At this year’s presentation of The Chautauqua Prize, winner Peter Ho Davies said he was honored — and a little flustered.

“Receiving a prize — with my innate Britishness — makes this quite embarrassing,” Davies said. “But I feel very humbled.”

Davies’ Prize-winning novel The Fortunes follows the lives of four Chinese-Americans in different periods of American history. Davies’ book is the winner from a crop of 192 books submitted for consideration for 2017’s prize. Sherra Babcock, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said the number of entries grows each year, and this year’s number is an all-time high.

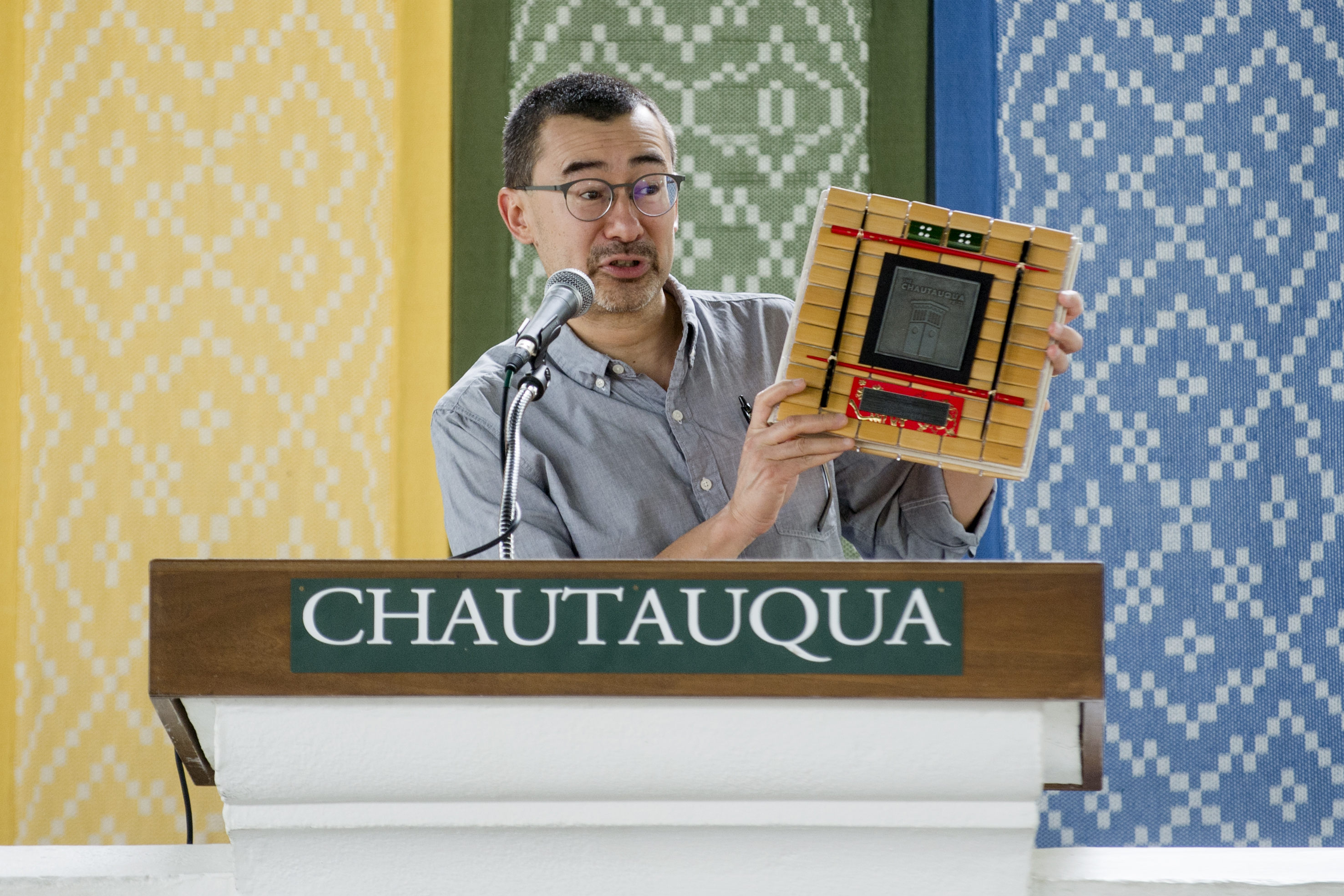

The Prize was officially presented to Davies by President Michael E. Hill on Wednesday in the Hall of Philosophy.

The presentation came after the Prize dinner on Tuesday night, which offers the winning author and the attendees the first chance to see the physical prize. The Prize dinner is meant to reflect the spirit of the winning book, so this year’s event featured a “Farm-to-Wok” theme. Dishes included a main course of five-spice crispy duck with sweet glaze and a dessert of soy-sesame ginger carrot cake, with the majority of the ingredients coming from Chautauqua County.

