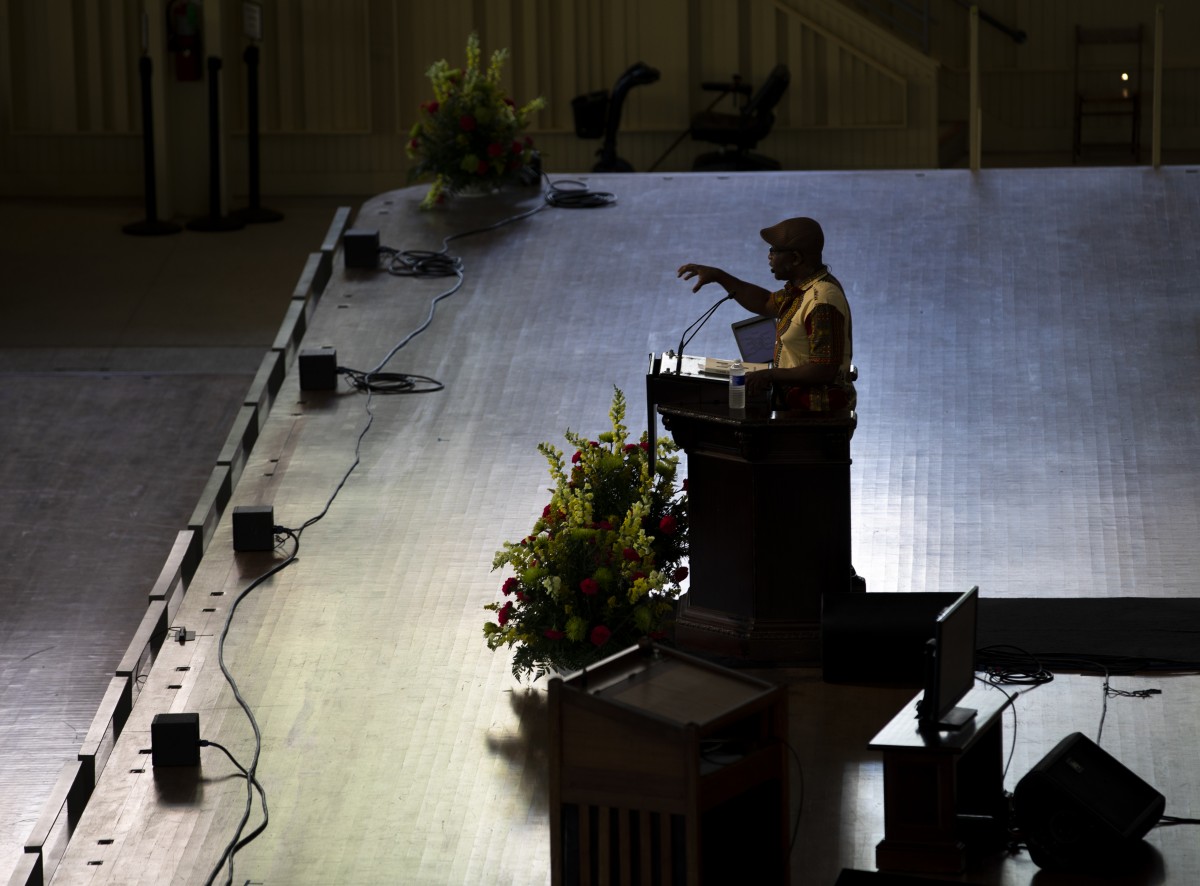

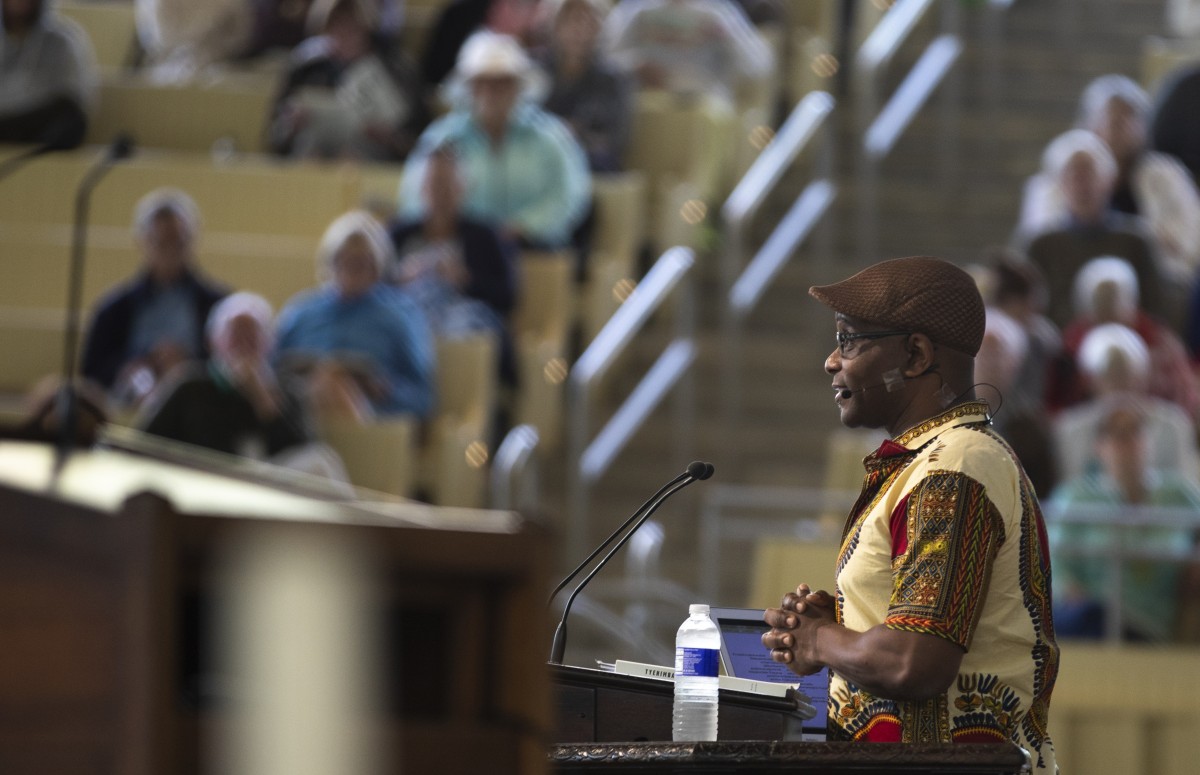

Tyehimba Jess brought the written word to life.

