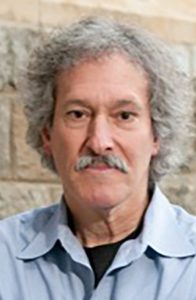

Lisa Sharon Harper’s work didn’t shift during the Black Lives Matter movement — she said this is a moment she was made for.

“The kind of work I do helped to create this moment,” Harper said. “What the movement did is it called out the truth in the face of a spiritual lie. We’ve been waiting for this.”

Harper, founder and president of Freedom Road, will speak on evangelicalism at 2 p.m. EDT Friday, July 24, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform for Week Four’s Interfaith Friday.

The way that we imagine how we should live together in the world is deeply impacted by our faith and how we understand it,” she said. “The two go hand-in-hand, whether we choose to acknowledge it or not.”

Since the 2016 presidential election, Harper said the nation has been in a state of devastating division. What people are learning from it, she said, is that “faith matters.” Faith shapes one’s worldview, which in turn, shapes their politics.

“The way that we imagine how we should live together in the world is deeply impacted by our faith and how we understand it,” she said. “The two go hand-in-hand, whether we choose to acknowledge it or not.”

Harper’s worldview is shaped by her evangelical understanding of the Gospel, a view she will expand on in her Interfaith Friday presentation. Her journey to finding her faith was a long one. It would challenge her relationships, her past, her sense of belonging; but the challenges would bring her to an “life-altering realization” — the “good news of the Gospel” was handed down to her by white people who bore no actual relationship to the scripture they were sharing.

Finally, she said, she found her place in the narrative.

“The text I so deeply believe in actually comes from a social location that is closer to my own than anyone who taught me about it — much closer to that of George Floyd than that of Calvin or Luther,” Harper said.

Harper’s strengthened relationship with religion following her realization changed her life “permanently and for the better,” but several experiences have since disputed the “white evangelical narrative” — particularly in her understanding of Shalom, which she considers to be God’s vision of the world he created.

“Shalom is exploring how God envisions we should be relating to one another,” she said. “It’s how we should be relating to the rest of the creation — the Earth, other animals. It’s how God envisions we should relate to money and how God envisions we should relate to God.”

Shalom, to Harper, is grounded in the book of Genesis, her “founding narrative.” Harper believes Genesis was written by oppressed, enslaved people, and if that’s the context, she doubts the book’s sole purpose was to prove how long it took to make the world. In her eyes, the story is about power, not creation.

“They are writing about how power should be yielded in this world, how we should be relating with each other, about ethics and about the core of Shalom,” Harper said. “That reoriented everything for me, which will be a key part of my talk.”

To share her worldview worldwide, Harper founded Freedom Road, a consulting group, in 2017. Through training, coaching, forums and pilgrimages, Harper said Freedom Road’s mission is to “build a more just world.”

“We help people who are doing justice to do it more justly,” she said. “The major way we do that is by emphasizing the power of story and narrative. We really do believe narrative shapes everything. My story is only one example of that.”

Having to reevaluate and shift a worldview is “literally pain-filled,” Harper said, but creating change in the “right direction” is worth the discomfort it carries.

“There is so much pain in the world because of our divisions, so if the work I have done to understand Shalom helps the church become Shalom-seekers, well, that’s a life well spent,” Harper said.

This program is made possible by “The Lincoln Ethics Series,” funded by the David and Joan Lincoln Family Fund for Applied Ethics and the Thomas and Shirley Musgrave Woolaway Fund.