Ori Z. Soltes has never encountered a country as religiously obsessed as the United States, a country that prides itself in its separation of church and state. With one exception: Russia.

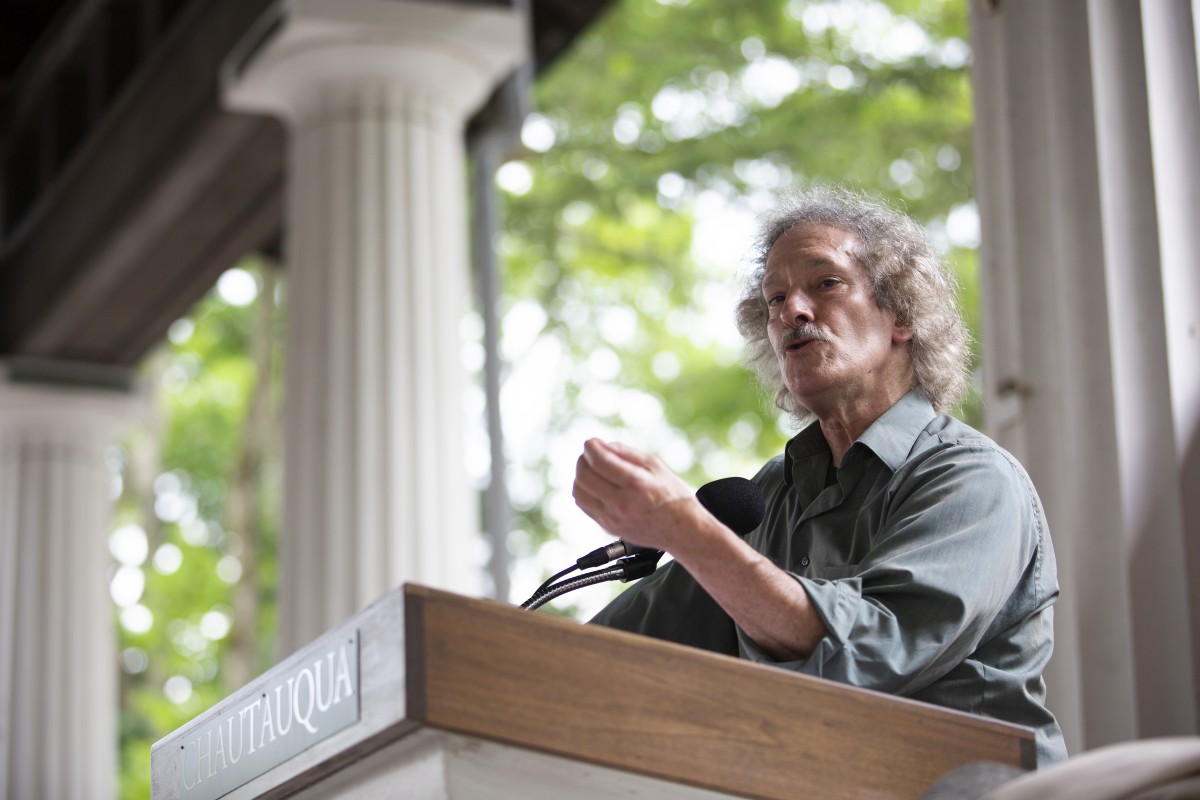

Soltes, a professor at Georgetown University, former director and curator of the B’nai B’rith Klutznick National Jewish Museum and lifelong scholar, gave his first of four speeches as part of Week Four’s theme, “Russia and Its Soul,” at 2 p.m. Monday, July 16, in the Hall of Philosophy, titled “Icons and Identity: The Shaping of Mother Russia.”

According to Soltes, throughout history and leading up to present day, Russia has always been a “bundle of contradictions.”

“It is a place where you will encounter warmth exceeded nowhere else,” he said. “You will also encounter violence exceeded nowhere else.”

This struggle within the Russian sense of identity can be symbolized by what Muscovites originally said of St. Petersburg, Soltes said.

When Peter the Great established St. Petersburg in 1703, it was because he was infatuated with Western Europe and wanted it to become his “window on the west.” However, the people of St. Petersburg said it was almost too Russian to be European and yet too European to be Russian.

“The sense of what we are is even visible, contrastively, in the way (Moscow and St. Petersberg) understand each other,” he said.

This identity struggle appears in Russian language as well.

The country’s primary, and only official, language is Russian, but a law was passed in 1997 permitting groups with different parent languages to be able to teach those other languages.

“You’ve got about 160 different ethnic groups with different languages that they might choose to juxtapose with Russian as the way to go,” Soltes said.

Soltes believes Russia’s history is tied not only to the idea of being Russian in ethnic, linguistic or cultural ways, but religiously as well.

