Review by Vicky A. Clark-

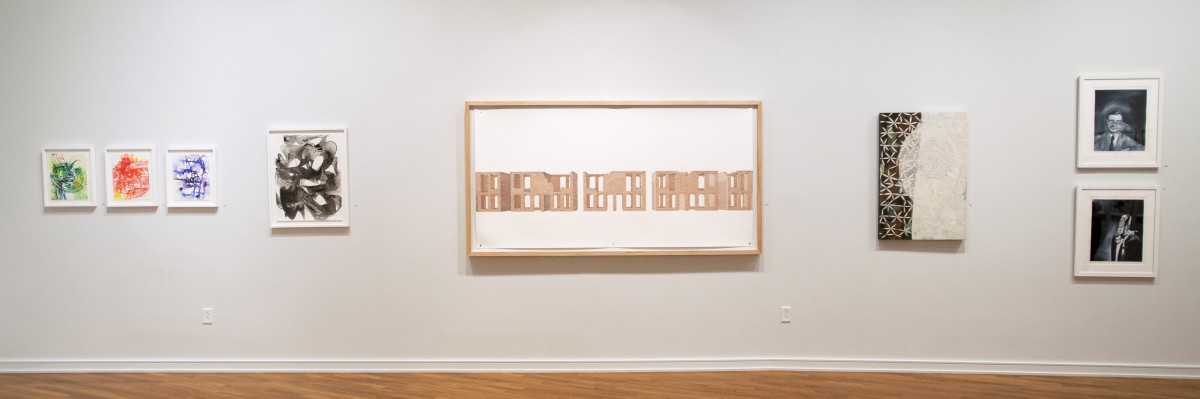

“On Common Ground: Works on Paper” at the Strohl Art Center, curated by the Susan and John Turben Director of VACI Galleries Judy Barie, shows how the medium of drawing has changed.

Traditionally, drawings were used as preliminary sketches for more formal works, but some artists had such a deft hand and rendered the smallest details so perfectly that a drawing looked like a finished work. Someone like Albrecht Dürer could capture the most detailed world in his prints, utilizing hidden symbols to add meaning to his mostly religious subjects. Leonardo da Vinci, in contrast, filled notebooks with ideas for inventions, drawings of human anatomy, and quick studies of nature. Centuries later, artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres continued to produce highly detailed portraits, but some, like Henri Matisse, experimented with new methods, landing on his famous paper cutouts when his physical situation deteriorated so much that he couldn’t continue to paint. The definition of drawing continues to expand with artists using new methods and techniques such as fiber or videotape. Tree branches can be used as a drawing tool or as components of the composition. From preliminary study to scientific rendering to abstract composition, works on paper have captivated viewers for centuries.

While many historic drawings were never meant to be framed and shown in a museum, things have shifted substantially in the modern era with some artists only producing drawings. Additionally, artists have increased the size of their work and have been experimenting with new materials. Sometimes the final product is a cross between drawing and photography, painting, sculpture, and even film.

