You’ve heard all about it, and Monday is the day: A total eclipse of the sun will occur across a large swath of America starting from the Oregon Coast in the morning to the beaches of South Carolina in the late afternoon, the first such celestial event in the United States in 99 years.

Millions of Americans are expected to view the rare phenomenon. Even Bonnie Tyler, who had a top hit 1983 with “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” will be belting that song out on a cruise ship with one of the Jonas Brothers at the exact moment the moon eclipses the sun.

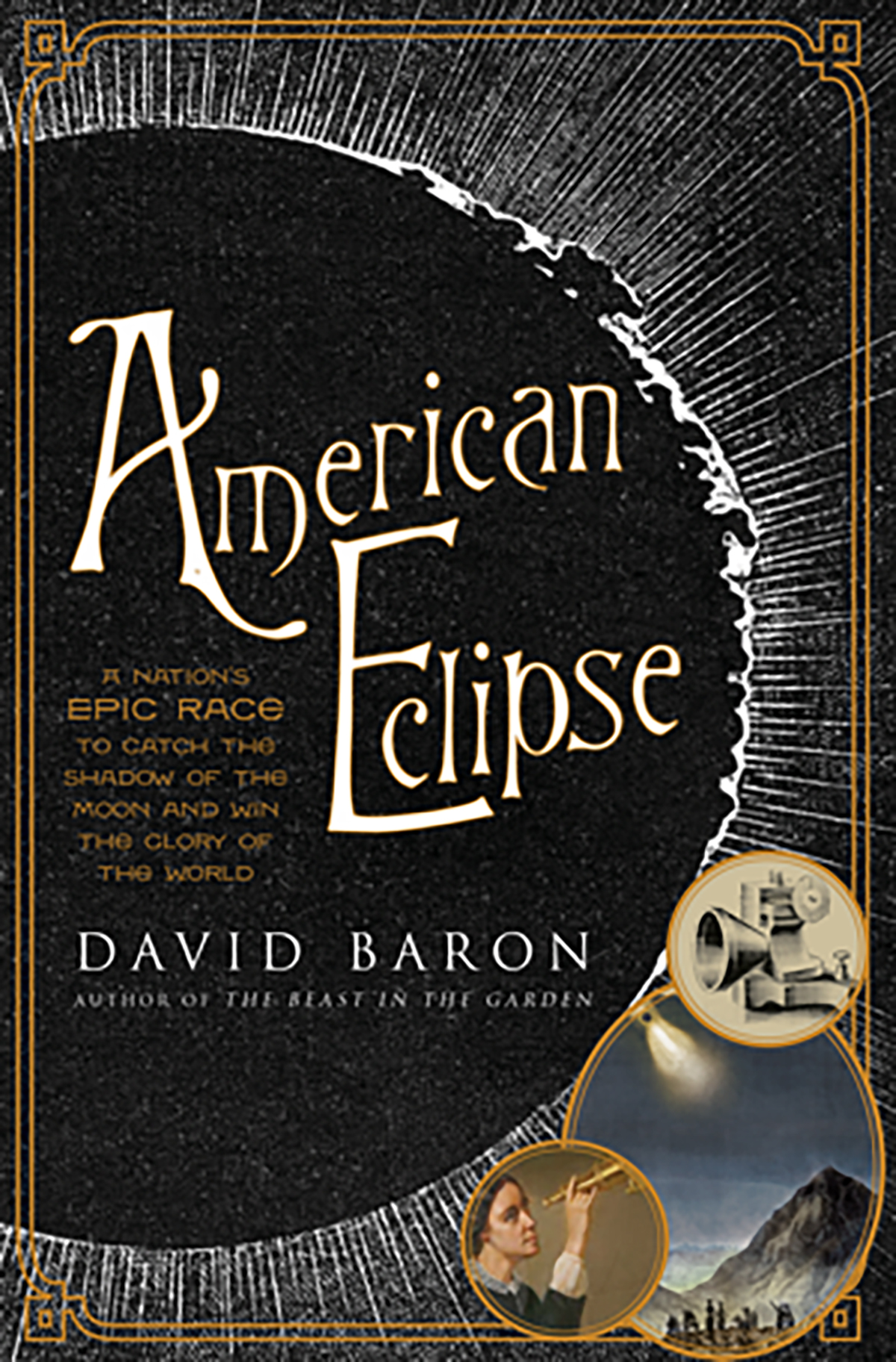

Viewed from here, the event will not actually be a total solar eclipse, but 77.4 percent of the sun will appear covered by the moon at its peak at 2:34 p.m. The next time a total eclipse can be seen from Chautauqua will be on April 8, 2024, according to David Baron, an eclipse chaser and the author of American Eclipse, which is about the total eclipse in 1878 and which prominently features Thomas Edison, who had a longstanding relationship with the Institution.