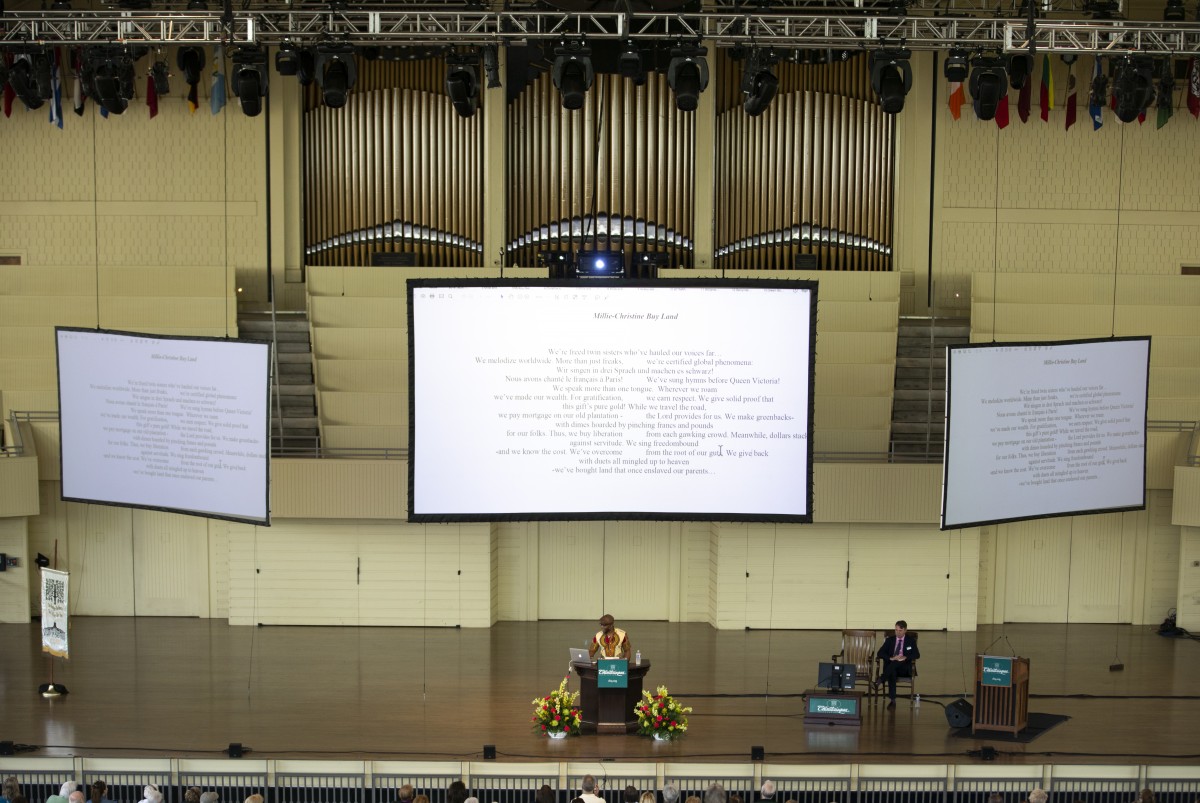

The accomplished poet highlighted his unique — and crafty — style Tuesday, June 26, in the Amphitheater for Week One’s second morning lecture and the first Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle Roundtable.

An award-winning slam poet turned author, Jess’ first book of poetry, Leadbelly, won the National Poetry Series competition in 2004 and was hailed one of the “Best Poetry Books of 2005” by Library Journal and Black Issues Book Review.

Jess’ most recent work, Olio, won awards such as the 2017 Pulitzer Prize, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award and The Midland Society Author’s Award in Poetry.

The word “olio” describes a mixture of “heterogeneous” ingredients; in historical and the book’s context, “olio” refers to the middle of a minstrel show.

“Minstrel show is a form of entertainment started in the 19th century which consisted of white performers putting on blackface and tattered clothes in order to make caricatures of African-Americans,” Jess said. “It was principal for a form of psychological warfare that continued throughout the 19th century and into the 20th century and still manifests today.”

Jess pointed out a book — “a handy dandy guide for how to put together a minstrel show.” The first entry was titled, “How to Black Up.”

Olio centers on African-American artists and creators, an interest spawned from Jess’ curiosity about the origin of black music, he said.

