A voice has been given to the voiceless — and it is perfectly in tune.

A voice has been given to the voiceless — and it is perfectly in tune.

Richard Bogomolny, creator of the Violins of Hope Project,” will host a presentation and Q-and-A for the “Violins of Hope” documentary, shown Sunday in the Everett Jewish Life Center at Chautauqua, at 3:30 p.m. Monday in the Hall of Philosophy. The film will be screened again Wednesday at the EJLCC.

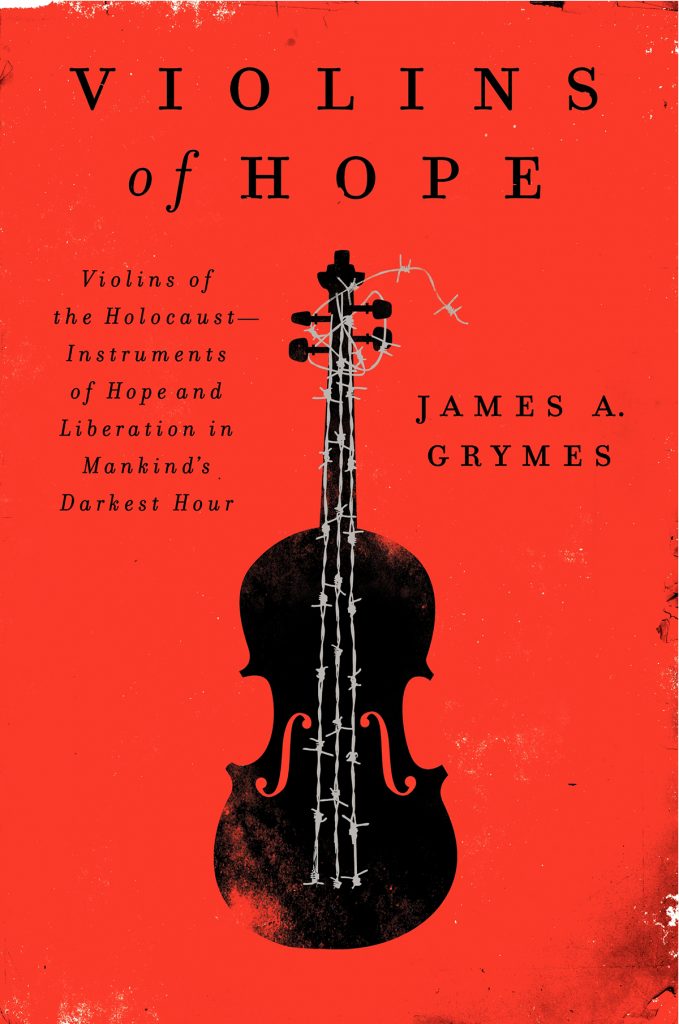

The hourlong documentary’s focus is the finding and repair of violins which survived the Holocaust, even when their owners did not. Amnon Weinstein, a master violin maker from Tel Aviv, Israel, has devoted his life to locating the instruments. The idea was that if he could restore the violins for modern musicians to play, a renewal in Jewish culture could be established.

Bogomolny first heard about the story of violin restoration in 2012. Playing the violin as a child and his 28-year connection with the Cleveland Orchestra motivated him to gauge his community’s interest in learning more.

It was a three-and-a-half-month startup process, including lectures, concerts and readings. Bogomolny created an initial team of seven nonprofits. Their first step was reformatting of the documentary by Ideastream so it could “serve as an introduction to the story of the Holocaust and the violins, so it could be used by teachers everywhere.”

“We had ultimately written curriculum for all of this,” Bogomolny said. “It was introduced into many of the school systems around here. … Many of the schools decided that the program was powerful enough teaching the lessons of the Holocaust that they would build this kind of program into their curriculum.”

Bogomolny is not an educator. He has run a supermarket company for the past 27 years and served as both president and chairman of the board of the Cleveland Orchestra. He simply wanted a way to expose people to the horrors of the Holocaust and the hope of the violins — and he wanted to do it quickly. In doing research for the project, Bogomolny spoke with Abraham Foxman, former national director of the Anti-Defamation League.

“(Abe) said the most difficult thing today about teaching the lessons of the Holocaust is that students today, and even their parents, didn’t live through the period,” he said. “His comment to me was it’s kind of like trying to teach the story of the pharaohs and the pyramids. You understand it intellectually OK, but there’s not much of an emotional connection, and it’s emotional connection that really causes people to take stands, to take action, to do something.”

So the Cleveland Institute of Music, the Cleveland Orchestra, Case Western Reserve University, the Jewish Federation of Cleveland, Facing History in Ourselves and the Maltz Museum of Jewish Heritage came together. Fourteen other nonprofits eventually joined them.

Suddenly there were stories everywhere. Weinstein began to receive calls from all over the world from people who were motivated to do their own version of the Violins of Hope Project. The Toronto Symphony Orchestra, for example, followed suit with the Cleveland Orchestra.

“Because of what went on at Cleveland, we put (Amnon’s work) on the world map,” Bogomolny said. “(We wanted to) put this on at a very high level and be able to assist other places in doing the same thing.”

Weinstein never saved the violins for financial gain. He just wanted viewers to learn.

“Amnon never made a penny. It was all out of pocket expenses,” Bogomolny said. “He not only supplied the violins, but in some cases, they took up a year to a year and a half to fix.

“The documentary not only is a teaching instrument, but a way of getting the message out so other areas who are interested are able to do it. It’s kind of self-perpetuating.”