Baron will view the eclipse from the 11,000-foot summit of Rendezvous Peak in the Teton Mountains at Jackson, Wyoming, while Edison watched it from Rawlins, Wyoming, about 285 miles southwest. Baron noted that the 2017 eclipse follows almost exactly the same path as the one in 1878.

A journalist and broadcaster with many years in public radio, Baron saw his first total eclipse in Aruba in February 1998.

“It was just a mind-blowing, spectacularly moving experience,” he said. “It got me hooked. I got the idea for writing a book that day. It took me 19 years, but I also wanted to time it to come out just before the eclipse of 2017.”

Since Aruba, Baron has witnessed total solar eclipses in Germany in 1999; Australia in 2012; the Faroe Islands in 2015 and Indonesia in 2016. That sounds pretty impressive, but some umbraphiles, as eclipse chasers are also known, claim to have seen as many as 46.

Do a lot of people chase eclipses?

“More than you would think,” Baron said. “It’s in the thousands worldwide. There is a website called eclipse-chasers.com that has 800 members. They log their eclipse sightings much the way birders log birds they have seen.”

According to the Buffalo Astronomical Association, the partial eclipse will be visible from Chautauqua beginning at 1:11 p.m., with the 77.4 percent eclipsed by the moon at 2:34 p.m., and ending at 3:51 p.m.