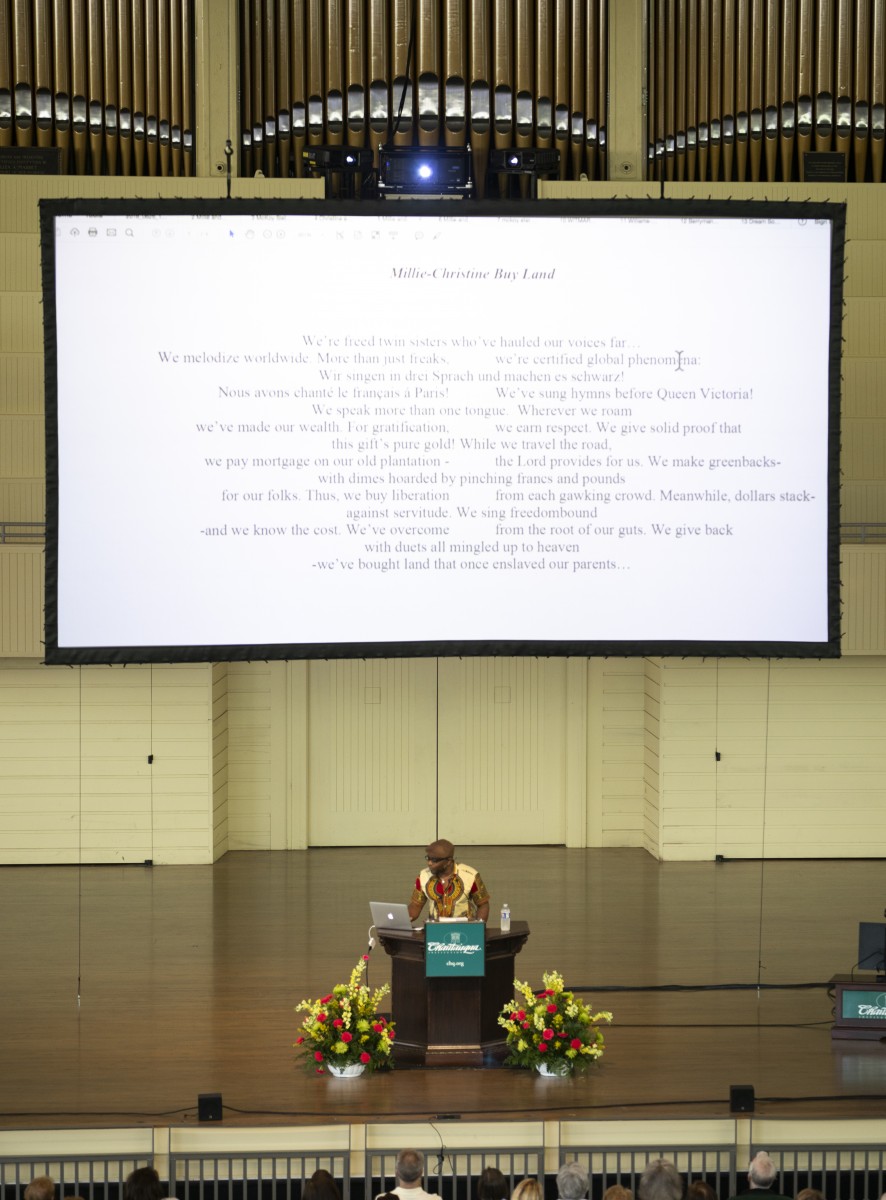

Millie and Christine McKoy are Jess’ subjects for five pieces in the book.

The McKoy women were conjoined twins, fused back-to-back from the base of the spine to the tailbone. The two were born into slave-state North Carolina in 1849 and their master sold them to the circus at 18 months old, according to Jess.

“The twins did not just stand and get gawked at,” Jess said. “They sang — duets of course.”

Jess’ first poem about the twins — “Millie and Christine McKoy” — is written, and can be read, in three parts. The first from the perspective of Millie runs down the left of the page; Christine’s voice runs down the right. Their united voice runs through the center.

“We’re fused in blood and body — from one thrummed stem/ budding twins blooms of song,” Jess read down the center. “We’re a doubled rose…”

Jess moved to read Millie’s side:

“We’ve mended two songs into one dark skin / bleeding soprano into contralto…”

Then from Christine’s side:

“We ride the wake of each other’s rhythm/ beating our hearts’ syncopated tempo…” he read.

Jess finally blended the three columns and two voices, reading:

“We’ve mended two songs into one dark skin / we ride the wake of each other’s rhythm/ bleeding soprano into contralto/ beating out hearts’ syncopated tempo / — we’re fused in blood and body — from one thrummed stem, budding twin blooms of song. We’re a doubled rose…”

Olio is structured to give the reader flexibility.