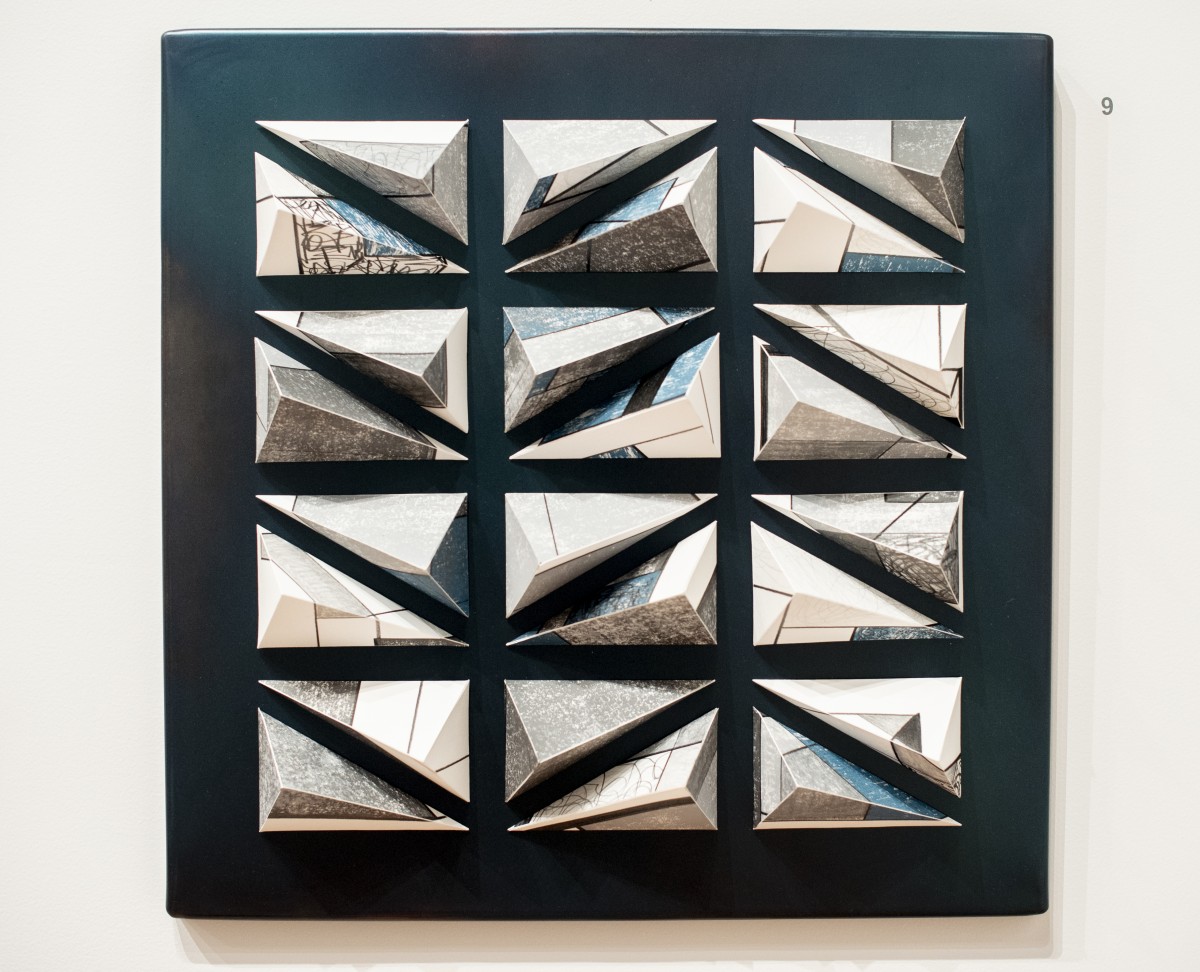

Brenda Stumpf makes mixed-media works by adding a variety of materials to her surface, creating, ironically, a texture that resembles layers found at excavation or archaeological sites. Her most recent work has been influenced by her new house, an old church that she is restoring. In “Revelation” and “Invocation,” steel beams replace paper as a surface, adding to the architectural and structural grounding. Stumpf then produces a light-filled, scumbled ground that evokes the mystical and the sacred, in both places and people, with traces of histories, stories and states of being in her combination of real and imagined worlds. Her work could be considered maps that have moved far beyond geography. Her aesthetic and conceptual combinations can also be seen in her sculpture, including “To the Unknown” that is included in the “Small Sculptures: Big Impact” show.

