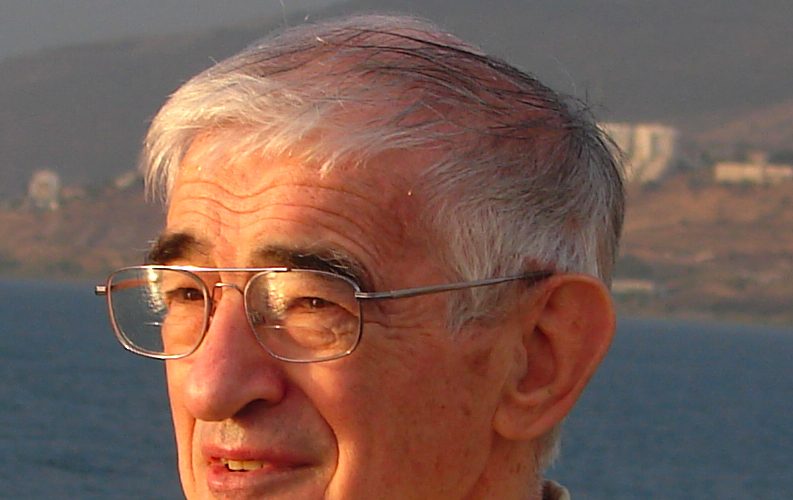

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton thinks the United States has been given an incredible opportunity.

“We can show the world that the world can live in peace,” said Sutton, bishop of the Episcopal Diocese in Maryland, and director of the Washington National Cathedral’s Center for Prayer and Pilgrimage. “The world is coming to our shores. The world is here, in the United States. I want people to be left with excitement and hope at that fact.”

At 2 p.m. Wednesday, August 21 in the Hall of Philosophy, Sutton will declare that “The Dream Still Lives: 50 Years after Martin Luther King, Jr.” as a continuation of the Week Nine interfaith lecture series, “Exploring Race, Religion, and Culture.”

“I’m reflecting on roughly 50 years after the death of Martin Luther King Jr.,” Sutton said. “I’m really asking the question, ‘Are we where we have expected us to be, 50 years ago?’ If you ask most Americans that question, the answer would really be sobering.”

According to Sutton, in some areas there have actually been significant improvements to race relations in the United States.

“By some measures, we are better off — certainly in racial justice,” he said, “and especially in terms of the attitudes of white persons towards black persons. They’ve greatly improved as compared to 50 years ago. We don’t have separate bathrooms, restaurants, that kind of thing.”

Still, Sutton said that it doesn’t feel like “we as a nation are closer to being a more racially harmonious society.”

“In 1968, white supremacy, in an act of gun violence, shot a person of color because that person could not agree with his solution of a racially harmonious country,” he said. “What are we lamenting today? Still, white nationalist groups are shooting people of color, because they reject the vision of a racially diverse, multicultural society.”

One of the things that gives Sutton hope when confronted with that outlook is the plasticity of the U.S. Constitution.

“We have a system that can correct itself,” he said. “We can amend the Constitution. We have a system of justice and laws. In the main, what gives me hope is that we keep referring back to the ideals of equality and justice for all.”

Sutton’s advice for political leaders is simple: They ought to say less.

“Maybe they need to be more silent and reflective, rather than be reactive and just say whatever’s on their mind,” he said. “That moment of reflection — as a nation, we as a people can practice this.”