As young Catholics, Protestants and Jews continue to fall away in record numbers from the faith embraced by their parents and grandparents, there is one religious group that is retaining its young people and growing in leaps and bounds as a result: the Amish.

Nearly 300 years after the first Amish arrived in America in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, there are more than 300,000 Amish in 31 states and three Canadian provinces, according to the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown College in Pennsylvania. The center also estimates that there are about 18,000 Amish in New York state, many of whom live in Chautauqua and Cattaraugus counties. It predicts that the number of Amish will exceed 500,000 in 20 years.

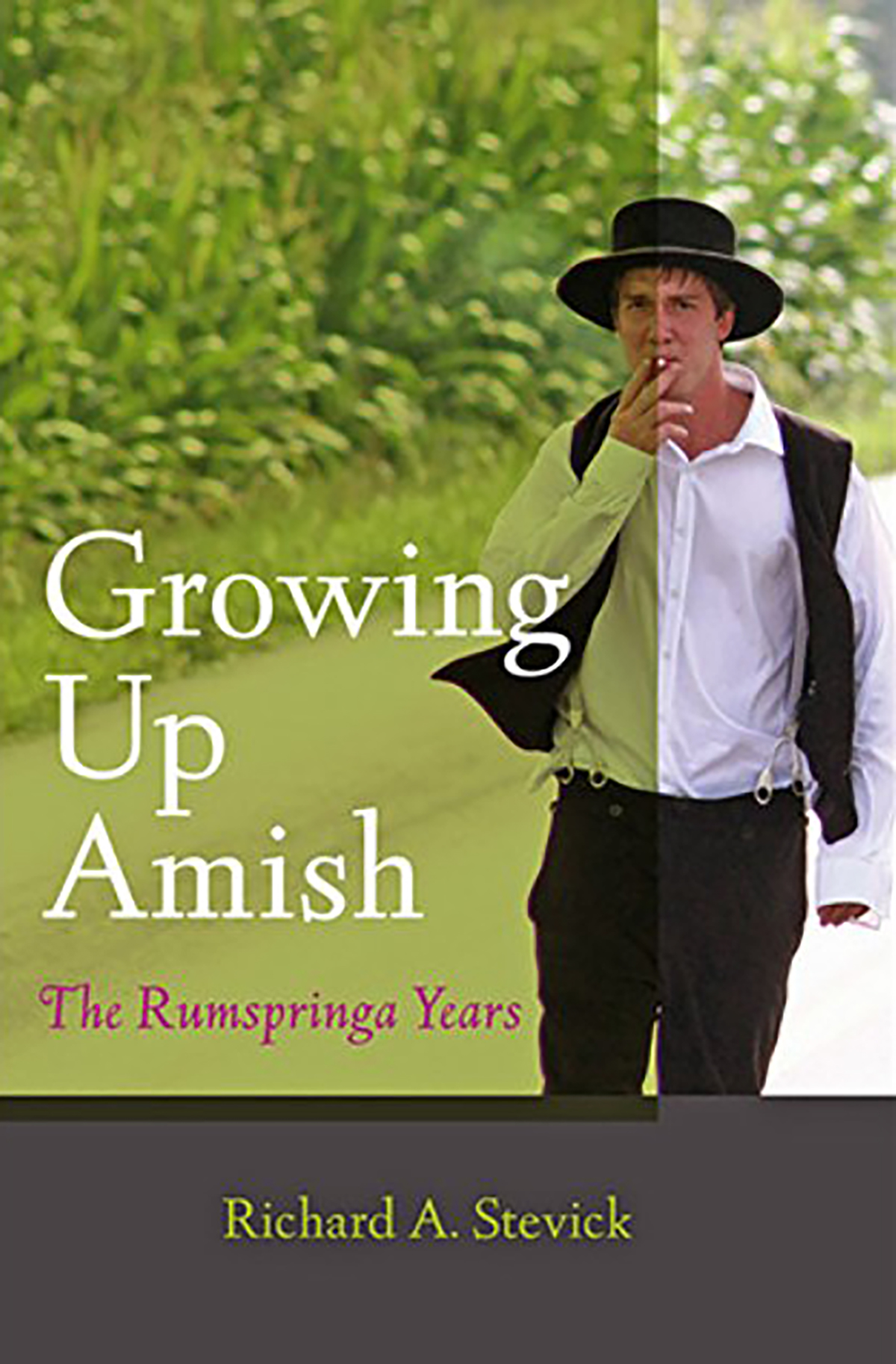

Richard A. Stevick is a professor emeritus of psychology at Messiah College in Pennsylvania, where he also taught courses on Amish life. He has been studying the Amish experience in America for 25 years and is the author of two books about Amish young people: Growing Up Amish: The Teenage Years and Growing Up Amish: The Rumspringa Years, both published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

At 3:30 p.m. Tuesday in the Hall of Philosophy, he will deliver a lecture on “The Amish Experience: Paradoxes, Lessons and Surprises” as part of the Oliver Archives Heritage Lecture Series.

