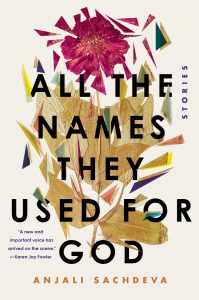

After finishing the last story of the collection that would become the critically lauded, Chautauqua Prize-winning All the Names They Used for God, Anjali Sachdeva went back to the beginning. At that point, her debut was still without a title, and her agent suggested she write an introduction as a way to delineate the whimsical, genre-bending stories inside the manuscript for potential publishers — and for Sachdeva herself.

After finishing the last story of the collection that would become the critically lauded, Chautauqua Prize-winning All the Names They Used for God, Anjali Sachdeva went back to the beginning. At that point, her debut was still without a title, and her agent suggested she write an introduction as a way to delineate the whimsical, genre-bending stories inside the manuscript for potential publishers — and for Sachdeva herself.

“I can say I did not go into this with a plan,” Sachdeva said.

In writing the three-paragraph opening that appears in the paperback edition of All the Names They Used for God, Sachdeva found that a broader idea of characters “searching for or struggling with a force bigger than themselves” linked the nine stories. From this perspective, “All the Names They Used for God” — the title at the centerpiece of the collection — applied to the work as a whole.

The $7,500 annual Chautauqua Prize celebrates a book that provides a richly rewarding reading experience and honors the author for a significant contribution to the literary arts. That author, Sachdeva, will offer a reading from that book, All the Names They Used for God — selected from 205 nominated books — at 3:30 p.m. Friday, August 16 in the Hall of Philosophy. A book signing will follow.

After settling on a title, Sachdeva’s publisher was “understandably concerned” that readers would misconstrue the work as a religious text. The author looks to the book’s epigraph, a Ralph Waldo Emerson quote from his essay, “Nature,” to encapsulate her intentions.

“There is definitely a theme of faith, but I think it aligns more with that transcendentalist idea of the sublime role of nature,” she said. “There are a couple of stories where faith in God and religion is a central focus, but there are other stories where it is about a faith in nature, or a faith in art or magic.”

These stories “walk the knife-edge between” wonder and terror, as Sachdeva writes in her introduction — encompassing everything from a translucent mermaid to the Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping in Nigeria.

For Atom Atkinson, director of literary arts, the Prize presentation is an opportunity for Chautauquans to directly enjoy the benefits of the Prize readers’ work.

“Among the things we ask readers to keep in mind when they’re recommending books to advance to the next level of judgment is whether this is the kind of book they could imagine a lot of different kinds of readers picking up, finishing and then talking about,” they said. “That’s how literature has thrived at Chautauqua for a long time. Our Prize reflects that. We’re really excited to have, once again, a book that fits that bill.”

The eighth pick in the history of The Chautauqua Prize, All the Names They Used for God is the second short story collection to win, the first being Phil Klay’s National Book Award-Winning Redeployment in 2015.

“Collections are a really rich zone of intellectual inquiry,” Atkinson said. “You’re able to think about each (story), its own implicit thesis about how the world works and what it has to offer you as the reader and its characters, and then move on to the next set of rules and set of values, and think about how all of those live alongside each other and inside you. You do all of that work even before you get to talk to someone else about it. It’s a really rich, dynamic foundation for a community discussion of literature.”

On Tuesday, Chautauquans dined in the Athenaeum Hotel Parlor during the 2019 Chautauqua Prize dinner, an evening originally conceived by Sherra Babcock, former vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, and her team in order to celebrate both the winning author and the nearly 80 Chautauquans who serve as readers for the prize. The physical prize, which was revealed at the dinner, is a sculpture created by Kirsten Engstrom. Evocative of Sachdeva’s grimly humorous short story “Manus,” the Prize features two hands — one human and one alien — resting on top of each other.

“The Chautauqua Prize dinner was first conceived as a way to reflect the fact that this is a very distinctly community-oriented prize,” Atkinson said. “It honors the readers in spirit because it’s saying we need to have a special gathering to reflect that fact that we couldn’t do this without our community. What does it mean to pick a book to celebrate together?”

Matt Ewalt, current vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, said he was “excited to celebrate Anjali and her remarkable debut work, work that cuts across genre and breaks down our traditional reading silos.”

Both Ewalt and Atkinson agreed that the diverse subjects in All The Names They Used for God have enabled more connections across a broad community of readers.

“(All the Names They Used for God) could be described as magical realism in a lot of places, but it is preoccupied with the things that all literature is preoccupied with — things like destiny, the meaning of life, how that reflects on the answer for all of humanity,” Atkinson said. “These stories are tethered to questions around capital ‘G’ God and the broadly spiritual questions that lie just beneath the surface of all of our everyday interactions and crises. I can’t wait for everyone to read it.”

Citing collections like Clare Beams’ We Show What We Have Learned and Brian Evenson’s Song for the Unraveling of the World — as well as the work of short story authors Kelly Link and Kevin Brockmeier — Sachdeva said the ideas inside her own collection are “not enough (on which) to write 200 to 300 pages.”

“(The short story) has the ability to consider one really specific idea and its human implications,” Sachdeva said. “A lot of people have said to me that they’re surprised by the variety of stories in (All the Names They Used for God). That’s partly because I wrote (the collection) over a long period of time. But it’s also because that’s what is enjoyable to me about writing short stories. I can write about an isolated pioneer woman and then switch to a totally different mode and write a story set in the near future.”

All the Names They Used for God opens with “The World By Night,” a story set in the 1800s about a woman — the aforementioned “isolated pioneer woman” — who investigates an intricate cave system inspired by Sachdeva’s own tour of Kentucky’s Mammoth Cave National Park. Sachdeva recalled how, during her hour in the cave, the park guide explained how individuals once explored the dark passageways with only candle lanterns. Even now, with technology advanced far beyond wax and fire, spelunkers have to be cautious in the face of nature’s maw.

“They still get lost,” Sachdeva said.