Howard Halle

guest critic

In French it’s known as “paysage,” in Italian, “paesaggio” and in German, “landschaft.” Whatever the language, landscape has played an integral part in the history of art, especially as a formally constituted category within the Western canon serving a whole host of aesthetic concerns from allegorical to non-objective.

As an artistic genre, landscape is believed to date back to sixth-century China, but as a manifestation of the natural world, it’s impressed itself on the collective imagination since the days of the hunter-gatherers, when it effectively meant living room, bedroom, dining room, bathroom, kitchen and larder. Even today, with all our capacity to insulate ourselves from — and destroy — the environment, we remain part of the landscape and it remains part of us. Moreover, we exist within a plethora of landscapes — political, social, cultural, media, etc. — that go beyond the term’s original meaning.

This last point figures into “Sense of Place,” curated by Chautauqua Visual Arts’ Erika Diamond, currently on view at the Strohl Art Center. Featuring five individual artists and one collaborative duo, the exhibition presents a series of unconventional takes that are less concerned with naturalistic depictions than they are with evoking certain resonances within a scene. The works vary in scale and medium, and while some play very loosely with the accepted norms of landscape, they all evince an interest in exploring the form as something other than physical.

For example: landscape’s relationship to memory, whether conditioned on individual experience, larger circumstances, or some combination thereof, serves as a noticeably potent theme for two of the offerings in show.

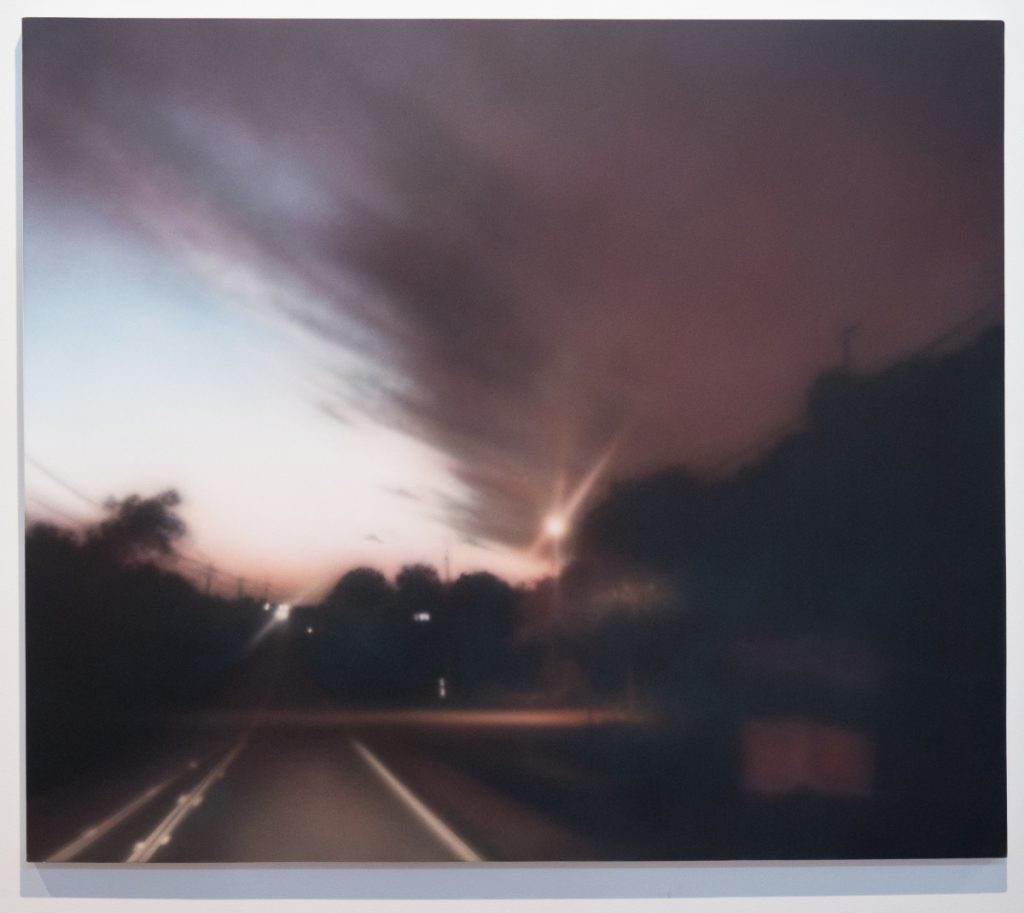

The first is Samantha Fields’ “Night Comes Early,” which recollects driving across Texas in a series of photo-realistic paintings describing roads shadowed by brooding clouds pregnant with tornadoes. Based on snapshots taken out of a car window, the results are slightly out of focus, giving them a distanced quality that shares noticeable affinities with the work of Gerhard Richter.

