The Silkroad Ensemble embraces difference.

Ten of its members brought that philosophy to the Amphitheater stage Monday, Aug. 6, as a twist on the traditional 10:45 a.m. morning lecture, opening Week Seven’s theme, “The Arts and Global Understanding.”

Following the morning announcements, the Amp filled with the nasal sounds of Galician bagpipes, accompanied by percussionists Joseph Gramley, playing a rattle, and Shane Shanahan, playing a melody on a conch, as they ambled through the aisles. As they reached the stage, a cacophony of strings and percussion instruments erupted.

The piece, John Zorn’s “Book of Angels,” featured folksy Jewish harmonies equipped with undertones of lute-like instruments and drums. As the piece ended, Galician bagpiper Cristina Pato stepped forward to address the packed audience.

“Twenty years ago, curiosity brought Yo-Yo Ma to gather musicians from all around the world, … the curiosity about learning about other cultures, the curiosity about learning about other instruments,” Pato said. “And he had one very simple question in mind: What happens when new social groups meet?”

The famed cellist Ma established Silkroad in 1998 as a way to engage differences through music, and as a metaphor for the benefits of a globalized, connected world through musical innovation. Evidence of this is in its members, who Pato turned to introduce.

Wu Man, a pipa virtuoso and original Silkroad member, plays her traditional Chinese instrument around the world in contemporary and classical settings while bringing age and experience to the ensemble; Mike Block, a cellist, brings innovation through his rigged cello, which allows him to play his instrument — which traditionally requires the musician to be seated — while standing.

Education is another pillar of Silkroad Ensemble, Pato said. Pato herself is a teacher; percussionist Gramley is a professor at the University of Michigan and Martine Thomas is a Harvard University alumna who participated in Harvard’s collaboration with Silkroad Ensemble as part of “The Silk Road Project.”

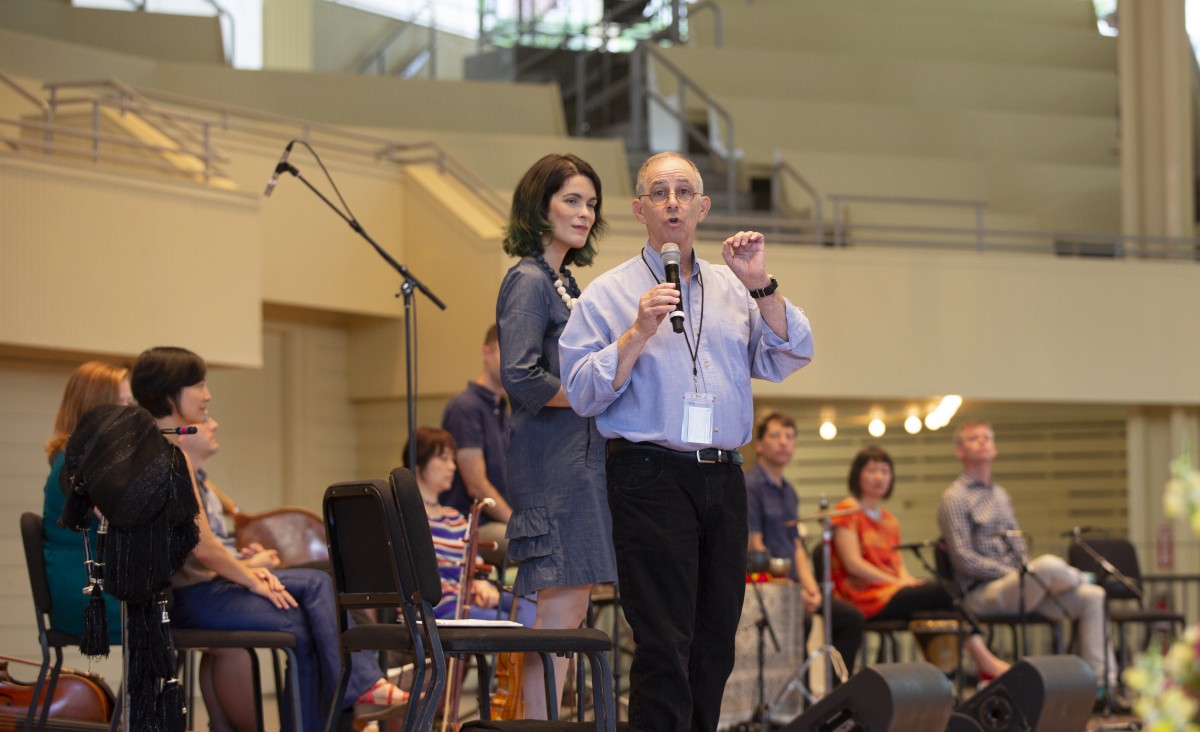

The lecture was led by Steve Seidel, director of the Arts in Education Program at Harvard Graduate School of Education, who frequently works with the group. When he met Silkroad 10 years ago, he was struck by its members’ dedication to learning — both about themselves and those around them. Seidel introduced the theme for the morning: listening as art.