“The reader can choose any path they want in these poems — I just make the decision as I go through about which way I want to go,” Jess said.

This line of continuity runs through each poem and even onto the cover, which spells “olio” from the left, right, up and down.

Following “Millie and Christine McKoy,” Jess read a poem titled “Millie-Christine: On Display.” The piece cries out in response to “egregious damnation,” Jess said, to which the McKoy women were subjected, forced to expose themselves to prove they were conjoined.

Again, the middle of the poem reads as the twins’ conjoined voice:

“We count the blessings of our doubled shell / as we pay our dues. We’ve proven ourselves / for science. We’ve been taken town to town / like prize bovine: We’ve been pawned up and down / each sawbone has searched us from spine to loin / our wondrous one- ness exists. We’re conjoined / We’re not frauds, but born of providence / God mended two souls into one dark skin,” Jess read.

Jess demonstrated the flexibility by reading the poem backward, adding in lines from the left and right sides, both Millie and Chris- tine’s voices.

In the next piece, Millie and Christine have been kidnapped and taken to Britain to perform, forcing their mother to choose between the United Kingdom, which had abolished slavery, and “Dixie’s rebellious mouth.”

Their mother ultimately chose the South.

The McKoy twins were able to profit from their act and eventually buy the plantation on which they were once enslaved. Jess jumped from line to line in the poems, skipping and repeating phrases, owing from one stanza to the next.

The final piece, a star- shaped poem, merged each of the prior poems and featured repeating lines throughout.

“A star of syncopated sonnets — because the McKoy twins were stars right?” Jess said over murmurs of awe from the crowd.

The final sonnet’s features mimic that of its subjects — not only a star, but two heads, a conjoined middle and two bases. The son- net can be read in infinite combinations, Jess said.

“Whichever direction you want to go with your eyes, tracing across the bottom of the poem in the same way that the gawker’s eye traced across the body of the McKoy twins,” Jess said. “Except in this case, you are taking the story of the McKoy twins and you are getting involved in their story and not just looking at their body.”

Jess also shared the story of Bret Williams and George Walker, comedians he described as the “Key and Peele of their generation.” His piece is a dialogue between the two men.

“There’s a coherent relationship between the right and the left side,” Jess said.

He, again, jumped and repeated lines, demonstrating the poem’s flexibility and how the connotation changes with every combination of lines. Each line of the poem can be paired with any of the five surrounding it, Jess said.

“… believe the human / might be saying ‘Look at that handsome man!’ Nobody/ might be saying, “Look at that handsome man!’…” Jess read.

After Jess finished “Brett Williams / George Walker Paradox,” he grabbed Olio, moved in front of the lectern and ripped the page from the book’s spine. He began folding the page to reveal new combinations of the poem. He brought the edges together to form different cylinders; with a fold and a twist he created a Möibus.

“I want the reader to deconstruct the book in order to reconstruction the people inside the book,” Jess said.

After the lecture, Vice President and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education David Griffith opened the Q-and-A with a question about Jess’ transition from slam poetry to prose.

Jess said competitive slam poetry taught him how to engage with — and keep — an audience.

“The harder you work on the page, the less you have to work on stage,” he said.

Griffith then turned to questions from the audience. One attendee asked about the reasoning for the church names that line each of Olio’s pages.

Lining the pages with the names was inspired by activist organization Black Lives Matter’s practice of repeating the names of those killed by police, as well as the lack of tribute to black churches that were burned down in the 19th and 20th centuries, Jess said.

A year prior to Olio’s publication, nine people were shot and killed at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. To Jess’ surprise, that church had also been burnt down decades earlier; it became the first and last church listed in Olio.

The final question asked whether Jess has or would write poetry about the current political climate — echoing a similar theme from Monday’s conversation with John Irving.

“All kinds of things happen around the word that deeply trouble me, and I think what I’m writing about now answers or corresponds with what’s happening the world today,” Jess said.