At any given moment, there are about 7,000 aircraft in the sky, according to the National Air Traffic Controllers Association.

A little more than a century ago, it seemed unfathomable that one plane could make it into the air — except to the Wright brothers.

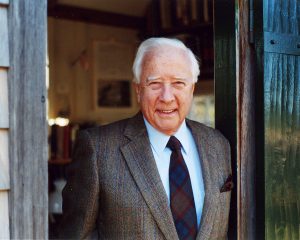

Esteemed historian and two-time Pulitzer Prize winner David McCullough will discuss the famous brothers and their legacy at 5 p.m. Wednesday in the Amphitheater as part of Week Four’s Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Roundtable. His 10th book, the New York Times best-seller The Wright Brothers, is the CLSC selection for Week Four.

It’s easy to think of the Wright brothers and their accomplishments as the success story of a simpler time, but McCullough said there’s no such thing.

“There never was a simpler time,” McCullough said. “There never was a time where there weren’t serious problems. There never was a time where there weren’t ample expressions of greed and evil, and goodness and kindness and loyalty and courage. Courage is so important. An awful lot of what history is about is courage, and particularly, the courage of our convictions.”

It’s something the Wright brothers had in spades, McCullough said, because they were raised with the ideology that life ought to have a purpose. That was instilled in them by their father, Milton Wright, he said.

“He didn’t preach to them what that purpose should be, but that the good life was a life where you believe in the value of work and you kept to it and you worked hard,” McCullough said.

In a season at Chautauqua Institution focused on what it means to be human, McCullough said the Wright brothers demonstrate “a number of very admirable human qualities at their best”: loyalty, generosity of spirit, persistence and passion in their work.

The Wright brothers were also incredibly modest, a quality “not much in fashion anymore,” McCullough said. He said one of the “most telling and delightfully amusing examples” of that was their reaction to a huge celebration thrown for the brothers in honor of their accomplishments in their hometown of Dayton, Ohio.

“And they took part in it,” McCullough said. “But any time there was a break, they would slip away and get back to their shop to work on whatever project they had underway. To say that the glory and glamour of fame did not go to their heads is an understatement.”

They also had a healthy intellectual curiosity, McCullough said, citing what’s become his signature line.

“I contend that curiosity is what separates us from the cabbages,” McCullough said. “That’s a very human quality: curiosity. And it can lead to wonderful progress of the best kind.”

It’s those small but personal particularities that draw McCullough into his work. He said he thinks of himself not as a historian or a biographer, but as a writer who “writes about what really happened to real people.”

“More than anything else, it has to do with the people,” McCullough said. “It’s finding that I really want to know these people better. I really want to go into their lives and be with them. And I get excited about how much I’m going to learn from them, not just how much I’m going to learn about them.”

McCullough has learned from and about a number of people over the decades through his nine previous books: John Adams, George Washington, Theodore Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, to name a few.

Someone he learned about and from in his research for The Wright Brothers was Katharine Wright, Orville and Wilbur’s sister.

“One of the joys of the book was to bring Katharine front and center stage, because she’d never been there before,” McCullough said. “She’s mentioned, and she comes and goes, but I don’t think the story would have come out the way it did without her playing the part she did. She’s refreshingly different. She said she could get ‘wrathy’ and ‘bossy,’ and she had humor and she liked being with people.”

Part of the delight of uncovering unexpected information comes from McCullough trying to have minimal knowledge about the subject he wants to write about before he starts researching. He said if he already knew too much about what he wanted to write about going in, he wouldn’t want to write about it.

“It’s like going on a journey to a continent you’ve never set foot on,” McCullough said. “Every day, I’m learning something. It’s the pursuit, the hunt, the detective case that makes you want to get up out of bed in the morning and get back to work.”

Besides learning more about the “wrathy” Katharine, McCullough also unearthed a figure from the Wrights’ past who hadn’t been discussed at length before: Oliver Crook Haugh. He has somewhat faded from history, but McCullough found an interaction between Haugh and Wilbur interesting — he hit Wilbur in the face with a hockey stick during their adolescence, “knocking out most of his upper front teeth,” McCullough wrote in The Wright Brothers.

