- Around 90 acres were covered in the application of three herbicides on June 11 and 12 in the towns of Busti, North Harmony and Ellery.

- Two species, Eurasian watermilfoil and curlyleaf pondweed, were the targets.

- Chautauqua Utility District will be doing increased testing on the water going into the summer season.

- The buffer zones for recent herbicide application were more than three times the minimum distance required by the federal government.

- The Institution’s priority has always been safety of the drinking water.

In the 134 years since Lewis Miller and John Heyl Vincent laid the groundwork for what would become Chautauqua Institution, the lifeblood has remained the same. Chautauqua Lake provides the backdrop, the resources and the environment upon which the Institution and county have stood and grown to this day.

But with that growth comes problems.

An excess of phosphorus and nitrogen due to runoff and loose soil in surrounding areas over many years, introduction of invasive and foreign species and plant life, and other factors have impacted the lake’s current health. The build-up in phosphorus alone has earned the lake an official label of “impaired” from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

Chautauqua Institution President Michael E. Hill acknowledged that.

“While if we did nothing or more of the same, the lake might be on a worse trajectory, I think there’s been a consciousness raised that if that lake ever did ‘die,’ it’d be catastrophic to the areas around it, to the Institution, to property values,” Hill said. “And so we’re keenly aware and sensitive to that.”

Weed Management

John Shedd, vice president of campus planning and operations, pointed to the Institution’s history as stewards of the lake. In response to the lake’s “impaired’ health, the Institution has developed stormwater management programs, planting rain gardens and installing permeable pavement in numerous locations across the grounds, all to protect soil eroding into the lake, and to prevent the runoff of pollutants like phosphorus and nitrogen into the water.

And, Shedd said, the Institution has data that there’s been significant reductions in those pollutants as a result of those projects.

“The Institution feels they have been become a model community for waterfront management,” Shedd said.

But increases in harmful and toxic algal blooms, and density of milfoil weeds and other macrophytes within the south basin of the lake, resulted in calls for stronger action to address the issues.

Those calls for strong action led to May 25, when the NYSDEC granted permits to the towns of Busti, Ellery and North Harmony for the use of herbicides in the control of macrophytes (plants, typically aquatic, large enough to be seen by the naked eye) in Chautauqua Lake, according to a letter of notification the Institution received in June.

The DEC supervised a 30-acre herbicide application test near the Town of Ellery/ Village of Bemus Point in 2017 as a Data Collection Project, after requests from the Chautauqua Lake Partnership.

The CLP, a local non-profit organization, aims to address buildup of weeds and algae that can create nauseating odors and affect the swimming, fishing and other recreation around the shoreline and lakefront properties, according to the organization’s website. Current weed management methods on the lake handled by the Chautauqua Lake Association have not been effective enough, according to the CLP.

Herbicide Application

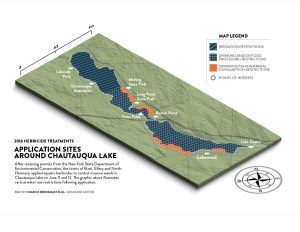

Ellery operated as the lead agency in acquiring the option for application of the herbicides upon completion of an updated Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) this spring. The DEC granted permits for herbicide use on 191 acres of the lake over eight of the 11 proposed treatment sites.

Around 90 acres were eventually covered in the application on June 11 and 12 in the towns of Busti, North Harmony and Ellery, according to The Post-Journal. Six areas were impacted along the shoreline of Midway Park, Sunset/Warner Bay and Bemus Bay in the town of Ellery, the town of Busti and shorelines of Bly Bay and Sunrise Cove in the town of North Harmony. This is the only application planned this year.

The lake management company SOLitude handled the application of herbicides on the lake, supervised by the DEC.

Those chemicals often have variable results, with increased variability when applied more frequently, according to a 2017 study conducted by scientists in the Bureau of Science Services of the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources.

Additionally, those herbicides may actually increase harmful and toxic algal blooms on the lake. Becky Nystrom, a biologist and conservationist at Jamestown Community College and co-founder of the Chautauqua Watershed Conservancy, expressed concerns in an Ellery public meeting in late December last year that the decomposition of the plants would likely release nutrients, enhancing the algae growth in the lake.

