Review by Howard Halle-

Depending on whom you ask, sometime within the next 20 to 50 years, the United States will become a minority/majority nation. That’s basically an oxymoronic way of saying that people of color will make up the largest piece of the population pie, a prospect unsettling to the considerable segment of white Americans who voted for a president more than happy to shred the Constitution to hold back the tide.

Nonetheless, demographic change is coming, and its stubborn statistical inevitability will utterly transform American life forever. Indeed, within the realm of contemporary art, one could argue that it already has.

As proof, look no further than the Fowler-Kellogg Art Center’s current offering, “Reconstructing Identities,” curated by Erika Diamond and closing Tuesday, which presents the work of five contemporary artists of color: Sonya Clark, April D. Felipe, Roberto Lugo, Jiha Moon and Wendy Red Star. The main question it poses, “Who gets to be represented in art?” is one that has been kicking around the art world for more than 20 years. In 1993, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted what became the most controversial edition of its signature showcase: the Biennial. It was the first major institutional exhibition — anywhere — to tackle the rise of multiculturalism and its attendant storm of identity politics. The show included a 10-minute videotape of the Rodney King beating by artist George Holliday, while another artist, Daniel J. Martinez, designed an admission button that read: “I CAN’T IMAGINE EVER WANTING TO BE WHITE.” Needless to say, the reaction by the largely white, male critical establishment was resoundingly negative, with one — Michael Kimmelman of The New York Times — stating flatly, “I hate this show.”

There’s nothing quite as confrontational here as Martinez’s piece, though the debate it sparked still informs “Reconstructing Identities.” The show deals with, yes, identity, but also with how the Europeanized arc of history and culture might be bent to reflect an ever-diversifying society.

Case in point: a series of digital color photographs by Red Star. In them, Red Star, a Native American born in Billings, Montana, and raised on the Crow Reservation, debunks the romanticized view of Native Americans, using a play on the classical four seasons theme to expose the emptiness of Old West mythology. She poses within sets representing winter, spring, summer and fall, wearing native attire appropriate to the time of the year. Each backdrop is evidently fake, as are certain props like the inflatable plastic deer next to Red Star in her depiction of autumn. However, she subverts the artifice of each scene with her own resplendent presence, which is incontrovertibly real. Thus, she reclaims a cultural space for both herself and her heritage.