A similar interest in enriching the surface, adding texture and depth, is a characteristic of the work by Bridget Quirk. She, however, uses kitschy materials, most notably fake hair, to animate her colorful portraits. Collage became popular in the early 20th century, as artists began to flatten their picture plane, fracturing objects into intersecting planes to create spatial confusion. Soon, that deconstruction included content as well, with an accumulation of symbols or disparate items that create a personal iconography. Using such a variety of materials — pastel, acrylic, hair, colored pencil and magazine cutouts — Quirk enhances the spatial inconsistencies as her cast of characters seem slightly out of sorts, broken down into parts and then pieced back together. The eyes, clipped from magazines, add a disconcerting touch of realism, and we are left with more questions than answers about her subjects’ identities. Although based on photographs of important people in her life, they seem like sketches for idiosyncratic players in the theater of the absurd, anime or video games, or perhaps people featured in Saturday morning cartoons.

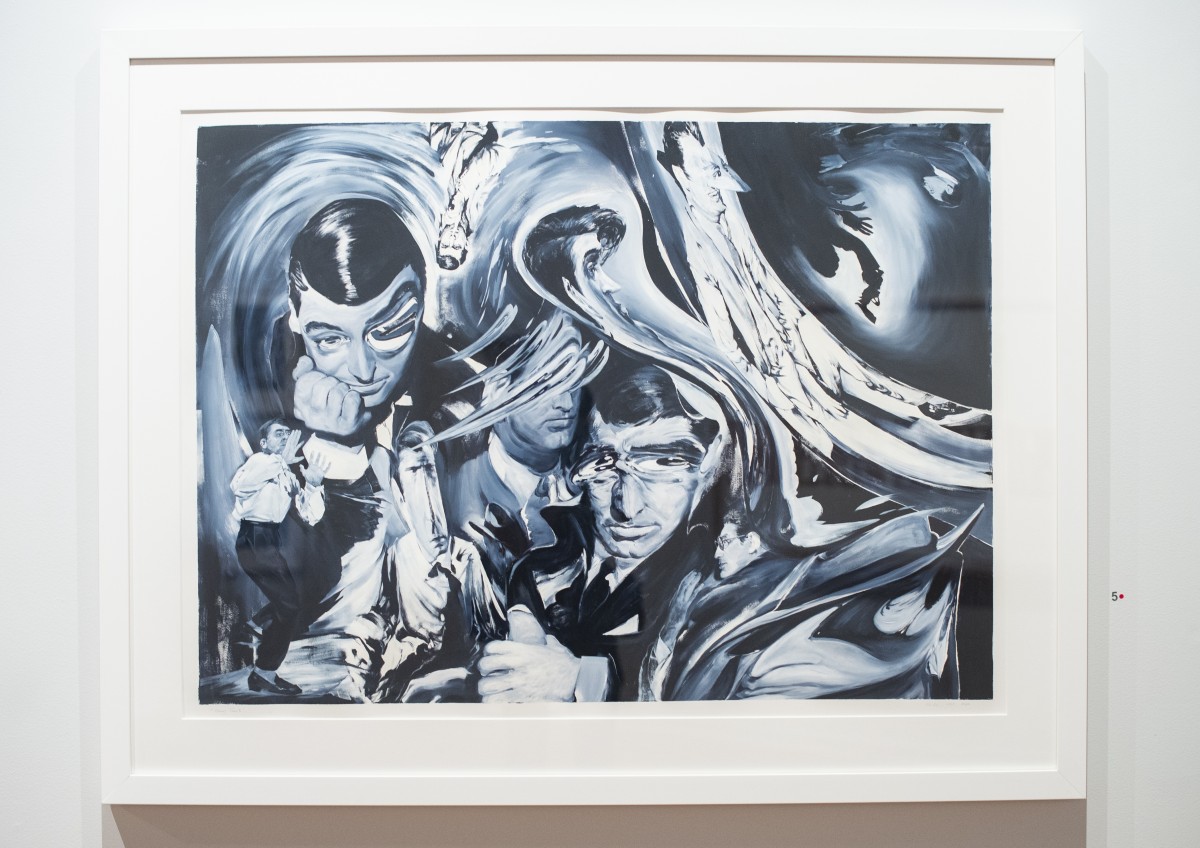

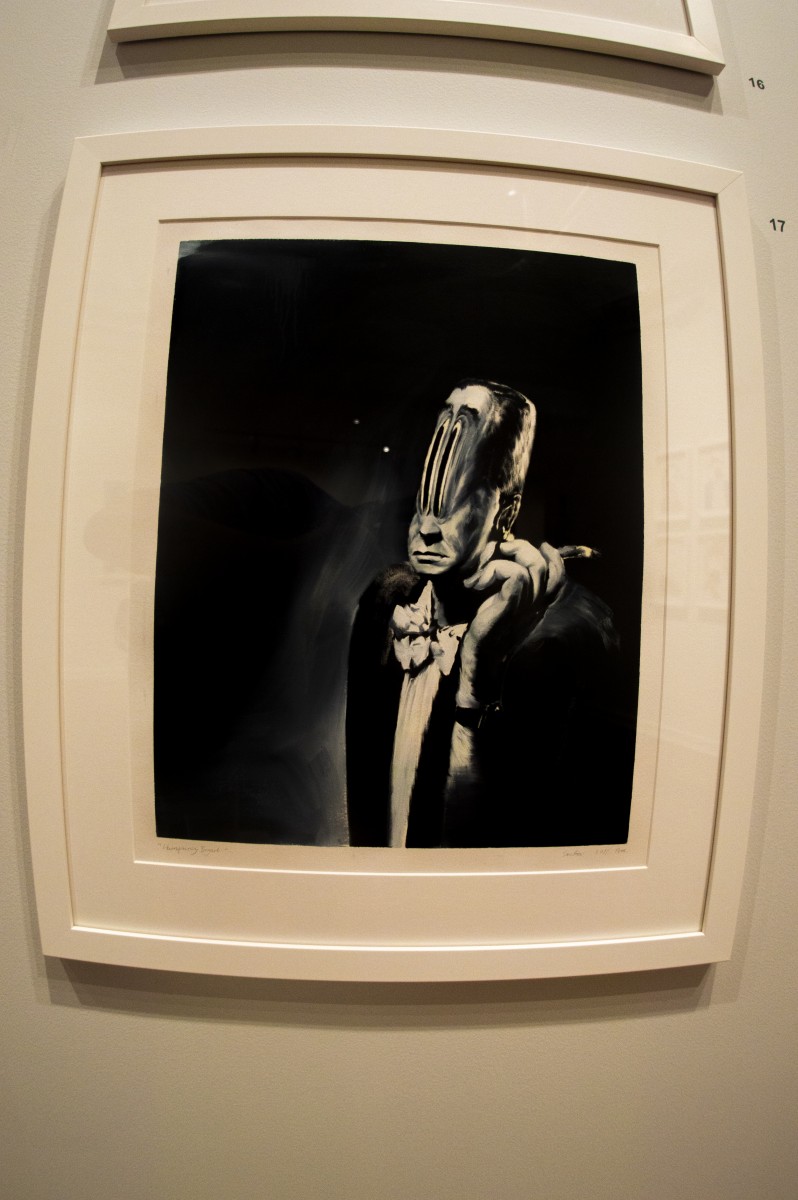

An artist whose work relates well to Quirk’s is Su Su, who emigrated from Beijing to Pittsburgh, in 2011. Like many transplants, she views the world through a bifurcated lens, and she channels her interests in intersections, juxtapositions and disconnects into her paintings where she experiments with complex, often disjointed, compositions as well as new painting materials. For this show, she contributed three paintings on paper of pop culture icons, Cary Grant, Mr. Rogers and Humphrey Bogart. Restricting her palette to an eerie bluish/gray-like sepia, stretching and distorting her faces like visual effects artists or English artist Francis Bacon, she presents a radically different interpretation of these men. They have been put through a blender and then placed in front of a funhouse mirror, perhaps to star in an episode of “The Twilight Zone” or some sci-fi, shape-shifting adventure.