The second main area of concern is the Navigate being applied into the lake. The herbicide contains components deemed a carcinogen by the World Health Organization. Two communities, Chautauqua Institution and Chautauqua Lake Estates, draw their drinking water from the lake.

Former head of the Chautauqua Utility District Tom Cherry shared his concerns about the chemical being ingested in the same town meeting. The Institution, which Cherry estimated uses around 600,000 gallons of water a day, has no way of filtrating these toxins from the water and would not be able to detect them until they had already been in the system for two weeks.

“If we contaminate the system, it will have to be decontaminated — which is another process, the distribution system, and I don’t know if you know this, but I’d have to shut the system down,” Cherry said according to meeting minutes. “That means we’ve got 10,000 people without any water or fire protection until all of this work is done.”

Michael Starks, current superintendent of the CUD, will be doing increased testing on the water going into the summer season, according to Hill and other Institution executives. The testing will be examined at DEC-certified labs. It is unknown when results can be expected.

The recent herbicide application buffer zones were more than three times minimum amount required by the federal government. The concentration of Navigate would not be harmful to human beings swimming or drinking the water, Hill said. Still, he said, the presence of the chemical remained a rallying cry for the Institution — a sentiment Shedd echoed.

“It was a dealbreaker in us being able to support or be a part of the solution,” Hill said. “It is still our hope that it not be used in the future.” The Institution has hired both legal and scientific teams to closely monitor the situation, and increased testing leading up to the start of the season to ensure the safety of the water, Hill said. Experts created models for lake currents and flow, deciphering under what conditions chemicals could reach this area of the lake basin. Hill said the odds are “significantly” unlikely that anything could reach this area of the lake, barring a “freak event of nature.”

Shedd said he and other members of Institution administration have “taken a lot of time becoming immersed and analyzing the situation.”

The Institution has been deeply, if quietly, involved in the process, he said, citing the hiring of the legal and scientific teams — “different scientists around the lake who have acted with us as stewards, trusted stewards of the lake,” Shedd said. “When this whole issue of putting herbicides in the lake came up, it automatically raised red flags: ‘Is this being done right?’ ”

When Institution concerns about the application were not addressed, the focus shifted to risk mitigation, Hill and Shedd said.

Hill said the priorities have always been simple: first, the safety of the drinking water and overall lake health, in addition to recreation on the lake.

The Institution has said that the use of herbicides safely away from the drinking supply, if supported by scientific evidence, could be one part of a comprehensive solution, according to Hill. A large problem he discussed was that it seemed each organization involved in the issue had its own set of science, data and opinions.

A need for consensus

A strong partner in the Institution’s stance on the issue has been Chautauqua County Executive George Borrello. Hill said Borrello has been helpful as the issue progressed in recent months, acting as a mindful moderator.

“The prescription is to treat the disease and not try and manage the symptoms,” Borrello said. “The public side of this is managing the symptoms, unfortunately.”

The Chautauqua County government has made progress through land management and flow from farmland and stream banks in recent years, Borrello said, and a big step has been addressing the ailing septic systems around the lake.

A few years ago, it became mandatory that any septic tank within 250 feet of the lake be subject to inspection. The county found that about half of the systems around the lake were failing, or had failed in the past. This contributed to a heavy manmade flow of nutrients into the lake.

“We need to find consensus and a common ground,” Borrello said. “What we’ve lacked is true collaboration from both sides to see if there is some common ground. I believe there is.”

Borrello believes the responsible use of herbicides is part of the long-term solution for the issues facing the lake, but said more collaboration and confirmation with research and evidence is necessary to ensure the safety of everyone, especially those who draw their drinking water from the lake.

Borrello said he believes the people in favor of the herbicide application have been aggressive, rather than waiting to hear from the other side to avoid risks or possible litigation. The county’s role has been to be the “adult in the room” in these discussions, Borrello said.

“Just because you think you have the majority opinion on your side, doesn’t mean you won’t face serious litigation,” Borrello said.

Borrello has been disappointed in strong-handed actions from both sides, not just the CLP, but also recent actions from the CLA as well. There are extremes on both sides, and force feeding opinions is never the way to achieve consensus, Borrello said.