Listening is best expressed during rehearsal, he said.

“You go into rehearsal with your instrument or, if you’re working as an actor, with your text, and fully expect to make sound, to make noise, to express,” Seidel said. “But from a learning perspective, a rehearsal does not have to be a learning environment — and without listening, it rarely is. Listening is the turning point … that takes the making of noise into the making of meaningful sound.”

Seidel called on percussionist Shanahan and violinist and erhu player Shaw Pong Liu to discuss the rehearsal process for “Book of Angels,” which Liu previously only performed twice compared with Shanahan’s 50 times. Shanahan described the necessity to understand body language as a form of listening, both on and off stage.

For Japanese percussionist Haruka Fujii, her culture inspires her music. “Ma,” — yes, like Yo-Yo Ma, she said — is the Japanese concept of negative space. “Ma,” in the physical sense, can be the distance between two people; it can be the emotional distance; or in the musical sense, it can be “the space between sound and sound,” a concept Japanese composer Tōru Takemitsu explored in his piece “Seasons.”

Fujii looked to replicate this concept at Chautauqua Institution. The musicians scattered; some took their instruments to the top of the bowl, others went empty-handed to various points along the stairs, ramps and throughout the orchestra pit. After the clang of the gong, the musicians began improvising noises. After a few minutes, Seidel gestured for the audience to join.

Eventually, the Amp over-flowed with noises, rattles and claps. Attendees whistled, rolled and sloshed water bottles, rustled clothing and paper, clinked jewelry against seats, stomped and drummed rhythms into railings. The clamour began to resemble a jungle or noisy summer evening, coincidently equipped with a metronome of a truck’s back-up beeper.

After a few more moments, Seidel gestured a decrescendo. He paused, and asked the audience to pause as well, because “silence is a space in which we can collect our thoughts.” Then he asked the audience to discuss with those around them.

The Amp burst into chatter.

“While you were talking, I was listening, and that was a fantastic sound,” Seidel said.

Seidel turned back to the concept of listening, a topic percussionist Sandeep Das knows well. Das lived with Guru Pandit Kishan Maharaj for 12 years, studying the traditional Indian instrument, the tabla. During this time, Das learned to practice space, similar to the Japanese concept of “ma,” and listening — listening to his instrument.

Das and Shanahan played together to demonstrate the relationship between sounds and musicians. Das began with slower rhythms on the tabla, which Shanahan accented with strikes to a singing bowl. The rhythms progressively increased in intricacy and speed. By the end, the two men’s melodies meshed seamlessly as they finished in sync.

Pato closed this portion of the lecture, explaining Silkroad and Ma’s core principle.

“In ecology, the point in which two ecosystems meet, such as the forest and the savanna, that point is called the edge effect, and apparently in that point is where more new life forms are created. And somehow Silkroad is (Ma’s) own recreation of the edge effect.”

-Cristina Pato, Galician bagpiper, Silkroad Ensemble

Institution President Michael E. Hill opened the Q-and-A by asking what lessons can be drawn from listening and incorporated into discourse.

“There’s often the experience when you can’t hear someone — whether that’s based on how loud they are speaking or you can’t understand or agree with what they are saying — (and) you might feel a sense of frustration or fear,” said Jeffrey Beecher, bassist and co-artistic director of Silkroad. “… I think what this experience has taught us … is rather than shout … I trust that by actually going somewhat quieter, by lowering my energy in some way, (is effective) instead of trying to forcefully get something across.”

Hill then turned to the audience for questions; an attendee asked if silence had its own sound.

“Silence is the moment of interaction,” Block said.

With that, the ensemble closed the lecture with a song. The piece featured a snakey beat, enhanced by the erhu, a two-stringed predecessor to the violin, played by Liu, a strong beat and intense bowing from the strings section. The audience clapped along as the ensemble finished con gusto.