What’s the secret to happiness after 50? Arthur Brooks knows.

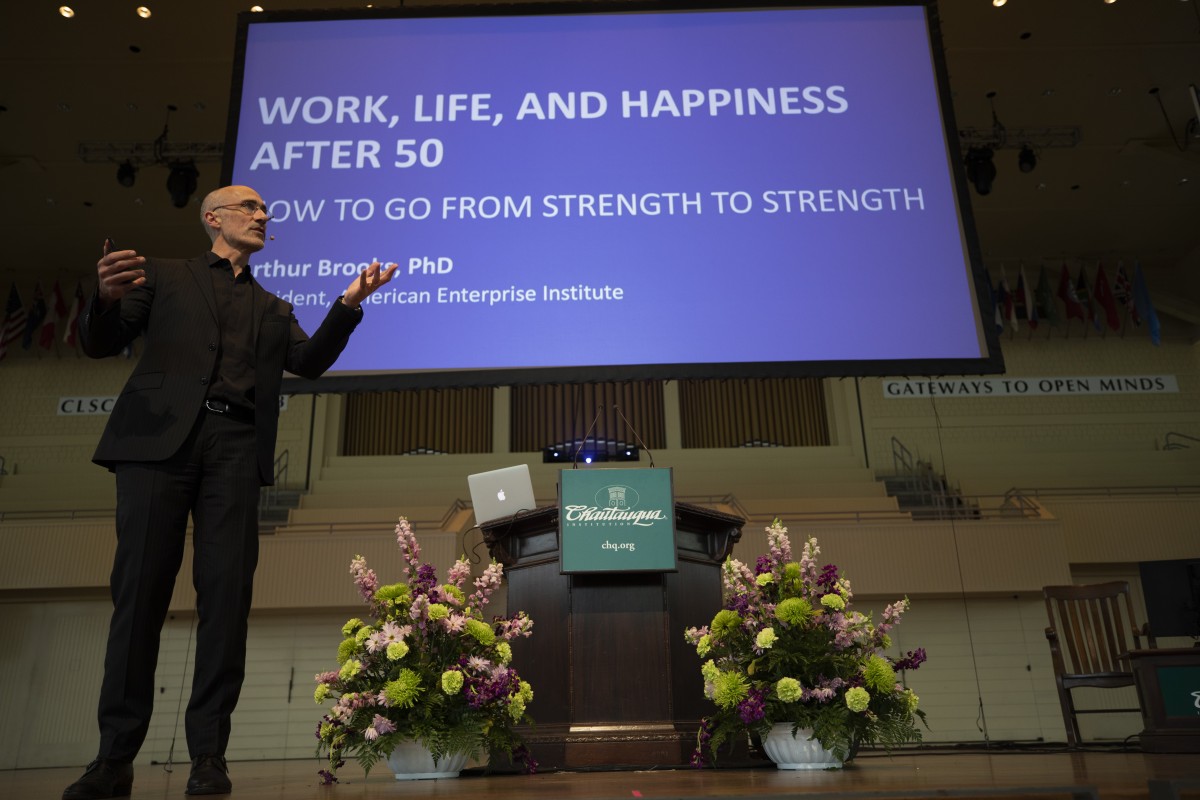

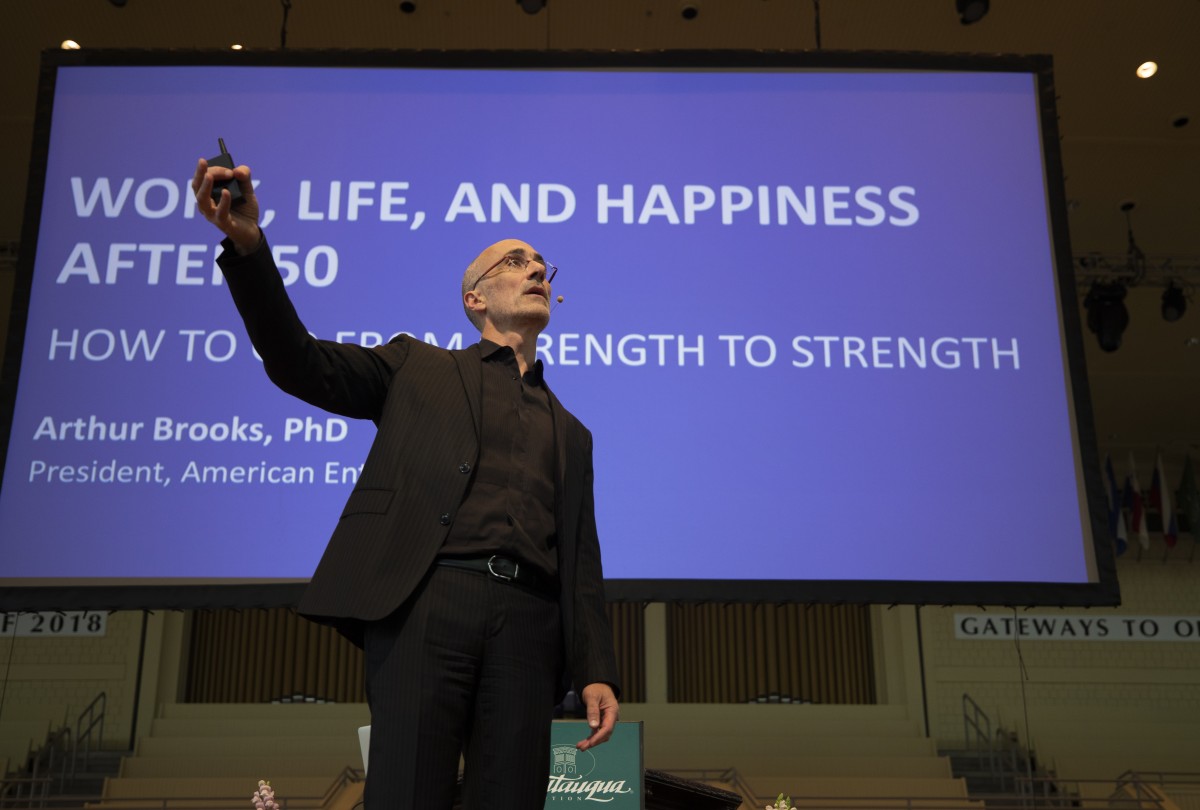

The 54-year-old economist, author and president of the American Enterprise Institute spoke to just that at his 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Friday, Aug. 3, titled “Work, Life and Happiness After 50: How to go from Strength to Strength,” closing Week Six’s theme, “The Changing Nature of Work.”

Brooks’ quest to find the meaning of happiness after midlife began on a United Airlines flight from Los Angeles to Washington, D.C., when an older couple started animatedly arguing mid-flight. The conservation, which Brooks couldn’t help but overhear, went like this:

“Mumble, mumble, mumble,” from the husband, to which the wife replied, “Oh, don’t say that nobody cares about you, that you have nothing to add anymore.”

“Mumble, mumble, mumble,” uttered the husband; “Don’t say it would be better if you were dead,” the wife blurted.

Eventually, the conversation stopped. The plane descended, and while disembarking from the plane, Brooks caught a glimpse of the distraught man — he was a celebrity, an “American hero,” as Brooks described him. Brooks wondered how a man so revered could fall into such dismay. Brooks said he selfishly thought to himself, “How can I not end up like that? … How can I, after a life of some accomplishment, wind up happy and not disappointed?”

Statistically, happiness decreases steadily in the first half of life — hitting rock bottom at 53 years old.

Social psychologists contribute this to three factors, Brooks said: failed expectations, biology and, quaintly put, “family complications.”

“That’s secret code for ‘teenage kids,’” he said. “Now, everybody knows that kids bring meaning, kids bring purpose, but it’s hard and when they are adolescents, it’s even harder. I remember looking at this data, soulless and desiccated numbers on a spreadsheet, and I decided I wanted to give you the best data I have ever seen on the midlife slump … my son, Carlos.”

Specifically, his son Carlos’ YouTube channel, and a video where Carlos attempts to get a job but forgets to put contact information on his resume. Brooks reminisced on when his son was 8 years old, and it was unimaginable that he would move out — 10 years later, it’s an “emergency.”

The good news is that after 53, happiness surges, Brooks said. This spike continues through the 60s, but at 70, the data splits; half experience rising life satisfaction, the other half see the opposite.

So how does one stay on the rise, not the decline? Brooks referenced the man he overheard on his crosscountry flight: high-achieving “American heroes,” seemingly dissatisfied with their lives — that’s who tend to trend on the lower half, Brooks said, because of the burden of the high achievers.