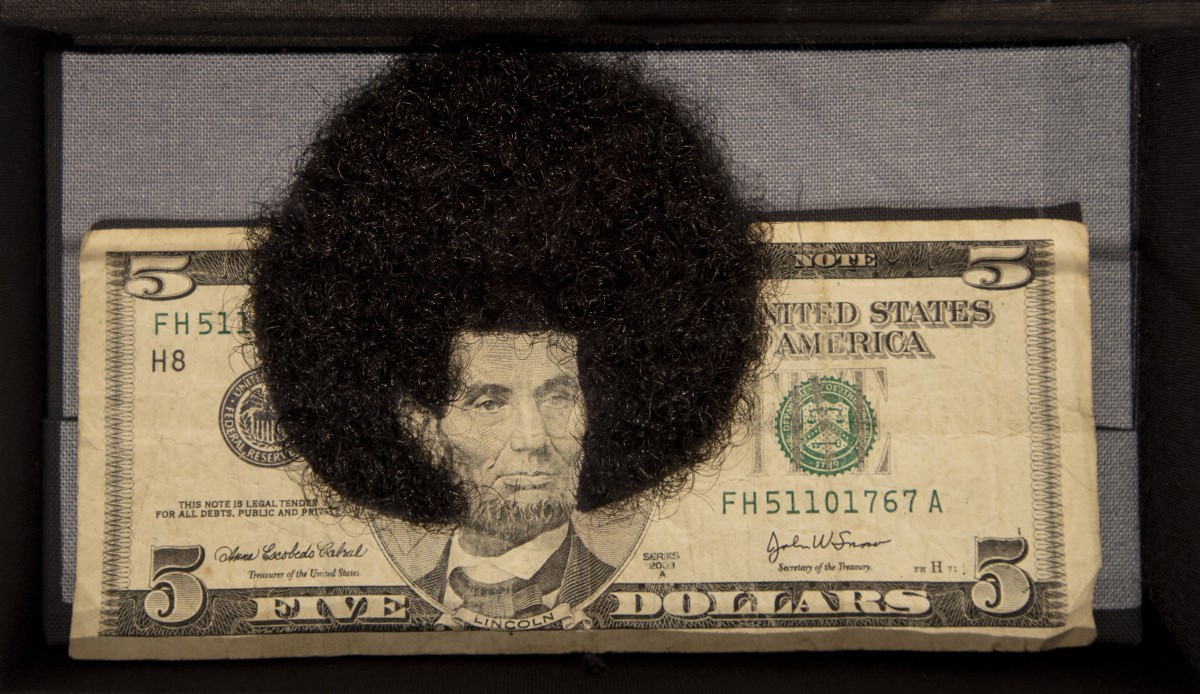

African American artist Clark deals with intractable issues surrounding race by delving into American history. Clark, a professor of art at Amherst College who is of Afro-Caribbean descent, explores the Civil War and how it continues to resonate today with a number of works, like a pair of small cases with a $5 bill laid inside each. One has the head of Abraham Lincoln, the “Great Emancipator,” wreathed in a huge Afro made of black fluff glued to the note. The other is entirely encrusted in translucent crystals that encase Lincoln’s image as if it were buried in ice, suggesting, perhaps, the broken promises and glacial pace of racial justice over the 150 years since slavery ended. Elsewhere, Clark presents a shelf with three small piles of yarn on it: one red, one white, one blue. They are the unraveled remains of the Stars and Bars, the former Confederate battle flag, which is now an icon of white supremacy. Here, Clark notes the irony of how this banner of hate shares the same color scheme as its emblematic opposite, Old Glory.

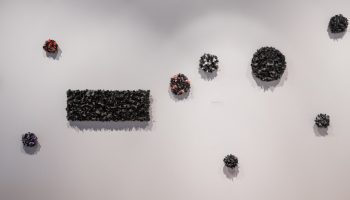

For Lugo, a Philadelphia native born to Puerto Rican parents, the issue of identity is bound up in his roles as potter, painter, musician and social activist. Having never received a formal art education, he is essentially self-taught, yet his bowls, plates, vases and figurines possess the ornate craftsmanship of the finest products that came out of the workshops of Ming-dynasty China or 18th-century France. His ceramics incorporate references to hip-hop and are often decorated with portraits of important personages from history and pop culture such as Frederick Douglass and rap artist, The Notorious B.I.G. In several wall-mounted medallions, Lugo evokes Luca della Robbia, the Florentine Renaissance master known for his vividly polychrome, tin-glazed terracotta statues and reliefs, with one object depicting the profile of Martin Luther King Jr., as if he were a Medici prince.

Born in Korea, Moon lives and works in Atlanta, and describes herself as a “cartographer of culture” who draws upon Eastern and Western art, as well as folk tradition, advertising and corporate design. This varied jumble of sources yields compositions that resemble phantasmagoric bouquets of symbols, including one large example recalling a kite or fan. It contains a painterly thicket of overlapping landscape and floral motifs interrupted here and there by smiley faces and Pennsylvania Dutch hex signs.