The topic of Russian identity started being explored in the ninth century by Russian archaeologists, paleontologists, art historians and artists working together to imagine the first evidence of human life in the country. What they discovered is that these early people differed greatly from modern-day Russians.

“The problem with this is that they probably were not speaking Russian, and they are probably not Russian Orthodox,” Soltes said. “Who knows who they were; they just happened to be there.”

As it turned out, the first Russian citizens were nomadic, a community of people without fixed habitation who regularly moved to and from the same areas.

“The first viable group that seems to assume a kind of political identity in that area is a group that has come from the Crimea and beyond, known as the Khazars,” he said.

Soltes said there are two things about the Khazars that make the idea of Russian identity and soul “very interesting.”

The first is the fact that the Khazars were Turkic, so in terms of language, they had nothing to do with Slavic languages. The second is that a majority of Khazars converted to Judaism as opposed to Russian Orthodoxy.

Regardless, the Khazars were pushed out of the area by a Germanic group from the north, otherwise known as the Vikings. Their leader, Rurik, established himself in Kiev and Novgorod.

“So, in the late ninth and 10th centuries, that central area is dominated by a group that is probably not Slavic, but Germanic,” Soltes said.

The reason for Soltes’ uncertainty is that if there was an indigenous population in Russia at the time of the Germanics, they would have been “a Mediterranean or Middle Eastern sort.”

“They would be dark-skinned, (have) dark hair, dark eyes, and this group coming from the north probably has light skin, redish, blondish hair and bluer eyes,” he said. “So what is it that creates the ethnicity that we are talking about when we are talking about Russia from its beginning?”

According to Soltes, even Russian President Vladimir Putin would have to admit he does not know the answer to the question of Russia’s original ethnicity.

In addition to ethnicity, the beginning of present-day Russia can be associated with the arrival of groups sent from Constantinople to try to evangelize and civilize the Slavs, Soltes said.

These groups developed the Cyrillic script, a writing system used for various alphabets across Eurasia. It is based on the Early Cyrillic alphabet developed at the Preslav Literary School in the First Bulgarian Empire.

“The significance of this is not only that we see the presence of Christianity actively now on the scene,” Soltes said, “but we are reaching the point where we can actually find stuff to read that might tell us what is going on, as opposed to just imagining from archaeological remains, oral stories or visual arts.”

In 988, the Kievan Rus’ established the largest polity in Europe, and the people embraced Christianity as their official religion. Church and state became a unified concept. The acceptance of Christianity would mean that going forward, any definition of what it means to be Russian would have to include religion, Soltes said.

Soltes said what people need to realize is that Kiev is part of Ukraine, so the beginning of Russia was actually Ukraine.

“For those of us who insist that there is a such a thing as ethnic purity, guess what?” he said. “You’re wrong.”

As religion in Russia continued to develop in the 11th and 12th centuries, so did iconography.

“(Iconography) is all about symbolic language. It is the language of intermediation between this reality and that other reality, the Divine reality, in which these figures function as interceptors.”

-Ori Z. Soltes, Professor, Georgetown University

By the 1230s, the Mongols were invading Russia, and Kiev was destroyed by 1240.

“The center of Russian being had to shift, for defense purposes, away from where the Mongols could still continue to attack, north toward Novgorod,” he said. “Novgorod pretty much becomes the political and spiritual capital.”

In the 13th century, Novgorod developed its own school of icon making known for its rich colors and attenuated figures.

One example of an icon created during this time was “The Trinity,” by Russian painter Andrei Rublev. It is his most famous work and the most famous of all Russian icons. It is regarded as one of the highest achievements of Russian art, Soltes said. “The Trinity,” now referred to as “The Holy Trinity,” depicts the three angels who visited Abraham and Sarah to inform them that they would be having a child. The importance placed on icons and symbolism then became a way to differentiate between new and old believers of Russian Orthodoxy.

For instance, old believers only recognize a baptism where the whole body is submerged three times. New believers are “willing to sprinkle some water on you and say you’re done,” Soltes said.

Jumping to the 18th century, a time when Romantic nationalism is at its apogee across Europe, there was a group of students at the St. Petersburg Academy of Fine Arts who questioned why their senior painting was to be of the gods of Valhalla. They considered the topic to be “Norse mythology” and decided to withdraw from the school.

The students then established their own group over the course of seven years. They went to various locations in Russia to paint the landscape and the people. One of those students was Isaac Levitan, the painter of “The Silent Monastery,” Soltes’ personal favorite.

“Aside from the religious emphasis (in the painting) is the way in which, in symbolic terms, the monastery world is that intermediary between us and God,” he said.

To conclude, Soltes touched on the concept of “Holy Russia” that arose during the 19th century.

“It was all about the identity of Russia as a scared territory, understood in very distinct Christian terms, in fact, specifically Russian Orthodox Christian terms,” he said.