He said those who are successful, career-oriented people are statistically unhappy after their careers end. Brooks used Charles Darwin as an example. Darwin was a rich, famous, world-renowned naturalist, geologist and biologist whose research made him a European hero, Brooks said. But when Gregor Johann Mendel started his work on genetics, Darwin’s contributions became obsolete.

“Charles Darwin fell in adeep depression that lasted the rest of his life because decline happened to (him),” Brooks said. “High achievers suffer the most, why? Because they have the farthest to fall. It makes sense, doesn’t it? If you don’t do anything, you don’t have anything to come down from. But there’s the physics of success: what goes up, must come down.”

Brooks himself knows decline. At 19, he dropped out (or was kicked out, but that’s splitting hairs, he said) of college to pursue his passion — the French horn. At 22, he hit a wall; melodies that were once easy to play became difficult, and difficult pieces became impossible.

At 24, he played in Carnegie Hall, which should have been the height of his professional career. Instead, he fell into the audience while walking to the front of the stage. It was time he literally, metaphorically and physically faced the music.

From there, Brooks got his bachelor’s degree, his Ph.D. and fell in love with his work, which he attributes to a line from poet Dylan Thomas, “rage, rage against the dying of the light.” If he had not stopped “raging against the dying of the light,” he would still be a frustrated French horn player who wouldn’t be speaking for the second time on the Amphitheater stage, Brooks said.

“You’ve got to stop raging,” he said. “Here’s the life lesson: to rage against change delays progress to new phases in life. Ask yourself this: Am I raging? Am I clinging to something in the past? Here’s another question: How can we deal with our change in abilities in a constructive way?”

Intelligence comes in waves during life, Brooks said.The first wave is fluid intelligence, i.e. complex problem solving, working memory and creativity. Fluid intelligence drops off in young adulthood as crystallized intelligence — characterized by accumulated knowledge, experience and wisdom — grows. It continues to grow until death, moving from the “innovation phase” to the “instruction phase” of life.

The instruction phase is when people become teachers, historians and mentors, Brooks said, to share their knowledge with younger generations who are expanding their fluid intelligence, “crowding their brains” and stocking up for the transition to crystallized intelligence.

“Life lesson: Early on, rely on fluid intelligence. … Later, rely on your crystallized intelligence, your wisdom,” he said. “Become a teacher and ask yourself, ‘What am I doing to share my wisdom?’”

Moving away from the stark, abstract theories of psychology and brain science, Brooks looked east.

In the East, he said, art removes what doesn’t enhance its essence, like a jade sculpture carved in stone; its beauty isn’t from extraneous material, rather its absence. This is a metaphor for life, Brooks said — “take away the parts of you that are not you.”

“The whole first part of your life, your success, your happiness, is all about adding stuff,” he said. “More work, more family, more experiences, more relationships, more possessions, but you get to the point where that doesn’t cut it anymore. And the reason for frustration over the second half of life has been that adding a boat doesn’t get you anything. Adding another house gets you nothing.”

To be happy in the later part of life, he said, requires chipping away at unhealthy relationships, kinships and materialism to find one’s true self — “forget your bucket list. Your bucket list should be things you’re going to take out of your bucket.”

But the journey to happiness after 50 is not a solo mission, Brooks said.

“Life lesson: Your true self is not the sum of your achievements — that’s an illusion. It’s the magnitude of the love of the people in your life,” he said. “… That is the essence of being truly alive.”

To close his lecture, Brooks played what he called the greatest artistic ending of all time — Symphony No. 9 In D Minor, the final symphony by Ludwig van Beethoven. Brooks played a clip of the ending, stopping the video before a pivotal crescendo in the music, which might be naively mistaken as the ending.

Instead, Brooks said, the score has six of these “false endings” and continues for another 12 minutes because Beethoven, like many people, didn’t know how to stop. Brooks then played the grand finale, equipped with a cacophony of instruments and vocalists.

“Not bad,” he said. “My symphony may or may not look like that, but it can still be great, and so can yours. But I need you to remember four things: don’t rage against your change, teach others, take things away that aren’t the real you and surround yourself with love. … I truly hope you find the happiness you deserve.”

After the conclusion of his lecture, Institution President Michael E. Hill opened the Q-and-A by asking, “You’ve given us a prescription for the beginning, you’ve given us a prescription for the end, what

do you do in the middle?”

“Hold on,” Brooks joked. “Try to find Carlos a job. My talk next year will be on the middle.”