A recent article from The Post-Journal discussed recent census estimates that show a population decrease in the largest areas of Chautauqua County. The CLP has used this, as well as decreasing home values and tourism, as evidence of the lake’s poor health in its efforts to build support for herbicide use. Borrello dismissed what he labeled as “misrepresentations” and “rumors” that tourism and property values were declining.

He cited increased sales tax revenue in the county, and mortgage recording tax being the best it’s ever been. A planned $40-million resort hotel in Celoron being built, the largest of its kind in western New York, is proof people still want to come to Chautauqua Lake, according to Borrello.

“We need to take a pause and say that’s not the reality, that’s the perception,” Borrello said. “When people speak in generalities, it’s always better to respond with specifics.”

Doug Conroe, executive director of the CLA, has been spearheading efforts in recent years to manage and deal with the vegetation and scum removal on the lake. Conroe, who personally implemented the largest herbicide treatment on the lake in the late 1980s and early 1990s, said that although there is a time and place for herbicides, this is not it.

“The warning signs essentially say don’t use the lake for irrigation all summer,”said Conroe, who previously served as director of operations at the Institution.

“Personally I think if (Navigate 2, 4-D) was used far enough away, it probably won’t be a risk. But that’s probable. Why do we want to take on a risk that we don’t need to take on?”

Many of the areas facing issues with irrigation limitations include Chautauqua Golf Course and the local fish hatchery, as well as the Institution. Conroe said he is confident the CLA could meet the lake’s needs with expanded resources and funding. The test treatment done by the DEC in 2017 provided the same services the CLA would have provided, Conroe said, but at over five times the cost.

The CLA operates from three locations on the lake with three crews, working with harvester vessels, transport barges and dump trucks to manage weed harvesting and debris removal. Conroe said the CLA does not have the funds to keep all of the equipment in use, only operating five days a week.

“If we are funded properly, our harvesters can meet the plant management needs,” Conroe said. “We could take those machines out of dry dock, work more days. We could control the lake the way it needs to be controlled and there’d be no risk.”

Conroe said people are learning the risks of chemicals, such as DDT, that were once thought to be safe in the past. Today, it is clear they are unsafe. It is lack of water flow studies and flow/ dispersal models that leave a lot unclear, Conroe said. An unusual presence of easterly winds around the lake this time of year carry currents typically going south westward, which makes predicting the dispersion of those chemicals unclear.

A need for communication

Conroe said a collaborative strategy does exist and is alive and well. He said a strong push for immediate results from certain groups has set back efforts and public understanding by 20 years.

The CLP did not respond for comment on the herbicide application, and a representative of NYSDEC declined an interview.

Strong support from the Institution and Chautauquans have helped make a difference, Conroe said. He has concerns that the economic status of county residents will be detrimentally affected if the lake can not bounce back.

Shedd said he has been concerned with the poor communication and processes of the DEC and CLP. Shedd, who lives in Lakewood, said his concerns began when the Institution received no notice of the testing done in Bemus Bay last year until signs were posted around the beaches of the Institution that said not to swim.

“Why didn’t anyone tell us this?” Shedd said. “They (signs) just showed up. We had guests that are here to go swimming, and can’t use the lake. Are you kidding? This is the busiest time of the season.”

This year, Shedd and other Lakewood residents raised concerns after the herbicide application when vessels involved in the process were spotted near their shoreline where herbicide application was not approved. The Lakewood community is currently waiting on results to see if herbicides were in fact dispersed in the area. Shedd said he doesn’t have a timeframe yet for when results will be received.

A potential ‘success story’

Hill was adamant that going into the 2018 season, the Institution’s drinking water is safe.

“I live on the grounds and drink the water everyday, and I’m fine,” Hill said. “We will continue to monitor it and test. We’ve been really transparent through the whole process, and we’ll continue to do that.”

As leader whose responsibilities include stewardship of the lake, Hill is optimistic about the future. He cited a strong push, alongside the county and other organizations, in receiving significant funding from New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s recent $65-million action plan to aid 12 priority waterbodies in the state, including Chautauqua Lake.

“If we can get the right coalition of people together, this can be one of the great success stories in New York,” Hill said.