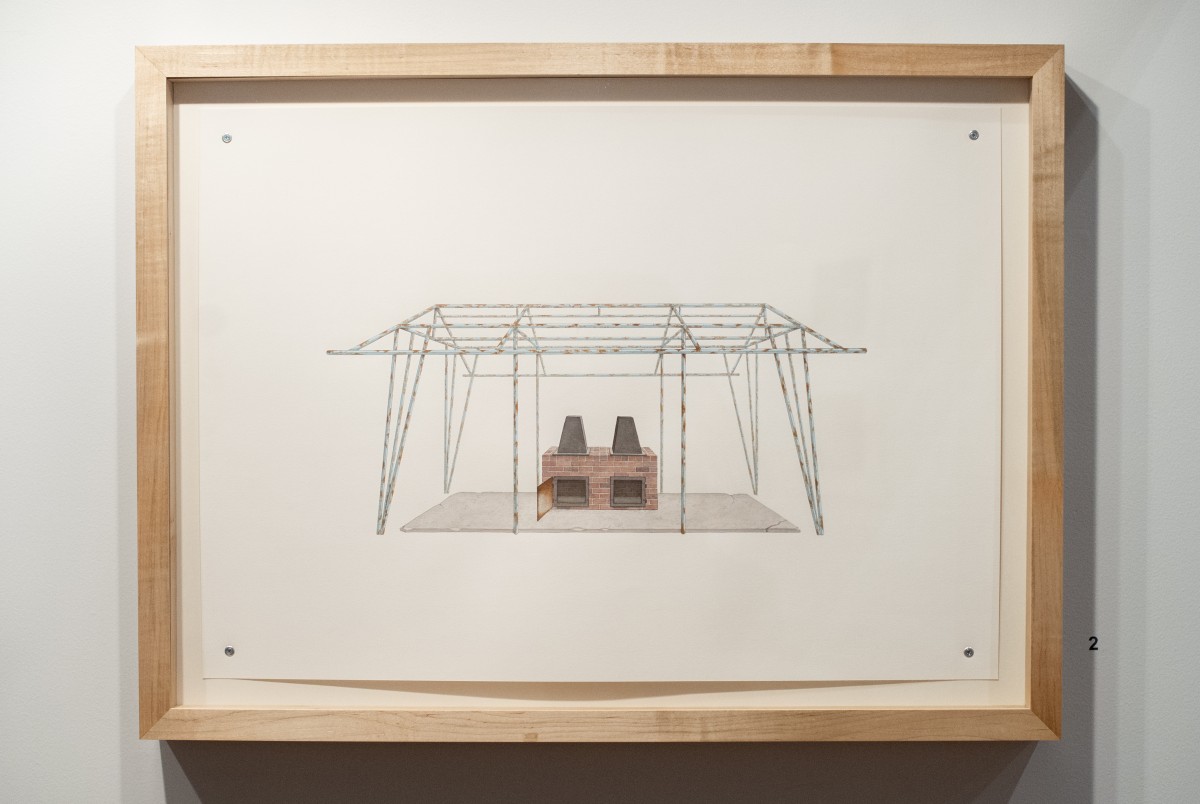

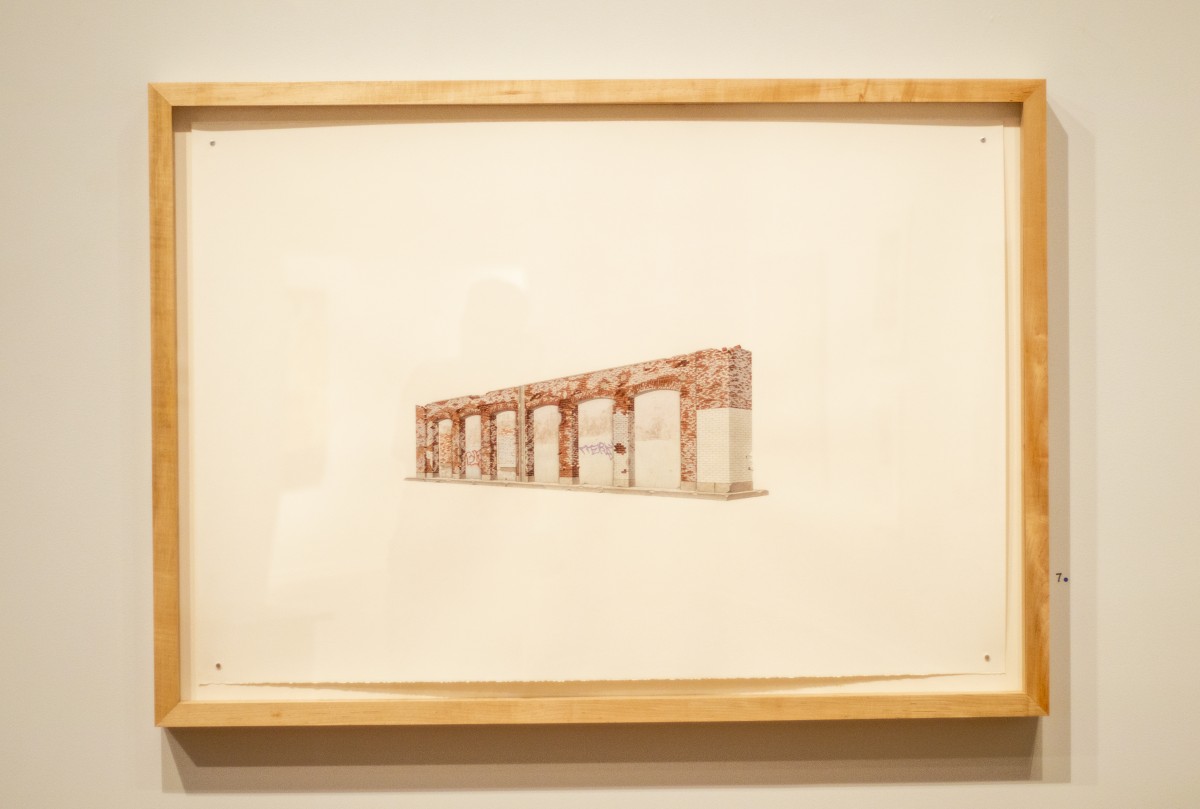

Working in a very different way is Nathan Heuer, whose extremely precise drawings make viewers question whether he is depicting real or imagined buildings. They have the same double-take effect of Claes Oldenburg’s proposed monuments that ranged from a toilet bowl float in River Thames, to a teddy bear in Central Park. Heuer’s “Next Year’s Remodel” features a series of brick buildings in a state of disrepair. Are we looking at urban decay or the beginning of new dwellings? Creative reuse is a recurring theme here. Heuer gives us a schematic rendering of a semi, but upon closer examination, there is an incongruous air conditioner on the roof. In fact, this piece records a repurposed rig retrofitted as an office/store in order to sell shrimp. The artist also follows in the footsteps of Giovanni Battista Piranesi, whose exquisite, mind-blowing architectural prints record both existing and imaginary structures.

Despite the differences in the work of these artists, they share an interest in an in-between space that exists somewhere between dream and quotidian, imagined and real. They all make the ordinary, extraordinary, in ways that evoke ideas of stranger than fiction, more real than real, and imagined fantasies. Their content, like their technique, has blown open the parameters of drawings with a freshness and excitement.

Vicky A. Clark is an independent curator, critic and teacher based in Pittsburgh. Throughout her 30 years in the Pittsburgh art scene, she has served as a curator for the Carnegie Museum of Art, the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, and curated “The Popular Salon for the People: Associate Artists at the Carnegie Museum of Art” exhibition.