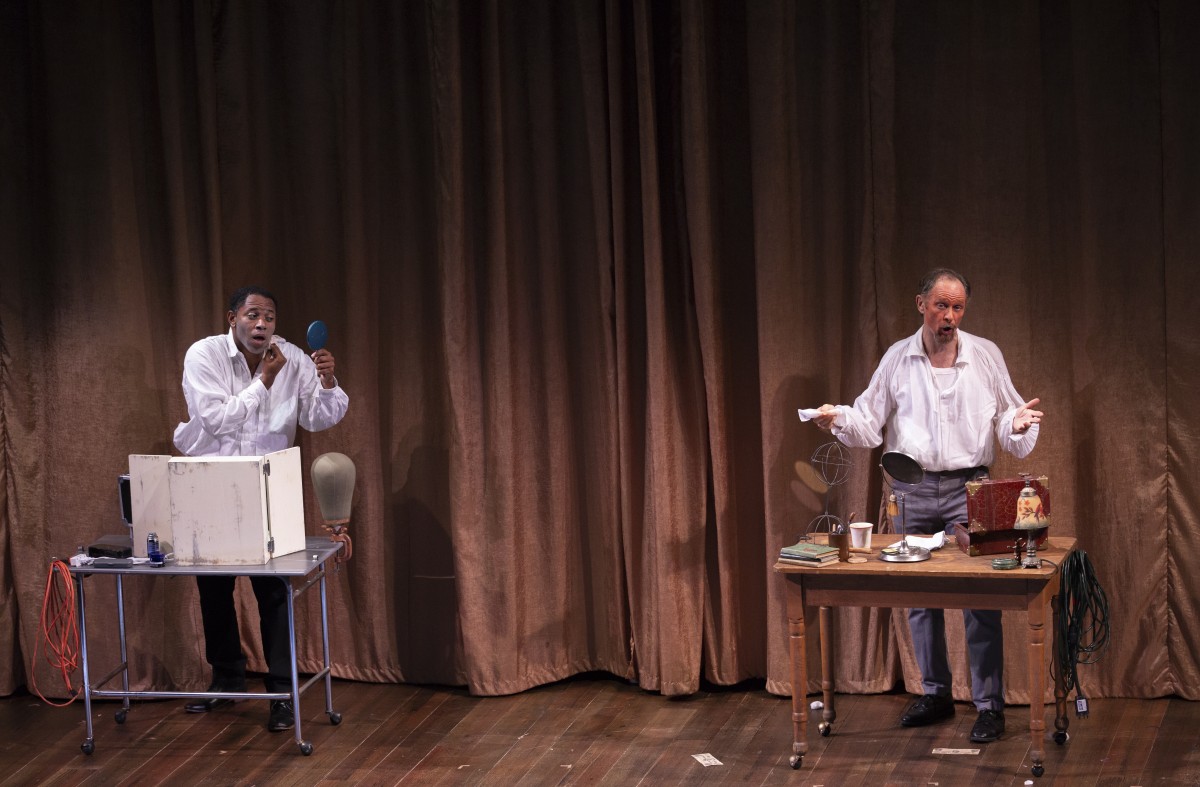

Visiting Director Giovanna Sardelli and CTC Artistic Director Andrew Borba were smart to farm out the lead roles for An Octoroon. Los Angeles-based actor Larry Powell plays the triple role of the playwright, the hero George and the evil rival plantation owner M’Closky. Powell is a phenomenal physical comedian, and Brett Rickaby is equally funny as both his foil Boucicault, the auctioneer and Wahnotee, a purposely cartoonish Native American, or “Injun,” as he’s referred to onstage.

Of the CTC conservatory actors, the standout is Keshav Moodliar, a London native now training at Juilliard. He adopts a different accent and posture for each of his three roles, so someone please, please get the poor kid a chiropractor (and more starring roles) when the run of An Octoroon is through.

Costume changes usually make it easy to distinguish between characters, but the metanarrative aspects of the show — when the curtain is closed and the two playwrights commentate on the action — can be confusing. The commentary dialogue also drags just a bit, and could be delivered to with more clarity.

The sound design (by Vincent Olivieri) is quite elaborate: very cool when it works and distracting when it doesn’t. During the opening monologue, Powell gets down to Childish Gambino’s “This is America,” which is blasted throughout the house. Stephen Foster tunes underscore the main story action, as well as occasional old-timey film score music that is intended to parody Clark Gable classics. Those surges of strings could be louder.

Sardelli also diverged from the stage directions by placing special emphasis on the show-ending singalong. It’s a sweet moment to have the actors onstage instead of off, but Jacobs-Jenkins’ intent in An Octoroon is to reimagine what was originally a very sappy show. Having the cast croon spirituals by candlelight is an odd choice for the finale. Still, this is Chautauqua, and if CTC is asking audiences to put up with F-bombs, perhaps it is appropriate to treat those who make it through to a hymn sing at show’s end.

Rebecca J. Ritzel is a Washington, D.C.-based arts journalist who contributes to City Paper, Washingtonian and The Washington Post. She holds a master’s degree in arts journalism from Syracuse University.