At 17 pages, Nicole Cuffy’s bildungsroman covers more years in her protagonist’s life than there are leaves in her book.

Cuffy’s work, Atlas of the Body, is the inaugural winner of the Chautauqua Janus Prize, named for the Roman god of duality who simultaneously looks to the past and the future.

Cuffy’s work, Atlas of the Body, is the inaugural winner of the Chautauqua Janus Prize, named for the Roman god of duality who simultaneously looks to the past and the future.

A reception will be held at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, July 25, in the Athenaeum Hotel Parlor, followed by a book signing.

Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, said the reception will be a celebration mirroring the spirit of the prize, trying something both fun and new: The George Burton group will provide the jazz and Janus the inspiration for the evening’s signature cocktail.

The Janus Prize recognizes short works of fiction or nonfiction that experiment with form and disrupt convention in a way that is new, challenging and unexpected, but also accessible.

“In its very innovative strategy, it’s capable of creating a new kind of understanding for the reader of time, of history (and) of future,” Atkinson said.

Kazim Ali judged the prize, selecting Cuffy’s work out of 16 finalists.

Ali is also the Chautauqua Writers’ Center Week Five prose writer-in-residence and will deliver his Brown Bag lecture, “Genre Queer: Notes Against Generic Boundaries,” at 12:15 p.m. Friday, July 27, on the front porch of the Literary Arts Center at Alumni Hall.

“I’m interested in the way the structure of Atlas of the Body is able to expand time and describe how ‘impact’ is not a moment in a life, but something that happens over many years,” Ali said. “Her characters do not behave the way characters in a novel or play do, but the way people in a life do.”

“I’m interested in the way the structure of Atlas of the Body is able to expand time and describe how ‘impact’ is not a moment in a life, but something that happens over many years,” Ali said. “Her characters do not behave the way characters in a novel or play do, but the way people in a life do.”

Cuffy, who comes to Chautauqua for the first time, is an editor at Atomic Theory Micro Press; her work has appeared in Mason’s Road and The Master’s Review Volume VI.

Cuffy said Atlas of the Body originated from an emotion. She wanted to focus on loss and grief in a way that wasn’t “cliche.”

After meditating on the idea, she said the story emerged organically.

“From there, I’ve always been fascinated by anatomy,” she said. “I thought that was just a really good way for me to get into the gristle, so to speak, of the emotions, which was first love, growing up, trying to define what success is, coming out of poverty and grieving.”

Through the anatomy of the heroine, Maya, Atlas of the Body reveals the texture of a life, similar to the rendering of an Impressionist painting.

Inspired by the intersection of the arts, Cuffy’s form breaks from a linear tradition, instead drawing from pointillist techniques. Like dots of colorful paint on a canvas, snapshots of a young woman’s life act as “islands of illumination” that together reveal a whole.

“But you can still see that it’s made up of those little facts,” Cuffy said.

The final portrait became a study of another style: Minimalism.

With more happening off the page than on, Cuffy said she embraced the idea of “giving enough scene to tell the story with really no excess.”

Though short in pagecount, the story melds many of Cuffy’s interests.

In fact, Cuffy said she dreams of creating a “salon a la Gertrude Stein” that creates space for conversation between different types of artists, from the literary to the performative.

Cuffy said she has always been interested in anatomy. Before she majored in creative writing, she toyed with the idea of studying medicine. She incorporates science of the body into much of her work, and writes with a medical student’s textbook of anatomy for reference.

She is also a ballet dancer and certified yoga instructor, which has enhanced her knowledge of the body, particularly the interconnectedness of the mind.

“I would also say that my writing, my style, my process for creating something is kind of what gave me the predilection for yoga in the first place, being really interested in the spirituality, the meditation, and then asana,” she said. “That all kind of fits together.”

Cuffy said this space to explore and experiment with form is vital.

“Literature is one of the fine arts, and one of the things that is so important about art is it evolves as culture evolves. It’s always a reflection of what’s going on in the world. As you, in literature, play with form, you’re creating this reflection … of the world at large.”

-Nicole Cuffy, Author, Atlas of the Body

Cuffy said parts of the story are “deeply personal.”

For instance, in one scene, Maya looks at a photograph of her grandmother as a young woman “that always makes her cry” because the woman in the photograph does not know her future, her “aborted dream of stardom” or the lung that “grows and then devours.”

“Growing up, most of my grandparents had passed away before I was born,” Cuffy said. “There’s something so complicated that happens when you’re looking at an old picture, … particularly when it’s someone who’s tied to you.”

Cuffy knew her grandparents through pictures and stories from her parents. She said there is something poignant about looking at portraits and knowing more than the person in the frame.

“You also have this awareness that one day, someone’s going to look at a picture of you and know way more than you do now about your life,” she said. “It makes you really aware of your own mortality. It’s both really sad and really beautiful; it’s one of those things that makes life so precious.”

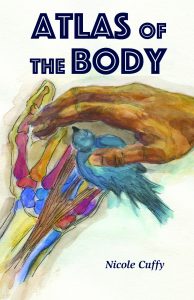

This duality is exemplified in the final pages of the story, when Maya maternally holds a bird fallen from a nest.

“I was thinking about fetal anatomy, and how close a human fetus is to a chicken fetus for quite a while in gestation … but also, in terms of anatomy, I was just thinking about grief and how it’s so tied to loss, but it’s also tied to birth,” Cuffy said.

Though the bird’s future rests in Maya’s palms, the moment is not about the bird, but Maya’s own perch on a precipice.

Like the god Janus, Cuffy said Maya is caught in a moment of in-between, a “nascent (and) fragile state that at the same time is full of potential and full of a future.”