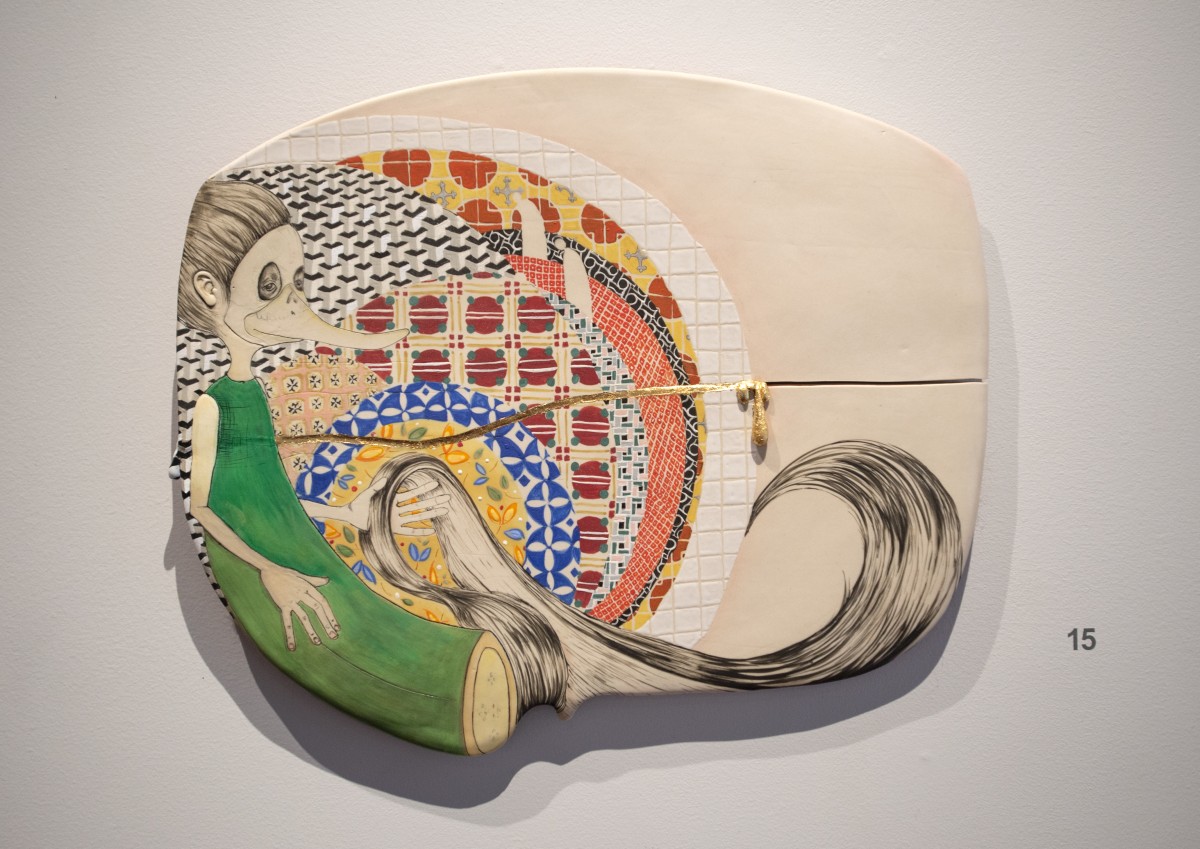

While these artists more or less tie their notion of identity specifically to race or ethnicity, another ceramicist, Felipe, ponders the more personal question, “Where do I belong?” Born in Queens to parents from the Caribbean, Felipe cites her mixed ancestry as the reason for never feeling like she belonged to any particular group, while still being regarded as a person of color. As a metaphor for the vicissitudes of finding a way to fit in, Felipe turns to the childhood tale of “The Ugly Duckling.” The story finishes with the titular character turning into a swan, but Felipe prefers a more inconclusive narrative frozen at the tipping point between duckling and swan, ugliness and beauty, social rejection and social acceptance. In one relief sculpture, Felipe imagines this developmental-limbo as a circular space shoved to one side of an expansive, irregularly shaped plaque. It’s filled with a cacophony of clashing tile patterns and occupied by a recumbent woman — possibly the artist herself — wearing a mask in the shape of a duck with a long bill. Her head and arms are plunked onto a curving green form that appears to be a plantain with the far end lopped off. She holds a long fall of hair, which seems to originate from the back of her head, though it’s hard to tell because the latter is cropped out of the picture.

The puzzling nature of this figure speaks to the larger enigma of identity and the contingent circumstances of its formation. We are all born with an identity that is at once innate and shaped by outside forces such as family, ancestry or community. Each of us is a unique being, attached by varying degree to one cohort or the other. The extent to which someone privileges the former over the latter really depends on psychology and a sense of self-worth. But it is also one of the realities of human nature that in times of duress or perceived threat, we cling more tightly to tribe — a situation that, as history teaches us, can be extremely destructive. We are living in such a moment, as the battle over who gets to be represented is being joined. “Reconstructing Identities” points to one hopeful outcome — over another that is far more dangerous.

Howard Halle is editor-at-large and chief art critic for Time Out New York.