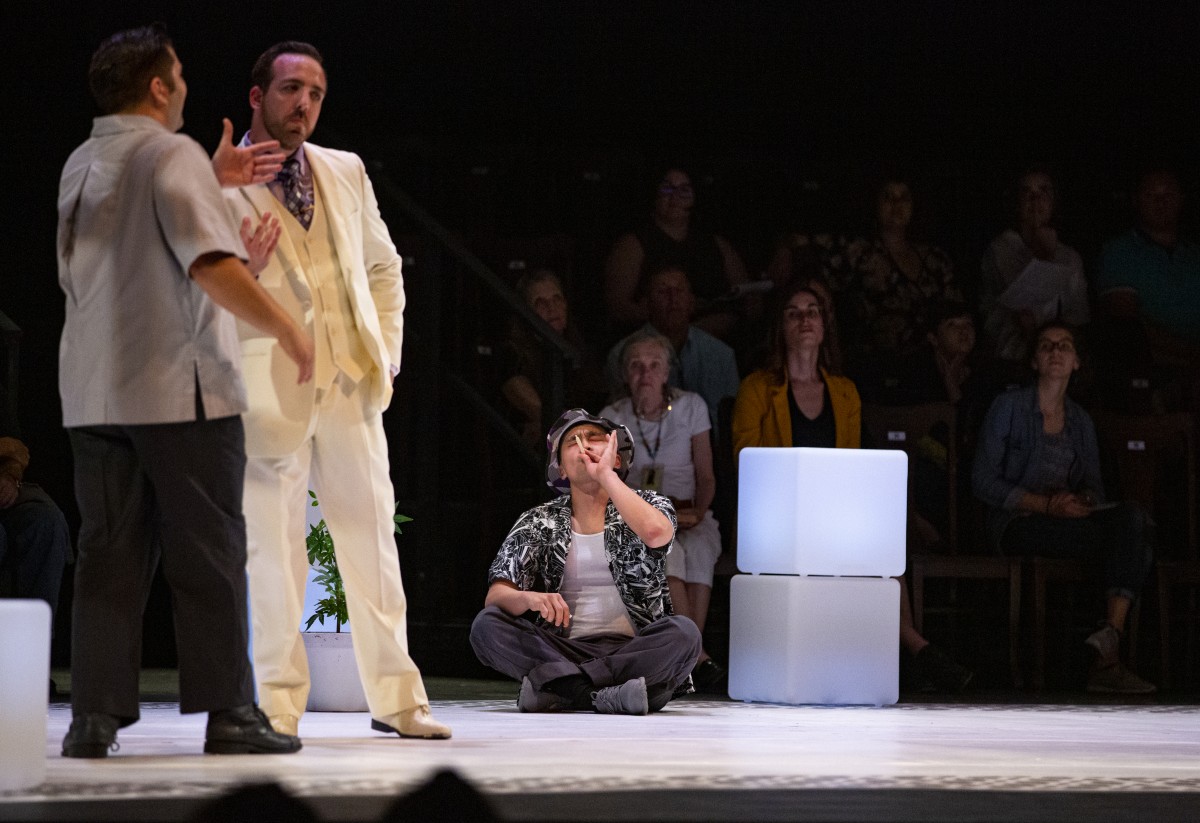

Tom Di Nardo, for the daily

To experience The Ghosts of Versailles, following the other two operas which make up the famous Beaumarchais trilogy, has been a rare opportunity, a challenge and triumph for Chautauquan vision. Few organizations have the resources, or the desire, to present them all — in diverse staged interpretations — on three successive nights.

Ghosts was written to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Metropolitan Opera in 1992. For composer John Corigliano and librettist William M. Hoffman, it meant creating an opulent, extravagant hybrid, continuing the principle of adaptation which has followed the trilogy for over 237 years.

Beaumarchais, whose family was forced to convert to Catholicism and who had a bitter distrust of authority, wrote his Barber of Seville in 1774, with many revisions shifting the original boos to cheers. In 1782, it was adapted into an opera — not the famous opera by Rossini, but the then-much more famous, though serious, one by Giovanni Paisiello. The story of the crafty barber Figaro helping a Count to woo his lady soon became the most-performed opera in Italy and, after over 60 performances just in Vienna, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and librettist Lorenzo da Ponte were looking for an opera subject to mirror Paisello’s success.

