NICK DANLAG – STAFF WRITER

Is there a difference between genetically modifying a fish or a rabbit to glow in the dark and breeding dogs for a preferred look?

As technologies that can change parts of the DNA of animals — and humans — expand, R. Alta Charo, the Warren P. Knowles Professor Emerita of Law and Bioethics at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, said humans will have to reckon with these kinds of questions.

Altering DNA has a lot of uses, from eliminating genetic diseases and making animals more resistant to changing climates. The application most in the spotlight, though, is potential changes to humans.

“Are we really upset about the technology, about the underlying thing it accomplishes, or simply about the fact that it’s now easier to do it and maybe more people will try?” Charo asked.

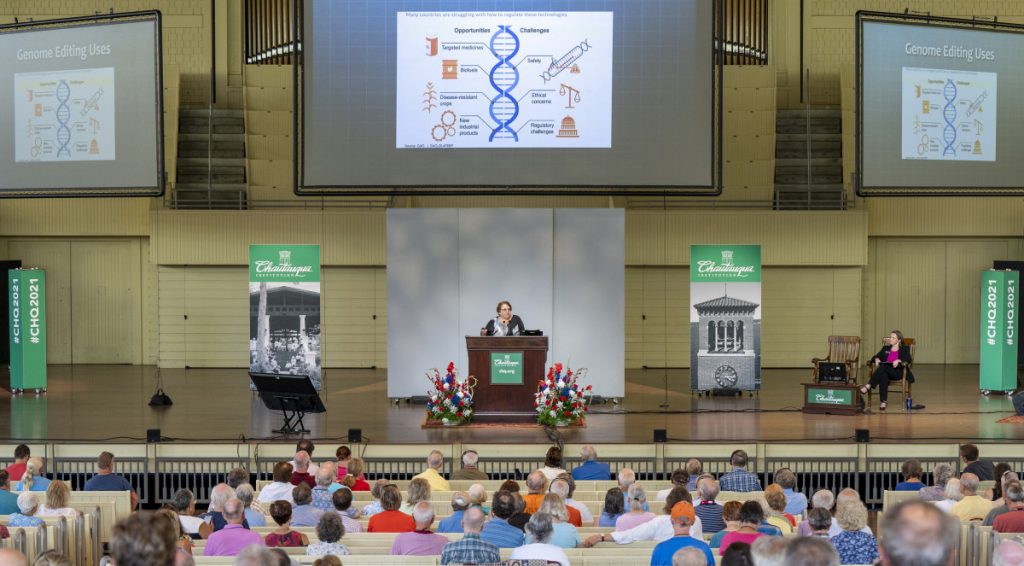

Charo, who spoke at 10:30 a.m. Wednesday, July 7 in the Amphitheater, is a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Medicine, and the inaugural David A. Hamburg Distinguished Fellow at the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

Wednesday morning, she explored society’s attitude toward genome editing, different current practices and how the advancing field has raised questions about what it even means to be human. Her lecture, titled “Now I Am Become Life, Creator of Worlds: The Era of Biotechnology,” was the third part of Chautauqua Lecture Series’ Week Two theme, “New Frontiers: Exploring Today’s Unknowns.”

Scientists weren’t always conscious of how far their work could expand. In the 19th century, many were simply enamored with the inventive power of science. But, as more and more catastrophic weapons were conceived and deployed in the 20th century, this captivation turned to terror.

J. Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, was eerily conscious of the power his work created. While testing the Manhattan Project during World War II, he witnessed the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, and quoted Hindu scripture: “Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

In the late 20th century, fear rose around the environmental impacts of genome editing. One experiment with genome editing attempted to protect strawberries from frost using a commercial product called Frostban; the woman spraying the strawberries wore a full hazmat suit.

“That image of having to wear a hazmat suit while spraying the field — something incredibly innocuous as genetic changes go — is probably what helped to lead to things like the fear of genetically engineered food that we now see,” Charo said.

Then public attitudes transformed again, this time with growing fear about reproduction. Instances of cloning, such as Dolly the sheep, Charo said, caused a media frenzy; some states even issued bans on cloning.

Charo gave two examples of more recent genome editing: the first was mammoths and another was tomatoes.

The first revolves around some scientists claiming reintroducing the mammoth would be beneficial to the ecosystem. Critics say that there is no way to measure the impact of reintroducing the species to an environment that has changed over thousands of years.

“It was really driven by this magical idea of bringing back extinct species,” Charo said. “There’s something really very romantic about that.”

The second revolves around hybrid tomatoes. The tomato was bred over the years in order to last longer and travel better, though this made it less flavorful. Now, there is an effort to create a tomato that is flavorful and able to grow in more places, so that the produce does not have to travel as far.

“If it was exactly the same, every base pair, every last one was identical between the one that we created, and the one that you picked off the vine originally — they’re literally identical in every possible chemical way — would it bother you that one of them has been engineered?” Charo asked.

Beyond extinct mammoths and everyday produce, the main focus within the field of DNA manipulation is combating genetic diseases, such as some forms of blindness and sickle cell.

Charo said the two forms of manipulation are treatments that change the genes of a single person, with the changes essentially lasting one lifetime; and changing the genes of embryos, with the changes able to be passed down.

One scientist focused on changing embryos in order to give children more immunity to HIV. His work caused controversy, Charo said, because of the touchy subject of the work; critics also said his work was completely unnecessary, considering that none of the mothers participating in the trial had HIV, and that medicine was already advancing to treat HIV.

“We have absolutely nothing near the level of basic science research that you need to even think you have a good way to predict how well this is going to work, and what level of risks you’re facing,” Charo said.

All of these are examples of how far humans have progressed, and Charo said humanity has more power than ever before. This change in humanity’s power has made people ask what being human even means and what it means to “play god.”

Charo’s final example was Mendel’s Dwarf, a novel about a geneticist with dwarfism. In one scene, he is looking at embryos in a dish and realizes he can choose which one to “bring to birth,” whether it be one with his genetic disease or not.

“He has this revelation that, for him, the deity actually is the one who just rolls the dice. The deity is the one who sets up a system,” Charo said. “He says, ‘If I choose, that is not being God, that is being human,’ a complete reversal of the way that phrase, playing God, is understood.”

Amy Gardner, vice president of advancement and campaign director, asked as part of the Q-and-A session international review boards exist for genome editing.

Charo said that she is on one of these boards, but enforcing and practicing policies mostly comes down to individual countries. An individual country’s policies around genome editing often come down to how they govern themselves, and the country’s primary religion. Majority Christian, Jewish or Muslim countries often hold different views on this topic.

In some countries, like the United States, everything is essentially allowed until the government says otherwise; in other countries, if the government doesn’t explicitly state that the practice is allowed, then it is not.

Gardner then asked what can be done to help societies adapt to the incredible rate of change of gene-editing technologies.

“Often the change does not happen across all segments of society. It doesn’t happen in a very big way,” Charo said. “There are technologies that people worry about because they think everyone is going to use it, but they won’t. So we don’t have to worry about (an) enormous societal impact.”

In terms of sperm donations, many thought, and still believe, that people would choose the donors who are taller and more conventionally attractive. One business used a model that almost guaranteed that the child would be tall, blonde and strong. Charo said this organization failed quickly because the business model counted on its customers prioritizing conventional beauty.

“You don’t get people doing it because they want to see if they can have a kid that’s going to be more athletic or not,” Charo said. “They do it because they don’t want a kid who is going to have cystic fibrosis and is going to be in the doctor’s office, day after day, month after month, trying to breathe.”