The physical prize is also meant to honor the winning book. Denise Huck, who created this year’s prize, incorporated representations of gold, silver, jade and pearl into the “memory book” design, as a way of referencing the four sections of Davies’ novel, which are titled “Gold,” “Silver,” “Jade” and “Pearl.”

At the presentation on Wednesday, Davies said that being warmly welcomed into the Chautauqua community is very meaningful to him, especially when he considers that The Fortunes is an immigrant narrative.

Davies said he originally planned on mostly reading from the novel for his presentation, but upon arriving at Chautauqua, he altered his plans.

“What’s really struck me and what I’ve really enjoyed about the Chautauqua experience is the spirit of conversation here,” Davies said.

Davies read excerpts from each of the book’s four sections, pausing to explain his fascination with each character and how they allowed him to explore different questions of representation.

The first section of the novel, “Gold,” focuses on a man named Ah Ling, who serves as a valet for railroad baron Charles Crocker. Ling becomes an integral part of the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad. Davies said he sold the idea to a publisher and worked on it for a few years. After reaching about 100 pages, though, he said, he reached an impasse. Ling wanted to “step out of his novel,” Davies said.

The delay in writing meant Davies had to move the project to a different publisher, which ended up being a blessing.

“Moving to a new publisher allowed me to reimagine the book,” Davies said. “I wasn’t bound to my initial promise with my first publisher, and I could think about how best to present the book going forward in new ways.”

Davies said what drew him to Ling and the other main characters in the novel is that they all struggle with the burden of representation.

“How does one man stand for a multitude?” Davies said. “How does one man stand for a mass? How does one man represent his race?”

These questions led him to the characters who feature in the book’s second and third sections, “Silver” and “Jade”: Anna May Wong and Vincent Chin.

Wong was an actress, and is often considered to be the first Chinese-American movie star. Her career was built on being “professionally, famously Chinese,” Davies said, but that created a strange set of obstacles for her. Wong wasn’t allowed to kiss her white costars on screen because of anti-miscegenation laws, even if the white leading man was performing in yellowface.

These dilemmas opened up a new avenue of questioning representation, Davies said. While the book is about Chinese-Americans, Davies is Welsh and Chinese. He said there’s always an “asymmetry” when it comes to representation in literature, but he liked to work through this asymmetry by having his different characters question where they belonged and who they were supposed to be.

Chin’s section of the novel, “Jade,” gave Davies a chance to investigate misidentification. Chin was beaten to death in 1982 after two white men mistook him for being Japanese. Davies said when it comes to misidentification, many people are guilty.

“We’ve all done this,” Davies said. “I have done this, I should say.”

While that misidentification had tragic implications for Chin, Davies said, it can sometimes be comedic. Davies said he’s been mistaken before for Kazuo Ishiguro, a Japanese-British writer.

“I was disappointed to say that I wasn’t him,” Davies said. “I would love to be Kazuo Ishiguro. I’ve admired him for years, and he’s an amazing writer.”

Davies said he later had the opportunity to tell Ishiguro this story when Ishiguro visited the University of Michigan, where Davies teaches. Ishiguro said it’s happened to him, too: someone once thought he was Jackie Chan.

Chin’s section of the novel is subtitled “Tell it Slant,” which comes from Emily Dickinson’s poem “Tell all the truth but tell it slant —.” Davies noted that Dickinson definitely wasn’t using “slant” in a racist way, but it gave him an opportunity to reclaim a word that’s used to hurt Asian-Americans. He said at one point, the working title for The Fortunes was Tell It Slant, but there were worries over whether the title would make audiences uncomfortable.

The final section of the book, “Pearl,” features a Chinese-American writer named John who struggles with writing different projects about the Central Pacific Railroad, Anna May Wong and Vincent Chin.

Davies said this last section obviously “flirts with autobiography,” but his life doesn’t really resemble John’s all that much. John is offered the chance to write novelizations of the TV series “Kung Fu,” which Davies said is an opportunity he turned down in real life.

Davies said the final section of the book allowed him to truly grapple with the questions of representation that cause him “writerly anxiety.”

“How do I, as a single writer, and a writer of half-Chinese and half-Welsh extraction, represent a community like the Chinese-Americans?” Davies said. “What right do I have to represent them? How can I possibly go about doing that? A lot of it was that question about the right to write.”

That question of the “right to write” and the anxiety it causes can make writers close down and self-censor. For Davies, he wanted to just get it on the page and “do it well, ideally.”

Davies closed the presentation by remarking on the novel’s form. The Fortunes is a blend of history and fiction, he said, and a collection of short stories as well as a novel.

“All of this is to say that the book is hybrid in its form,” Davies said. “And it is, of course, about people, Chinese-Americans, mixed-race characters, who are themselves hybrid in their identities. So by luck as much as by design, by chance, by reading and understanding and slowly feeling my way in the dark toward it — the form of the book actually served the content.”