Lori Humphreys

Guest Writer

Reporter’s note: This week, Chautauquans will explore “The Forgotten: History and Memory in the 21st Century.” This theme offers the chance to remember three of an army of forgotten Chautauquans whose lives, like unseen rocks in a stream bed, shaped Chautauqua’s current yesterday and today. This week, a three-part series introduces or re-introduces three Chautauquans: Monday, artist Will Larymore Smedley; Wednesday, author and poet Rebecca Richmond; Friday, author, Chautauqua public relations czar and entrepreneur Julius King.

Residents and visitors may not immediately recognize their names, as neither street nor building exist in their honor. Born at the end of the 19th century, they lived most of their lives in the first half of the 20th century, that era of American energy and action. Their lives, talent and character suggest that they shared those national traits leavened by their unique, independent spirits. We remember them not because they were celebrated — we remember them because they seem to be models of lives well lived, an idea that Chautauqua embraces and encourages. Sometimes the glory of lives does not pass, it just hides until called in from the dark.

Will Larrymore Smedley

Listed

Who Was Who in American Art, 1999

Artists Blue Book North American Artists, 2005

Davenport Art Reference, 2005

Smithsonian Institution – Library of Artists

Artists in Ohio – 1787-1900 by Mary Sayre Haverstock

Memberships

Society of Artists and Illustrators, the Cleveland Society of Artists, Society of Independent Artists and the National Craftsman

Correspondence

Vassar College Archives, John Burroughs Collection; Yale University, Royal Cortissoz Collection; Mark Twain Archives, University of California

Exhibits

American Miniature Painters Society; The Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts; The American Watercolor Society; The Albright Gallery

If 21st-century readers and art aficionados do not recognize the name Will Larymore Smedley, they are not alone. His 20th-century neighbors might not have known him either. Smedley sought the shadows and lived unobtrusively with his wife, Adelaide Wilson, and daughter, Rose Thaline, at 11 Morris from 1908 until his death in 1957. If his repute jumped the fence, it was unremarked within the gates.

But it is within the gates, far from the nation’s art centers, that Smedley sought and succeeded to balance a life of utopian ideal and economic reality. His life emerges from the shadows in the memories of Chautauquan Mary Ellen Sheridan, the Daily digital archives, local Jamestown newspaper articles, archives at Vassar College and Cornell University, and Chautauqua’s Oliver Archives Center.

Smedley was a nationally acclaimed artist and illustrator when he moved to Chautauqua permanently in 1908. Yet his first mention in The Chautauquan Daily appeared in 1934. R. Jere Black, a popular mystery writer and neighbor, wrote, “ … I’ve never known a man who so hates praise, or even a just recognition of his genius.”

Robert Holder titled a 1959 article on Smedley as “The Story That Has Never Been Told.”

“It is hard to believe that in this century of the dramatic and in this age of advertising and publicity that a nationally-known master craftsman and artistic genius could have maintained his home so quietly for over 50 years so near to our busy Plaza,” Holder wrote.

With the exception of his 1951 interview, there is more Daily reporting about him after his death than during his lifetime. That may be due to the fact that his wife, Adelaide, lived to be 101 and her many birthdays are reported. There were four Chautauqua posthumous exhibits of Smedley’s work, the last in 2002.

Sheridan inherited the remnants of his work in 1988.

“He left the self-marketing and pursuit of grand venues as a low priority,” she said.

Now in her eighth decade, Sheridan knew Smedley since her childhood. He painted her portrait and sent her birthday cards with four-leaf clovers enclosed. She may be his last witness and her Aug. 11, 2002, Daily interview includes a vivid description:

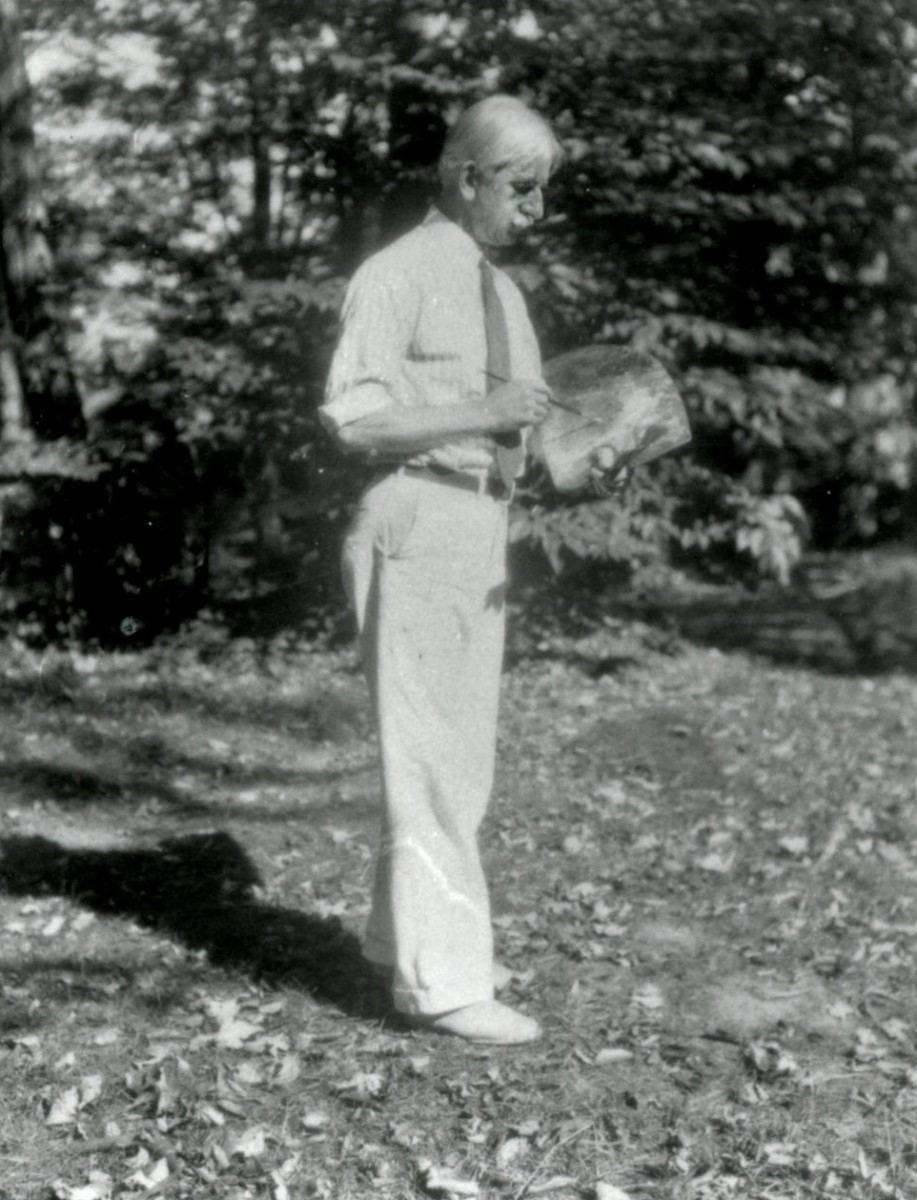

“He was tall, with long white hair, a bushy mustache, piercing brown eyes and beautiful hook nose. He always wore white in the summer and tennis shoes before anyone wore them. … He could be gruff and sarcastic. Many saw him as a recluse, but I never saw that side.”

Recently, Sheridan said that he was monumental in her growing up.

“Truth and beauty were the two tenets of his life,” she said. “Though he and Adelaide were poor as church mice, they were rich in their intellectual lives and relationship with one another.”

The only Daily interview with the man himself is dated July 6, 1951. Age may have mellowed his attitude toward publicity. Perhaps he saw the interview not as bragging, but a chance to share his ideas on art and reflect on the life he built.

“Art, specifically, must present the ‘illusion’ of reality — that is, it must imitate nature in order to focus man’s vision upon nature in a new and fresh manner,” Smedley told the Daily. “The artist must be constantly on the alert to experience and record fresh impressions if his art is to be worthwhile.”

He saw no conflict between art and science. He was, after all, an 1896 graduate of Case School of Applied Science, Cleveland, Ohio.