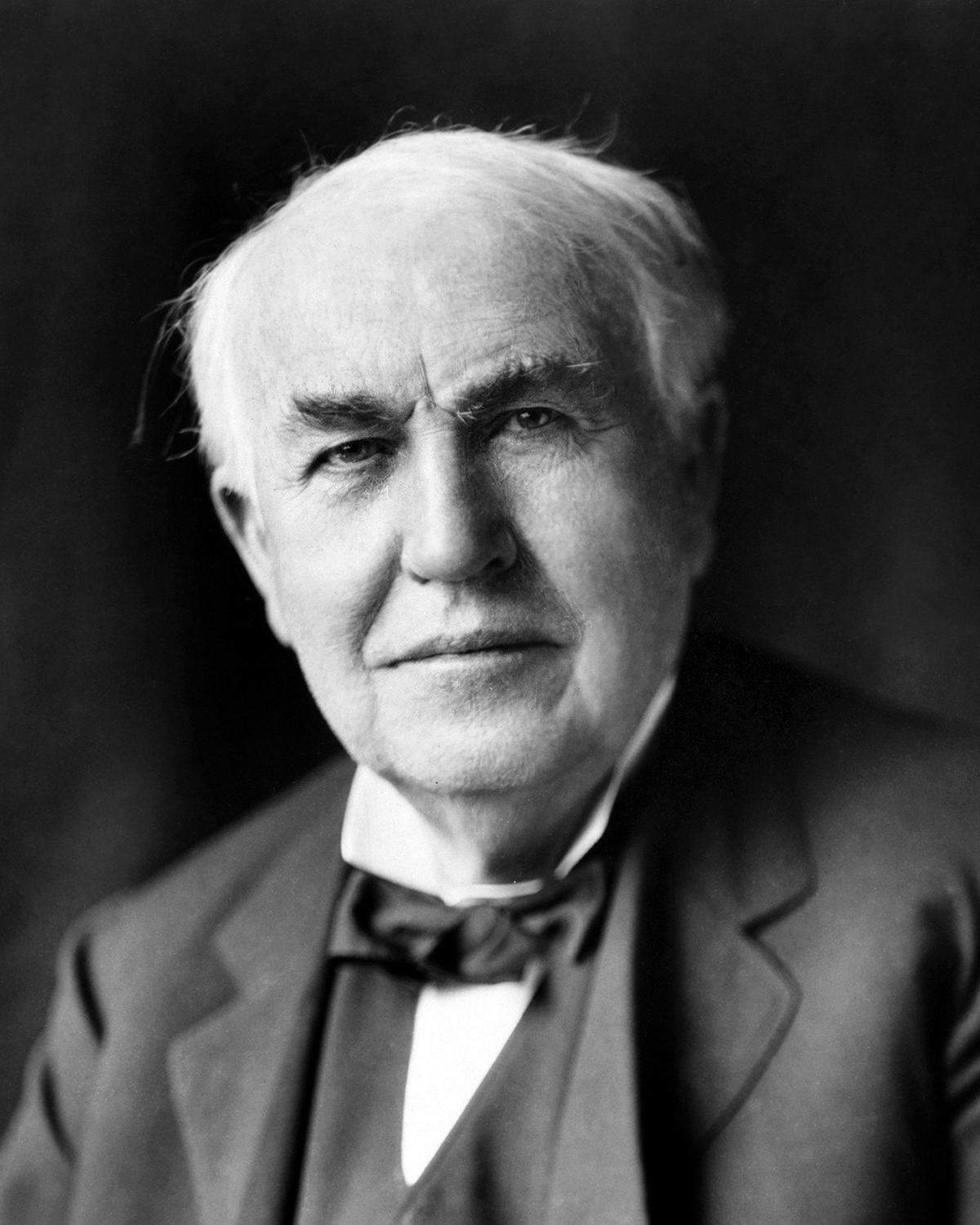

Which brings us back to Thomas Edison.

Edison, of course, is perhaps the most famous inventor in American history, credited with coming up with the phonograph, the electric light bulb, movies and much more. He was also married to Mina Miller, the daughter of Lewis Miller, a successful industrialist and philanthropist from Akron, Ohio, who along with the Methodist bishop John Heyl Vincent founded Chautauqua Institution in 1874. Edison proposed to her using Morse code, tapping out his intentions on her leg during a carriage ride in 1885. They were married at the Millers’ Akron estate and were together for 45 years, until his death in 1931. Many of their holidays and summers were spent at the Miller Cottage, the oldest house on the grounds.

In the summer of 1878, Edison was only 31, but was already widely celebrated. He was also shrewd at publicizing himself. Local lore in Wyoming has it that Edison came up with the idea of an incandescent light bulb after watching the eclipse, or after marveling at the stars in the Wyoming sky. Another tale has Edison striking on the idea of bamboo as filament after he threw a broken bamboo fishing pole into a campfire at Battle Lake and watched it burn brightly.

“These legends are just not true,” Baron said.

Yet, as with many myths, there are kernels of truth in them. And his experience in Wyoming had a big impact on Edison.

“It’s a fascinating time in the life of Thomas Edison,” Baron told Knowledge@Wharton, a publication of the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, earlier this month. “He went west in 1878 for this total solar eclipse, right after he had become a global celebrity because of his invention of the phonograph. The very day after he returned from Wyoming, he started work on the light bulb. There are some subtle ways in which his eclipse expedition helped him with the light bulb, most importantly because of what he learned about public relations, which was key to his ability to raise money and keep the press on his side while he worked and worked and worked to perfect the light bulb.

“Edison was a natural with PR, but in the summer of 1878, he just had the newspapers wrapped around his finger,” Baron went on. “He headed west for the eclipse. He came up with device called the tasimeter, which was going to be ‘bigger than the phonograph,’ as the newspapers said. It was a very sensitive heat detector that he was going to use to study the eclipsed sun. He had the newspapers writing glowing reports about the tasimeter even before he had ever created it. That’s the same thing he did with light bulb. He claimed that he had solved the problem of incandescent lighting long before he really had, but he kept the press on his side until he actually did solve the problem.”

American Eclipse, which was published in June and has already gone through three printings, is about much more than Edison. Besides the eccentric inventor, Baron focuses on Maria Mitchell, a Vassar astronomer and president of the American Association for the Advancement of Women, who was out to prove that women could be as adept at science as men, and on cosmologist James Craig Watson, who was hoping to discover a new planet. But it is the eclipse itself that really holds the limelight.

“Eclipses, I find, connect the present with the past like few other natural events,” Baron writes in American Eclipse. “For me, personally they are life milestones. Each forces me to reflect on who I was the last time I gazed at the corona. For us, collectively — as a society, a nation, a civilization — they can have the same indelible, life-affirming effect. They afford a chance not only to grasp the majesty and power of nature, but to wonder at ourselves — who we are, and who we were when the same shadow long ago touched this finite orb in the boundless void.”