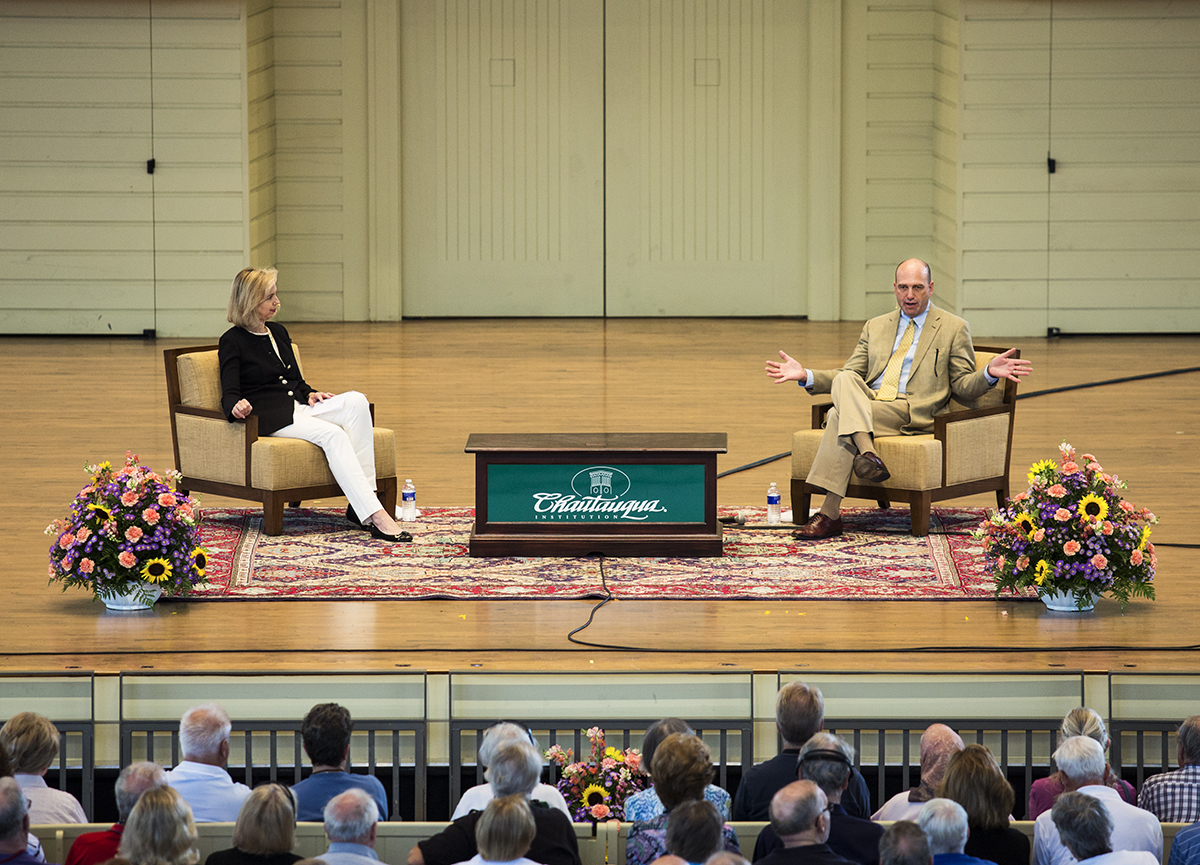

Nancy Gibbs and David Von Drehle have been talking with one another for 30-some years. Their joint presence on the Amphitheater stage Thursday morning, therefore, was more a continuation of a decades-long conversation than anything else.

And as Von Drehle leaves Gibbs behind and moves from Time magazine to The Washington Post, their dialogue took on special significance.

“Consider this an exit interview,” Gibbs suggested, “conducted in front of 5,000 people.”

After all, Gibbs is the current managing editor of Time, and Von Drehle was its editor-at-large for 10 years prior to becoming a Post columnist just this month. Together, the duo brought years of experience with both the press and each other to Week Eight: “Media and the News: Ethics in the Digital Age.”