“While science attacks the problem of man’s existence from a technical standpoint, art attacks it from an intuitive standpoint,” he said. “ … I’ve lived the natural life and have found it very satisfactory.”

He commented about the technological changes which occurred in his lifetime, and was accepting of them.

“Each generation is separate from the next and thinks in its own way. But there are truths which span even the greatest of technical change,” Smedley said.

The interviewer, John Bailey, wrote that “Mr. Smedley believes that by staying close to nature, by basing his science and artistic interest upon something that is essentially unchanged and unchangeable, a man can get at what is most important in life.”

During the 1951 interview, Smedley said that Mark Twain had one of his paintings and the two corresponded. Two letters from Twain were featured in the 2002 Chautauqua exhibit of Smedley art.

If his personal life is arresting, his artistic life is also.

Smedley’s early career was marked by success and suggests he had confidence in his artistic talent. Though he graduated with a degree in engineering, he became an artist and a self- taught artist at that. askArt, a go-to site for artist biographies, states that he was “primarily self-taught.” This writer could find no mention anywhere that he took classes or studied with another artist.

He exhibited at the National Academy of Design in 1903 and 1904. He had a studio in New York and his work is mentioned in articles from 1904 in The New York Times and Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The July 6, 1951, Daily interview with Adelaide Smedley asserts that he drew 300 illustrations for the 1904 first edition of Encyclopedia of Horticulture, written by Liberty Hyde Bailey and published by Cornell University Press.

The Smedley family assertion presents something of an historical dilemma. There is no illustrator acknowledgement in the first issue of the Encyclopedia of Horticulture. A Cornell University archivist did not find any reference to Smedley in Bailey’s archives without intensive research in Bailey’s papers. This does not mean that it is not true, only that the science of history and the history itself are not always in sync.

“I’m annoyed with Bailey that nowhere did he give Will credit. My father-in-law, Laurence Vintage Sheridan, a landscape architect, went through the first edition and only found one picture with Will’s initials,” said Sheridan.

The arc of his professional life changed in 1906 when he was hired as a faculty member of the Los Angeles School of Art and Design. According to Black’s Daily 1934 comments, he “became home-sick, and after one day shook the job and shot back to his beloved Chautauqua.” If there were other reasons, they are unknown.

Though Chautauqua was a refuge where Smedley and his wife could live the simple life they envisioned, he had to heed economic reality. Art was his life and living, and he faced that fact honestly and bluntly. Smedley wrote in a 1912 Fine Arts Journal article, “without sales of their wares neither artist, nor baker nor candlestick maker can do their best.” He was not above soliciting consideration of his skill and offered his services to nature writer John Burroughs in a 1918 letter.

Ironically, it’s the intersection of art and commerce which reveals much of Smedley’s artistic career after his move to Chautauqua County. He had studios at the Colonnade, Room 18. and the old Arcade, and advertised “Smedley Painting Class” in a 1917 issue of The International Studio. The Jamestown art community recognized his quality and in 1910 hired him to teach at the Jamestown Brush and Pencil Club. In 1916, the club exhibited 35 of his oil and watercolors. The Jamestown Evening Journal reported that three to four hundred people viewed the show.

This writer could not find information about his paintings after 1937. Julius King acknowledged him as science consultant for King’s 1934 publication Talking Leaves and 1936 publication of Wild Flowers at a Glance. Sheridan said that Smedley continued to do magazine illustrations, private commissions and magazine articles.

On July 13 at the Patterson Library, Westfield, Sheridan auctioned the Will Larymore Smedley paintings and drawings she had lovingly guarded since 1988. Among the paintings was “Forest Idyll,” the 1903 National Academy painting which the Smedleys had kept all their lives.

“I was relieved,” she said. “It was a lot of responsibility protecting his paintings and reputation.”

After spending time with Smedley in the archives and listening to Sheridan’s memories, there was something bittersweet about watching Smedley’s paintings leave her care, akin to watching a friend’s possessions in stranger’s arms. Smedley would return to the shadows, his art hanging on unknown walls.

But history is capricious and may have another plan. Sheridan reported that Julia Klevin plans to hang the paintings she purchased at the auction on the walls of her future Westfield business.