Fields’ compositions picture the latter of two separate sojourns she undertook through the Lone Star State that bookended the COVID lockdown. Fields found herself traveling through storms during both journeys and, in retrospect, one could easily construe her first trip as foreshadowing the crisis to come. Her second excursion, however — the one she committed to paint — is intended to symbolize liberation, offering “a visual feast after a year of seeing nothing but our own backyard,” as she puts it.

Similarly, Lien Truong and Hong-An Truong’s “The Sky is Not Sacred,” also relates landscape to memory, though in its case, one contextualized by a historical event: The Vietnam War. Comprising a painted triptych and single-channel video, the piece delves into a little-known aerial campaign conducted by the CIA, codenamed Operation Popeye, which sought to weaponize the weather against the Viet Cong. The idea was to increase rainfall above Communist supply lines in parts of Laos and North Vietnam, making them impassable by seeding clouds with agents such as lead and silver iodide. The endeavor proved useless in the long run and was discontinued, but here, it serves as a jumping off point for a meditation on how warfare reshapes terrain, creating its own kind of landscape.

Lien Truong’s three-panel oil on paper rendering tackles Operation Popeye directly, re-imagining de-classified diagrams linked to it as a roiling red mushroom cloud against a matching sky marked with the tiny silhouettes of two aircraft. Hong-An Truong’s video, meanwhile, features wing-camera footage of a bombing run on a jungle below, accompanied by a voiceover reading a treatise on landscape by the 19th-century British painter John Constable, who waxes poetically on his love of the sky, among other things.

Indeed, evoking the heavens factors into “Night Comes Early” as well as “The Sky is Not Sacred,” though the latter’s nod to Constable brings up another issue tying them together, namely, the Romantic Sublime. So called for its embrace by the artists of the Romanticism movement, of which Constable was one, the notion was first articulated in 1757 by Edmund Burke in his “Philosophical Enquiry,” which stipulated that nature held a unique ability to elicit terror and awe in the mind of the beholder, reactions evoked in the stories that both projects tell.

Burke’s theory of the Sublime also figures into the contributions of the remaining artists in the show, though their respective methods are less reliant on narrative than they are on an exploration of materials or techniques.

Of this group, the work of María Fernanda Barrero is the most representational, and even depicts the sky, though far less forebodingly than either “Night Comes Early” or “The Sky is Not Sacred.” Tonally, Barrero’s pieces are exactly the opposite, with serene vistas in shades of cerulean interrupted by fluffy contours in white. Three of these are framed as views through the window of an airliner in flight; small yet seemingly infinite, they distill a sense of preternatural calm in compact form.

What distinguishes Barrero’s images, though, is that she made them by applying waxed thread to panels of wood or sheets of paper—a combination of textile art and collage creating a raised surface that lends a topographical aspect to the result. The careful placement of one strand after the next also reinforces the contemplative quality of Barrero’s approach, especially in several pieces — like one from 2018 titled “Amanecer 01 (Dawn 01)” — that resolve into nearly pure, geometric abstraction.

As it happens, “Amanecer” chimes exceptionally well with Mika Obayashi’s “Gospel of Three Dimensions,” the largest of her two mixed-media sculptures included in the show. A large , rectangular installation — measuring 7 feet by 7 feet by 11 feet — “Gospel” is hung from above by cotton cords that suspend layers of Abaca paper dyed with indigo. Each sheet has irregular edges and appears to undulate when seen from the side. Together, they resemble waves, an impression reinforced by a color scheme that goes from deep blue to white as the eye travels towards the ceiling. You might call “Gospel” a seascape, except that a C-shaped channel running up one face of the structure lets you enter a space that provides a close-up look of “Gospel’s” interior, making it seem as if you’ve entered a shaft cut through a geological stratum.

Finally, Liz Nielsen offers several images that rely on a photographic format as old as the medium itself: photograms. This camera-less process entails the placement of objects on photo-sensitized paper or film that leave a ghostly afterimage once they’re exposed to light. Here, Nielsen used handmade negatives and repeated exposures to create richly chromatic effects. A couple of pictures feature objects that appear to be stones smoothed by the rushing waters of a river; elsewhere, sinuous cut-out shapes conjure mountains and trees. Taken together, Nielsen’s work reminds us how essential light is in affecting our impressions of landscape — as do all the intangible qualities touched upon by “Sense of Place.”

Former Editor-At-Large and Chief Art Critic at Time Out New York, Howard Halle writes regular exhibition reviews, including for Art & Object.