His resume, too long to list in full, stretches all the way from before the John F. Kennedy administration to the present day.

As the White House press secretary for President Lyndon B. Johnson, he managed media relations in one of the most politically fraught times in American history.

And as a journalist, he led Newsday from 1967 to 1970 as its publisher, afterwards working as senior correspondent for “CBS Reports.”

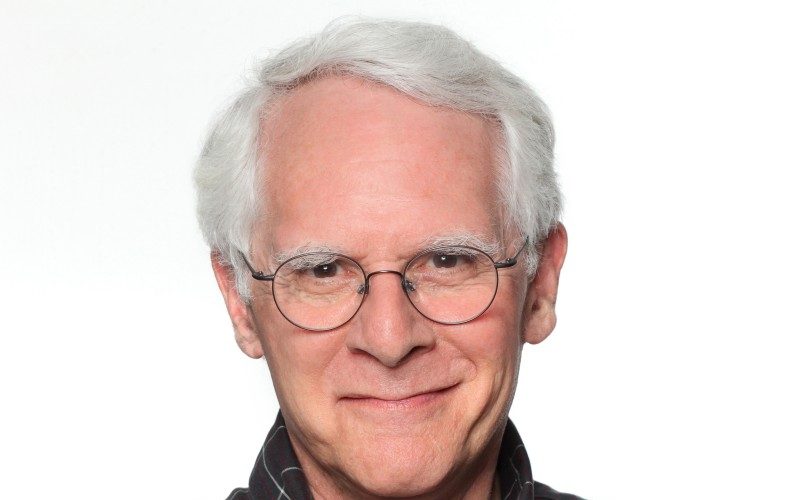

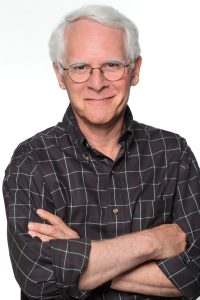

At 2 p.m. Monday, August 12 in the Hall of Philosophy, acclaimed broadcaster Bill Moyers will kick off Week Eight’s interfaith lecture series, “The Power of Soft Power,” with his lecture, “The Other Face of Power.”

One of the key ways Moyers has wielded soft power — defined as the power to attract, rather than coerce — is through his journalism.

“The third pillar of American democracy, an independent press, is under sustained attack, and the channels of information are choked,” Moyers said in his keynote address at the 2007 National Conference for Media Reform. “A few huge corporations now dominate the media landscape in America. Almost all the networks carried by most major cable systems are owned by one of the major media common conglomerates.”

According to Moyers, the few elites in control of the modern media landscape have the power to determine “what ordinary people do not see or hear.”

Moyers began his career in journalism at age 16, when he went to work at a daily newspaper in Marshall, Texas, as a cub reporter.

It was while working at The Marshall News Messenger that Moyers said he got his “big break,” according to an essay published on

TomDispatch.com.

Moyers said that, while most of the journalists at his paper were out on vacation or sick, he was assigned to report on what came to be known as “ ‘the housewives’ rebellion.”

“Fifteen women in my hometown decided not to pay the Social Security withholding tax for their domestic workers,” he wrote. “Those housewives were white, their housekeepers black. Because they tended to earn lower wages, accumulate less savings, and be stuck in those jobs all their lives, Social Security was their only insurance against poverty in old age. Yet their plight did not move their employers.”

Ever since reporting on that story, which was eventually picked up by the Associated Press, Moyers wrote, “I was hooked, and in one way or another I’ve continued to engage the issues of money and power, equality and democracy over a lifetime spent at the intersection between politics and journalism.”

After that story, Moyers worked as a summer intern for Johnson, then a senator, eventually becoming his press secretary and chief of staff after Kennedy was assassinated.

“But though he was in politics, he was never entirely of politics,” journalist Neal Gabler wrote of Moyers in a 2009 article in the Los Angeles Times. “One cannot understand Moyers without understanding his theological training and his moral conviction. His mission has always been to make things better, not louder.”

After Moyers left the White House to continue his career in journalism, Gabler wrote that “(he) has always sought the most interesting thinkers, people who would never otherwise be on television, and then discussed their ideas in search of timeless truths.”

“In a world of certainty that forecloses investigation, Moyers has curiosity,” Gabler wrote. “In a world of glibness and superficiality, he has a rare temerity of mind. In a world of ego and bombast, he has always been modest and self-effacing. He not only gives a forum to unusual thinkers, he is truly, visibly, interested in what they have to say and in who they are because he believes that their ideas really matter.”