They opened, as one might expect from journalists, with current events.

“Both of us found ourselves having to write about Charlottesville this week,” Gibbs said, referencing the white supremacist rally that had occurred in the town days earlier. “And that is a particularly difficult (one) of our many different national tragedies and conflicts that we’ve wrestled with, and so I wonder how you — particularly in your new role, not writing the news but writing what you make of it — how you thought about it.”

Von Drehle traced it all back to recent innovations in digital communications that have, as with the Gutenberg printing press before them, rewoven the fabric of political engagement.

“How much is the world going to be changed by supercomputers in the palms of our hands; the ability of every person on the face of the Earth to become their own media producer, their own media aggregator, their own managing editor for their own mindspace?” Von Drehle asked. “So that’s the background of Charlottesville.”

There have always been “hateful or exclusionary” people in the United States, he added, but those people used to communicate slowly, via mimeograph. Now, those same people can organize in an instant.

One would hope for strong national leadership in this fraught context. But that’s not what Von Drehle sees President Donald Trump providing.

“What I missed over the past week was that,” Von Drehle said. “And … there’s a growing feeling that I have in watching President Trump that makes me question whether he’s happy in the job and wants to do it.”

But what, Gibbs wanted to know, does this mean for the media?

“One of the things presented by Charlottesville that we all hear is that by covering an event like this in the way that we have, by putting microphones in front of white supremacist protesters, that we are giving them a platform,” Gibbs said.

Von Drehle responded that the idea of the press “filter(ing) the American experience” made him “very uncomfortable.”

“It’s not our job to decide what the country should be or to decide where the country should go; that’s the job of the American people,” he said. “It’s our job to try to provide them with information to help them make the choices that they are called on to make.”

By being open, inquisitive and fact-based, Von Drehle argued for a mode of journalism that contextualizes rather than editorializes.

“If you tell me that there were 500 or 1,000 neo-Nazis gathered from across the nation of 330 million people, that makes me less worried than if I think that this could be happening in my neighborhood next week,” Von Drehle said.

There are forces who are incentivized to make hatred seem more prevalent than it actually is, he added, and it is the journalist’s place to resist their influence and provide an objective sense of scale.

How much is the world going to be changed by supercomputers in the palms of our hands; the ability of every person on the face of the Earth to become their own media producer, their own media aggregator, their own managing editor for their own mindspace?” David Von Drehle asked. “So that’s the background of Charlottesville.”

Meanwhile, Trump’s seemingly self-destructive response to the events in Charlottesville was a wrinkle unto itself.

It reminded Gibbs of an Time article Von Drehle had written in January 2016, before any primaries had actually taken place. The cover read: “How Trump Won.”

“It talked about (Trump’s) understanding of how the media works, and what he had already accomplished,” Gibbs said. “Which, of course, knowing what we know now, and what we even have seen in just the last five days, is even more confounding, surprising, unprecedented.”

The term Von Drehle chose to describe the Trump phenomenon — “disintermediation” — comes from Palo Alto, not D.C. But the process it describes, the removal of middlemen, is now just as relevant inside the Beltway.

And though the political establishment also found itself cast by the wayside, it was perhaps the mainstream media that Trump disintermediated the most.

“(Journalists’) traditional screaming function where we say that, ‘This has gone too far,’ that ‘That is too much’ — that used to mean something,” Von Drehle said. “And it became rapidly clear to me that it meant absolutely nothing.”

Trump had spent decades building a base, so he was able to bypass the traditional gatekeepers when running for office. And his brand, bristly and impulsive and decisive as it was, served as not a handicap but an asset.

“It’s very hard to persuade a person who is in the end zone that they don’t know how to score a touchdown,” Von Drehle said.

But though Trump may not have needed the media’s support, he placed a high premium on its coverage. Von Drehle recalled a surreal experience he’d once had watching Trump flip through the TV channels on his plane; just a candidate at the time, Trump was already being discussed on every single one.