“I want to try to see how Amish life has survived over the past 300 years,” said Stevick, who lives in Holmes County, Ohio, which has the largest population of Amish in that state. “Back in the 1950s, sociologists said they thought Amish life was coming to an end in America. In the 1960s, I thought they were two generations from extinction. They have doubled their numbers every 20 years since then.”

Stevick said that he has taken groups of students to Central and South America to study other cultures there.

“You see young people participating in traditional ceremonies, then, when those things are over, they’re right back in their jeans and on their cellphones,” he said. “They are not continuing their culture beyond acknowledging the history.”

Amish young people commit — or don’t commit — to their religion and community in their late teens or early 20s, after a period called Rumspringa (loosely translated from Dietsch, or Pennsylvania Dutch, as “running around”). Teenagers, who have completed the equivalent of eighth-grade in an Amish school and have perhaps worked on the farm for a couple of years, are encouraged to take a year or two, up to five years, to explore the world outside their insular community. Then they choose whether to be baptized.

“Eighty-five percent decide to stay and make a lifetime vow,” Stevick said. “The whole society is built around that choice to give themselves up from selfishness and devote themselves to family life, collective life, the life of the community.”

He said that tales of drunken debauchery and wild living among the teenagers during Rumspringa are “way exaggerated” by the media.

“They are really pretty placid,” he said.

Likewise, stories of children excommunicated and forever shunned by their families are also blown out of all proportion.

“If they don’t join the church, they cannot be excommunicated,” Stevick said. “If they haven’t made those vows, they are not shunned.”

The Amish are a relatively young group in the greater scheme of world religious movements.

During the theological upheaval of the Protestant Reformation in Europe, the concept of infant baptism as practiced by the Catholic Church came into question by reformers who argued that only adults who had rationally accepted their faith should be baptized. In 1536, many of these Anabaptists — as they were called — joined a group led by Menno Simons, a Dutch former Catholic priest, and became known as Mennonites. In 1693, a splinter group headed by Jakob Ammann broke away from the Mennonites over the concept that unrepentant sinners must be excommunicated and completely shunned by the community. They became the Amish.

The early Amish were harshly persecuted by both Catholics and Protestants. Thousands were killed for being heretics. Many fled into the hills and mountains of Switzerland and Bavaria, where they set up the small, subsistence farms and home-based religious services still associated with Amish people today. As they remained under siege, a sizable group accepted the offer of William Penn to relocate to the religiously tolerant area of the New World that would become Pennsylvania. The Amish began arriving in Lancaster County in the 1720s.

Stevick said he became interested in the Amish after reading an article in National Geographic in 1965 that described life in Lancaster County. He and his wife visited and tried to strike up conversations, but were politely rebuffed.

Years later, Stevick was teaching psychology at Messiah College when a colleague who had been offering a course on Amish life retired and asked him to continue the program. He agreed, and began to meet a few Amish people in the course of studying them. Stevick and his wife were lukewarmly welcomed to stay with the brother-in-law of an Amish friend, but by getting up at 4:30 a.m. to milk cows, pitch manure and do other chores formed a close friendship that lasts to this day.

The one thing that could threaten the traditional Amish lifestyle, Stevick fears, is the internet.

Although there are varying levels of strictness among Old Order and New Order Amish, with some resisting most modern technology and others embracing some aspects, Stevick said most young Amish he knows use cellphones or computers.

“The most conservative are the least likely to use technology, but more progressive groups use it routinely,” he said. “Many of the Amish teenagers I know have Facebook accounts and are skilled with the technology.

“The No. 1 concern among the adults is that cellphones can expose their children to pornography, or that after five years of being on Facebook, it may be hard for them to give it up,” Stevick added. “They are concerned about the cohesion of the community and how to retain their simple, Christian values.”