Books have been written about the scandal involving Beaumarchais’ 1781 central work of the trilogy, The Marriage of Figaro, and Louis XIV’s later-relaxed pronouncement: “This is atrocious, it will never be played.” First off, its theme was a blatant challenge of the droit de seigneur, the right of an aristocrat to deflower any woman in his employ. Besides that, the idea that a lowly barber and his fiancé could team up with a Countess to foil the Count’s amorous adventures with the bride was another outrageous provocation of disrespect toward royalty’s power. Da Ponte somehow fooled Roman Emperor Joseph II by claiming the story was just a harmless comedy, but the principles of social freedom spread across Europe faster than even Beaumarchais could have imagined.

Because of the medieval principle of the droit de seigneur, it’s difficult to update the work out of the period, yet the idea of an undocumented immigrant’s complete dependence on the whims of a conniving employer was a canny angle to make the present staging relevant.

Mozart wrote this work of genius in an astonishing six weeks in 1784, intending to adapt Figaro into a successor to Paisello, but with musical clues the Viennese audiences would understand. In both operas, for instance, the Countess enters after much has happened, singing plaintive love music supported by two clarinets, and in the same key — E-Flat. At the premiere, some reports claim that some artists conspired to sing poorly but, by the third performance, so many encores of whole numbers were necessary that Emperor Joseph made an edict that no repeats for more than one voice would be allowed.

This writer is not alone in believing that this masterpiece, in its musical genius, magnificent libretto, dramatic as well as comedic sequences, and importance as a social earthquake, represents one of the pinnacles of Western art.

Fast forward to 1816, when Gioachino Rossini dared to write his own, more comic version of the first play, The Barber of Seville, though Paisiello’s was still being performed more than any other opera in Europe. This is equivalent to someone today writing another version of Hamilton or The Lion King, a gutsy enterprise with Paisiello’s fans turning the premiere into a fiasco — though who’s heard of Paisiello now?

We finally reach the third play of Beaumarchais’ trilogy, The Guilty Mother, the last play he wrote. The Countess has had a son, Léon, by the young troublemaker Cherubino, and the Count a daughter, Florestine, by another woman — but, in this male-dominated world, the Count cannot forgive his wife despite his own indiscretions and forbids the two youngsters to marry. In Beaumarchais’ play, the evil Bégearss (a name based on a crooked lawyer who slandered the playwright) tries to steal the inheritance of Léon and marry Florestine, but Figaro and Susanna foil the plot and everything ends happily.

Approaching this final play, Hoffman took the spirit of adaptation to a higher level. He placed the setting in the halls of Versailles, where Marie Antoinette, Louis XVI and many specters of the past are haunting the walls, and about to watch Beaumarchais put on his final play.

But, in the second act, the characters combine; Beaumarchais falls in love with Marie Antoinette, and hopes to rewrite his characters so that history is changed, the French Revolution is averted and she is saved from the guillotine. A valuable necklace is essential to buy passage to America, but Figaro dislikes Marie and refuses to play by the script — even though Figaro is simply one of Beaumarchais’ fictional characters. Eventually Bégearss is foiled, Marie accepts her fate, and the original Guilty Mother has been transformed by inspired theatrical imagination.

There were plenty of chances for Hoffman to have fun with this unusual mixture of already-defined personalities, with ghosts eventually just as real and dramatic as real characters. Corigliano must have had fun writing star turns for an Egyptian singer (a flamboyant romp by Marilyn Horne in 1992), Bégearss’ tribute to the indestructible worm, and long solos by Marie Antoinette.

Beaumarchais would probably have been thrilled to think that his social denouncements had passed through the transformations of so many talented and revered artists, while the royalty his works threatened are long forgotten. He might say, Vive l’adaptation!

Tom Di Nardo is a Philadelphia writer on the arts. His recent books include Listening to Musicians: 40 Years of the Philadelphia Orchestra and Performers Tell Their Stories: 40 Years Inside the Arts. He has also written Wonderful World of Percussion: My Life Behind Bars, a biography of legendary Hollywood percussionist Emil Richards.