“When (Trump) turned to me to explain what I was seeing, I mean, he hit the nail on the head,” Von Drehle recalled. “He said, ‘See, David, this is what it’s all about: ratings. Ratings are power.’ ”

The fallout of Charlottesville, and Trump’s attempts to place himself in the middle of the national dialogue, makes that power all the more relevant.

As a member of the press, that dynamic raises an important question for Von Drehle: “Is it going to be good for us, in the long run, to have our agenda driven every day by President Trump?”

For instance, in June, the White House assigned each week a topical area of policy it would focus on; but as Gibbs noted, the press got criticized for not covering the substance of those issues, instead prioritizing Trump’s tweets.

“Do you cover what the president thinks is important … or do you cover what arguably concretely affects many more millions of people’s lives?” Gibbs asked.

Then again, Von Drehle noted, the rift between policy and messaging is one that Trump has deliberately opened.

And with smartphones offering unprecedented access to information for the everyday citizen, people are more empowered than ever to educate themselves on the issues — but only if they so choose.

“The communication revolution, just as it disintermediates the power from the middlemen, it’s distributing that power to the individuals,” Von Drehle said.

The age of Walter Cronkite is over, and it isn’t coming back. People now have a choice for themselves: to engage with the other side or to withdraw into self-congratulatory ideological silos.

That isn’t to absolve media institutions of responsibility for their failures, though.

“The media was accused of over-covering (and) miscovering the campaign and this administration, and at the same time, got it wrong, missed history,” Gibbs said.

What went wrong?

Part of it, Von Drehle said, is that outlets are incentivized to publish quickly, and if not quickly, then provocatively.

“If you’re chasing the shiny object,” he added, “you’re going to miss the important stuff.”

At the same time, the circumstances surrounding Trump’s election were unprecedented. And since political journalism relies on historical trends, an event that bucks those trends throws the system into disarray.

“2016 was a new thing, and we kept applying the lenses of the past to say what could happen,” Von Drehle said.

The result was a set of predictions that strayed far from reality.

“I remember that phone call,” Von Drehle said, thinking back to election night. “You said, ‘Uhhh, I don’t think we have the right (Time) cover.’ ”

(Journalists’) traditional screaming function where we say that, ‘This has gone too far,’ that ‘That is too much’ — that used to mean something,” David Von Drehle said. “And it became rapidly clear to me that it meant absolutely nothing.”

Now, post-election, America seems to be a place of contradictions.

On one hand, Gibbs noted, is the pessimist’s view: This is an age of “American carnage” and “diseases of despair,” economic struggles and spiritual weights.

On the other is the optimist’s: It’s an age of “extraordinary technological innovation” and “the longest uninterrupted period of peace since the Roman Empire.”

Von Drehle, who once took the wearier worldview, now leans more toward positivity.

“To me, the most striking and baffling thing going on in the United States right now is the cloud of pessimism that’s hanging over this country,” he said. “As I go through my life and my reporting and my work and my reading, I just don’t see the objective basis for it.”

Change, yes; doom and gloom, not so much.

Economic dislocation, for instance, is not a new phenomenon. Small-scale farming, and all the struggle it entailed, is no longer a major factor in America. Neither is the danger of coal mining, nor the mind-numbing grind of assembly-line labor.

“I think we’re going to survive that, you know?” Von Drehle said. “I don’t know what it’ll look like, but we’ve always thrived. And that confidence is just completely missing from our conversation.”

This is so strange, he added, because the space for a political movement grounded in optimism is currently unclaimed.

Wrapping up their dialogue, Gibbs tied it all back to the week’s theme.

“What would you say you’d like (the press) to do, individually and collectively, to restore trust in journalism?” Gibbs asked.

Certain traits — humility, introspection, transparency — will be vital, Von Drehle said.

But open-mindedness is particularly important.

“There are plenty of journalists who have bully pulpits (and) who are at a point in their lives or careers where nothing that could happen, or be said, or be done, would change their minds about anything,” Von Drehle said. “That to me is not journalism.”