Haugh then went on to become the “most notorious mass murderer of his time in Ohio,” McCullough said.

“You won’t find that in other books,” he said.

He felt like that changed the story, McCullough said, and it gave him greater insight into Wilbur’s personality. McCullough wrote in The Wright Brothers that after the incident, Wilbur was fitted for false teeth, suffered from numerous health problems and became very reclusive.

“Clearly it changed the course of his life,” McCullough wrote in the book.

Discoveries such as those have happened with each book he’s written, he said.

“Every book, each and every book, something has turned up that hadn’t been known about before,” McCullough said.

McCullough’s presentation comes during Week Four, which is structured around the theme of “Our Search for Another Earth.”

It’s a week on hard science and the search for other planets, said Sherra Babcock, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education. But what McCullough brings to the week, Babcock said, is a different angle into the idea of human innovation and invention.

McCullough has visited Chautauqua many times. He spoke as part of the morning lecture series six times from 1986 to 1993, and his book Mornings on Horseback was a CLSC selection in 1982. A special program, “An Evening with David McCullough,” was held in the Amp in 2009.

Babcock said she was delighted to invite him back and to hear his perspective on the week’s theme, particularly because “he is absolutely one of the best lecturers in the country.”

“He gives us a contrast of storytelling and history, and it’s all so very relevant to what we’re talking about,” Babcock said. “It’s not directly involved with the topic, but if you’re going to talk about our search for other planets, isn’t it intriguing that the book that’s chosen is about the first time that Americans left the ground?”

McCullough said our point in the “odyssey” of progress would be “far beyond” the Wright brothers’ imaginations.

“But I think they would applaud it — the endless pioneering of the human mind, the endless desire to know more, the love of learning, the impulse for growth and possibilities and the creative,” McCullough said.

McCullough believes it’s important to recognize, appreciate and celebrate this odyssey of progress, and not just to focus on human turmoil.

“One of my strongest feelings is that history is much, much more than just about politics and war,” McCullough said. “Yes, politics and war are a huge part of history. But let’s not leave out so much that matters as much or more in the human experience — art, music, poetry, science and technology, medicine, finance, astronomy — some of those things are happening right under our noses.”

McCullough explored a similar theme in The Wright Brothers. Through the lens of Wilbur and Orville’s lives and work, he tracks society’s shifting attitude toward aviation in the 20th century. Part of that shift was the media’s portrayal of the brothers and their endeavors.

“When the city editor of the Daily News, Dan Kumler, was asked later why for so long nothing was reported of the momentous accomplishments taking place so nearby, he said after a moment’s reflection, ‘I guess the truth is that we were just plain dumb,’ ” McCullough wrote in The Wright Brothers.

There are countless examples of that type of negligence throughout history, McCullough said.

“Were they ever dumb, my God,” McCullough said. “It’s a funny thing. People are so accustomed to knowing that something isn’t true, that even if you tell them that it is true, they still don’t believe it’s true.”

So what is the world being dumb about now?

McCullough had multiple examples of the world’s willful ignorance: the disrepair of infrastructure, the lack of control over guns and the “poisonous effect” of big money on politics.

“That’s three of them, right there,” he said.

But McCullough still considers himself an optimist, he said. People who have courage in their convictions, like the Wright brothers, can change the world.

A clear example that’s touched him personally, McCullough said, is how far medicine has been developed in his lifetime. McCullough said his brother, as well as his brother-in-law, were afflicted by polio, but Jonas Salk’s development of the polio vaccine changed what used to be just a fact of life.

People can easily take advancements such as those for granted, he said.

“We should be down on our knees thanking the human mind as well as the lord above for the benefits we’ve been gifted with,” McCullough said.

And that’s what McCullough thinks people can learn from the Wright brothers, and those cut from the same cloth.

“We are very lucky to be the beneficiaries of so many brave, ingenious, dedicated and patriotic forebears,” he said.