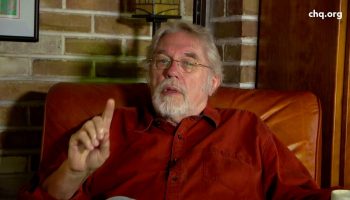

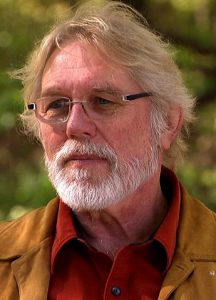

In 1988, when Kent Nerburn started working on the Red Lake Reservation in northern Minnesota, home to the Ojibwe people, he saw the job as a way to support his career as an artist.

“It was a chance to work, (and) I needed work,” Nerburn said. “Sculpture is not a particularly lucrative profession.”

For two years, Nerburn worked with high school students from the reservation on an oral history project, interviewing Red Lake Ojibwe elders about their memories, traditions and values. Nerburn was amazed by what he learned.

“In the course of that time, I really had a look at the deep spiritual values of the Native people,” he said. “Giving voice to what I was finding out about the Native people to the general, non-Native population felt essential. I found something that felt like a calling.”

Nerburn traded sculpture for writing and spent the next 30 years listening to and working with Native Americans from the Ojibwe, Lakota and Nez Perce tribes. He has written 17 books on spirituality and Native American history and culture. His 1994 creative nonfiction work, Neither Wolf Nor Dog: On Forgotten Roads with an Indian Elder, was made into a film in 2016.

Nerburn will be speaking for Week Seven’s Interfaith Lecture Series, “The Spirituality of Us.” His lecture, “Quiet Voices, Important Truths: Life Lessons from the Native Way,” will air at 2 p.m. EDT Wednesday, Aug. 12, on the CHQ Assembly Video Platform.

In his long career, Nerburn said he has become one of the rare non-Native writers who is largely respected by Native Americans. He credits this to his willingness to listen without judgment or debate, something he learned from his work in oral history.

I look upon creation as a symphony, and each tradition has the capacity to play a different part of the music of creation; each cultural tradition, each religious tradition can play a certain type of music uniquely and in its own fashion,” Nerburn said. “And I think that the Native American way of seeing a larger family, spirit in everything, a humility in the face of the created universe, respect for their elders and a desire not to dominate, but to understand — it may be time for that music to be played a little more loudly than some of the other instruments in the symphony of creation.”

“In oral history, your job is to listen; your job is to just absorb what is given to you and give it back in an articulate, cogent fashion,” he said. “I never had a need to impose myself or my value systems onto the task.”

A necessary part of this work is confronting and understanding how his own biases as a white man influence his worldview.

“I think that really becomes the task of anyone wanting to learn about another way of looking at the world,” he said. “We’re all caught inside our own frame of reference, and it’s become more and more essential to be aware of this over the years — and in the last few years, it’s become absolutely essential.”

The most transformative aspect of Native American spirituality for Nerburn has been the idea that humans do not exist to rule over or control the environment, but are just another moving part within nature.

“The value system for me, the key element among the Native people, is always (that) everything that lives has spirit, and everything out there is a teacher for you,” he said.

This de-centering of humanity is something Nerburn thinks non-Native Americans, particularly Christians, can learn from.

“We are not at the top of creation for the Native people,” he said. “We are the highpoint of creation in the Christian world, made in the image and the likeness of God, whereas for the Native people, we are part of nature — we are not at the top of nature. We were the last of creation to be made, … so everything else is there to teach us.”

He hopes that, if anything good is to come out of the COVID-19 pandemic, it would be that more people begin to understand that they not only move through nature, but are moved by it.

“I think this is a wake-up call,” Nerburn said. “We thought that we were the masters of the environment. I hope this makes us all humbler, and more introspective.”

He is deeply concerned by current politics and the individual-first worldview he has seen grow more and more prominent in the last 30 years. He hopes that now more than ever, his words can introduce more people to Native American spirituality.

“I look upon creation as a symphony, and each tradition has the capacity to play a different part of the music of creation; each cultural tradition, each religious tradition can play a certain type of music uniquely and in its own fashion,” Nerburn said. “And I think that the Native American way of seeing a larger family, spirit in everything, a humility in the face of the created universe, respect for their elders and a desire not to dominate, but to understand — it may be time for that music to be played a little more loudly than some of the other instruments in the symphony of creation.”

This program is made possible by The Robert S. and Sara M. Lucas Religious Lectureship.