In a country so polarized by the current political climate, this exhibition serves as a reminder of that which ties together all of us living here now: the land itself. The landscape in American history has been more than that upon which we walk; rather, it has become an epic character of its own, representing opposing positions since its beginning. It is an indigenous homeland, but also an occasion for European colonization. It has expanded its power into foreign territory, yet has also offered a home to immigrants. Nature can be peaceful, or it can be horrifically destructive. America has been, and continues to be, a place with vast extremes of poverty and wealth. These oppositions are irreconcilable, yet, as the title of this exhibition, “Resting Place” suggests, the vast landscape of this country, regardless of its struggles, is “home.”

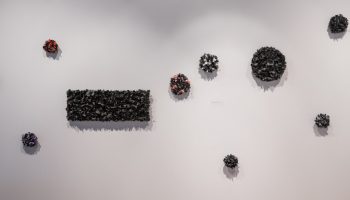

Curated by Judy Barie, the Susan and Jack Turben Director of Galleries for the Visual Arts at Chautauqua Institution, each artist presents a unique version of the American landscape as a tranquil site where we can go to refresh, renew and reflect. Dotted throughout the center of the gallery are Wisconsin-based sculptor and furniture maker Jim Rose’s steel structures. These three-dimensional, mostly pentagon sculptures reference simplified houses or sheds, each with a distinctive surface. Some are open structures, some closed, some with a colored patchwork pattern, and others monochrome, none more than 16 inches tall. They each have a worn and patinated surface, suggesting well-loved rural homesteads. Individually, they are stunning, but arranged throughout the gallery they appear like a village, with the backdrop of land and sky created by the other artists’ two-dimensional works hung on the walls behind.

[huge_it_gallery id=”49″]

Thomas Paquette, based in Warren, Pennsylvania, takes a more traditional approach to representing his vision of the landscape. Small works, like the oil-on-panel “In the Element” and a series of three gouache-on-paper sketches, no more than a few inches wide, present the epic grandeur of the sky on an ironically small scale. His larger works, done on a scale more traditional to landscape painting, like “Power in Late Day,” with its acidic green trees and purplish sky, showcase the endless, chromatic variety of nature.

In a series of smaller photo-based works, hung gallery style, bookended by larger ones, Guyana-born, Brooklyn-raised, Pittsburgh-based Gavin Benjamin offers a visual journey. A few shots of aged interiors with a lone piece of furniture, perhaps the beginnings and ends to the journey, are presented with imagery of barns, the prairie, lone trees and forests, much like a cross-country photo album. From afar, the images seem to be straightforwardly photographic, but up close a secret is revealed. Small segments of each photograph, for example, a shed in the corner of one or the bottom third of the landscape in another, have been cut from the scene. These pieces were reattached to the surface, slightly off-kilter, on a piece of thin wood, some hanging just slightly off the edge of the panels upon which the image is affixed, perhaps referencing the man-made impositions into otherwise pastoral landscapes.

Sara MacCulloch and Nicole Renee Ryan make works that play with the idea that it is nothing other than a horizon line which dictates the form of a landscape. Both artists make works that push the boundaries of how far toward abstraction a painting can go, yet still retain its landscape identity. Two works by Nova Scotia-based MacCulloch, “Field and Trees” and “Kingsport Dusk,” in a very non-landscape, square format, are horizontal strips of color with loose, bravado brushwork throughout. Her color choices are as much about interactions of color as they are about literal representation; the more recognizable elements, for example, small groupings of trees or patches of grass, are opportunities to explore wet-on-wet paint techniques and calligraphic brush strokes. The paintings, done mostly in one sitting, have a sense of immediacy. In her artist statement, she notes that she does not have an exact idea of the image before she begins, but allows serendipity and her relationship to the painting to dictate its form. Pittsburgh-based Ryan also works with imagined landscapes, and her goal, as mentioned in her artist statement, is to recreate a place you feel you know but can’t identify. Ryan’s stunning watercolors on yupo paper, titled “In Other Words” and “Long a Coming,” are explorations in layering and paint application. In both, moody skies are opportunities for the watercolor to be brushed and dripped, layered and swiped across the surface using colors both heightened and surreal.

Finally, Peter Hoffer, Canadian-born and Berlin-based, creates paintings of trees, suggestive of scenic backdrops. The surfaces are stressed and intentionally overworked, then coated in shiny resin. This, as described in his artist statement, is appropriated from a common practice among 19th-century painters to revarnish unsold paintings before a new exhibition to make them appear “fresh.” In Hoffer’s hands, the repeated, layered varnish is allowed to become imperfect. As he states, the controlled hand of the artist and the force of the material are at odds. The painting adopts certain characteristics of the landscape, changing and evolving as materials break down and the composition is thus altered. This is exemplified in “Basel.” Layers of underpainting are visible along the edges, and delicate paint cracks and scratches decorate the surface. Small dots of sprayed blue and turquoise paint look like graffiti marks on the painting, like a collision of the historical and the contemporary. Beauty is found in the imperfections.

Perhaps, rather than search for a collective consciousness that does not exist, the varied work by these artists — who represent Canada, South America, Europe and this country — provides the answer: an acceptance that the individual vision is our collective.

Melissa Kuntz has written for many publications, including Art in America magazine and the Pittsburgh City Paper. Her paintings and drawings have been shown in Canada and the U.S. She is full professor of painting and drawing at Clarion University of Pennsylvania and is working part-time toward a Ph.D. in applied sociology at Indiana University of Pennsylvania.