It’s hard to hear in the Amphitheater sometimes. It’s an issue in 2016, and it was an issue in 1977 when anthropologist Margaret Mead gave a lecture called “The Future as Frame for the Present.”

As she began speaking, Mead immediately asked if everyone in the audience could hear her — in the middle, in the back, at the top, on this side and that.

“Now, if I stop talking into the mic or start dropping my voice — if you will wave, I’ll see it,” Mead said. “If you don’t wave and don’t hear, please don’t go away and complain.”

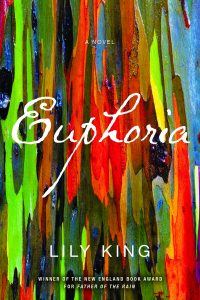

Now, 39 years later, author Lily King will speak on the grounds. Chautauquans will hear about her best-selling novel Euphoria, which was inspired by Mead’s life.

King’s book is the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle selection for Week Five, and she’ll discuss her work Thursday at 3:30 p.m. in the Hall of Philosophy for Week Five’s CLSC Roundtable.

Mead spoke on a number of different topics in her lecture, which was part of a week structured around the future.

She spoke on evolution (she pronounced it “eve-o-lution”). Her consultation on space colonies. People she’d studied who based their counting system around dogs. The dangers of plutonium. How the first chapter of the book of Genesis is a “magnificent statement of evolution, just a little too condensed.” The commonalities between humans and organisms occupying the lowest rung of nature’s ladder.

In a lecture of many different ideas, there was a common theme.

“I think it matters: what we know about the universe and human beings, about all the life in between,” Mead said.

While writing Euphoria, King was much more interested in what Mead called “the life in between.”

She stumbled across a biography of Mead inadvertently, and said she got swept up in Mead’s life, particularly the dynamic of Mead being “embroiled” in a love triangle while trying to do groundbreaking anthropological work.

The novel’s starting point is Mead’s life, but King said she very pointedly decided to take a fictional route with her story. King is a novelist, not an anthropologist.

“I’m just not a nonfiction writer,” King said. “I find writing the facts boring, and I get bored. And I find my writing gets very flat. I’ve only ever been a fiction writer.”

However, King said she was unsure if she was the person to write a novel inspired by Mead’s life.

“I did think it was a good story for a novel,” King said. “But I didn’t think I would be writing that novel.”

She wasn’t even looking for a project at the time, King said. She was working on another: her novel Father of the Rain, which was released in 2010. As she took breaks from writing Father of the Rain and found out more about Mead, King said she’d jot down interesting bits of information in a notebook. That often sparked fictional routes she thought the story could take.

“So it seemed to be triggering my imagination in a way that I didn’t completely expect,” King said. “I guess I had hoped for it deep down, but at the same time, I really went about it telling myself I was not going to write this novel.”

King eventually caved, and began writing Euphoria. The novel was uncharted territory for her as a writer, she said, because her other novels weren’t based on historical figures. King said she created a research syllabus for herself, something she enjoyed.

“It’s always fun to have research,” King said. “It’s like having a helper, an assistant or something. You feel like the pressure isn’t completely on your imagination. And that was new for me, I’d never had that before. And it was kind of fun to have that as a distraction.”

King said she did a lot of reading to find the “handful of details” she needed for her book. She said she was cautious of relying too much on fact, because she doesn’t really enjoy heavily researched fiction.

“You can feel it, you can see it, you can taste it in the paragraph,” King said. “You feel like, ‘Oh, this is a paragraph the author didn’t want to lose.’ But it doesn’t work in fiction. So I was very worried about that and how to incorporate and bring in these things that I learned without making it sound like a dissertation or a bunch of notes, really.”

And even though she had historical facts to fall back on if necessary, it didn’t mean King could get away from the essential work of the novelist: making things up. King said she felt she did the required legwork with her research, but eventually she had to just trust her imagination.

“From the very first page, I just had to start making stuff up,” King said. “It made me so uncomfortable, and it was really the one book where the whole time I felt like a fraud or that I was failing. I really felt failure every day.”

King reached a breaking point about two-thirds of the way through her work on the book, she said.

She felt like giving up, and King’s husband — who she said is the biggest supporter of her work — said maybe she was right. King said her husband is “the last person on Earth who would ever say that” to her, and then she realized how serious the situation was.

“When he said that, I was like, ‘Goddammit,’ ” King said. “ ‘No. I’m not giving up. I’m going to keep going.’ ”

She did.

King finished Euphoria, and it became a best-selling and critically successful work.

It was a surprising feeling, King said, because she thought it would be a “minor work” in her career. When she sent her agent the manuscript for the work, she said she got a text back that said “I LOVE THIS BOOK SO MUCH.”

“That was such a great moment — one of the highlights,” King said. “I didn’t have any confidence in it. I thought people were just going to laugh their asses off at me for having written this book.”

Euphoria has garnered acclaim for King — it won the inaugural Kirkus Prize for Fiction, was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and was part of The New York Times Book Review’s 10 best books of 2014, among other honors.

It was also a finalist for the 2015 Chautauqua Prize, which is how it came to the attention of Sherra Babcock, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education.

As planning began for 2016’s programming, Babcock said Euphoria felt like a perfect choice for Chautauqua due to the book’s connection to Margaret Mead. She said it was also an obvious fit for the theme of Week Five, “People and Environment,” which is presented in partnership with the National Geographic Society.

King’s presentation on Euphoria also comes during a season asking the question of what it means to be human — one of the central questions of anthropology.

Bethanne Snodgrass, who did a mini-review of Euphoria on Monday for a CLSC Brown Bag Monday, said what impressed her about the book was how relevant it felt, despite the historical setting.

“The thing is that when you read it, you cannot help thinking these are the same conversations we’re still having,” Snodgrass said. “We still haven’t figured that out. There’s still a huge segment of our society who cannot perceive people different from themselves as being equal.”

King takes those issues and filters them through the human experience, Snodgrass said.

“These anthropologists are working through this, and she does a wonderful job, I think, of condensing these ideas running through these people’s minds,” Snodgrass said. “It certainly strikes a chord.”

For King, the book is about individuals looking to expand the definition of what it means to be human, especially beyond a Westernized conception of humanity.

“I feel like the book is really about three people who travel far away to find the limits of humanity and how we define it — and how we redefine it — as a modern culture,” she said.

In the midst of their anthropological work, the three people become involved in a love triangle, a dynamic King said she found engrossing. She said she was interested in the claustrophobia of their situation. Because anthropologists were usually funded by grants, they had to stay and get their work done, regardless of personal circumstances.

“That environment of claustrophobia is really compelling to a writer,” King said. “There’s no escape route, there’s no more oxygen to put into the room. You have to push them to their expiration point, almost.”

Ultimately, King thinks Euphoria is a love story about work, something she came to appreciate as she finished the book.

“I think people love to escape,” King said. “I feel like I learned a lot from writing this book and what people took away from it. I think it’s a combination of the very unfamiliar landscape as well as the focus on work. I feel like a lot of people have commented on that: that it was not just a love story between a man and a woman or two men and a woman or whatever, but that it was really a love story about work — the importance of work, the passion of work. I just wonder if that had something to do with it, too.”

The rewards of her work will bring King to Chautauqua, which means she’ll be walking the same grounds Mead did nearly four decades ago. It’s a prospect King said is “a little daunting.”

“I guess I just hope she’s OK with that — with the book and the project and the whole concept of it,” King said. “I wish so much that I could have met her and had a conversation with her — that we could sort of collapse the time-space continuum so we could have that moment together. It’s quite an honor.”