Julia Weber

Staff writer

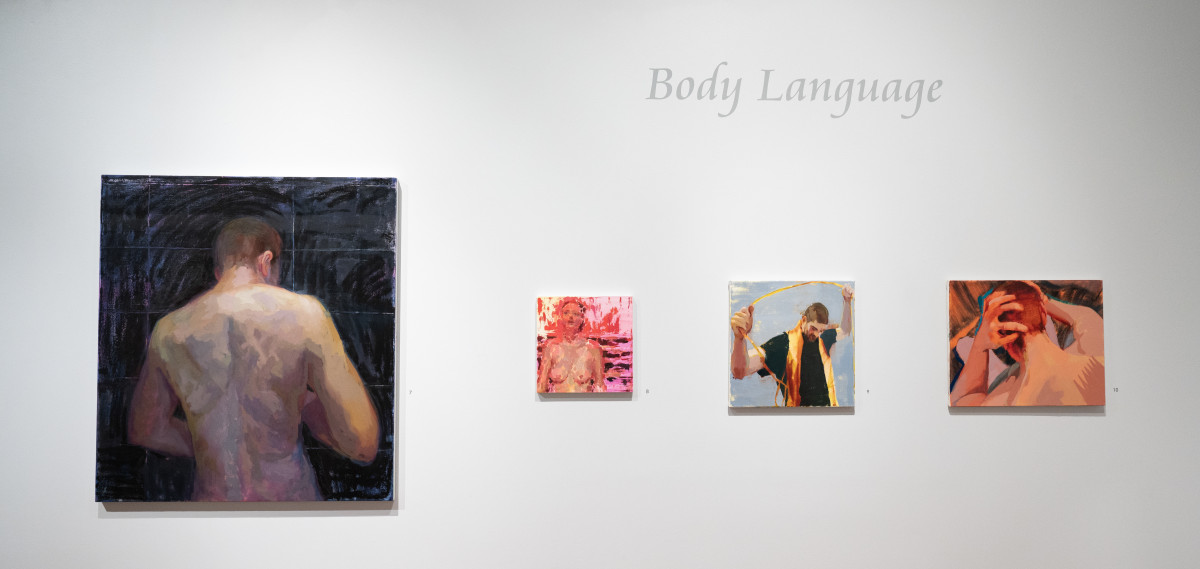

Chautauqua Visual Arts aims to approach one of the most intimate forms of communication, body language, with an exhibition bearing that name.

“Body Language,” curated by the John and Susan Turben Director of CVA Galleries Judy Barie, is on view until Sunday in Strohl Art Center.

“Art is another form of a language,” said Kensuke Yamada, whose large sculptures are centered in the gallery.

Yamada’s pieces are childlike and imaginative, exploring mindfulness and connection between artist, art and viewer. In his artistic description, he writes: “I hope for my work to fill the space between two seemingly distant things, to provide a connection and thus create the story of you and me.”

Instead of finding differences, Yamada said he looks for similarities.

“I always look for what’s common between us,” he said. “I try to find why we are similar, especially (the) emotional parts.”

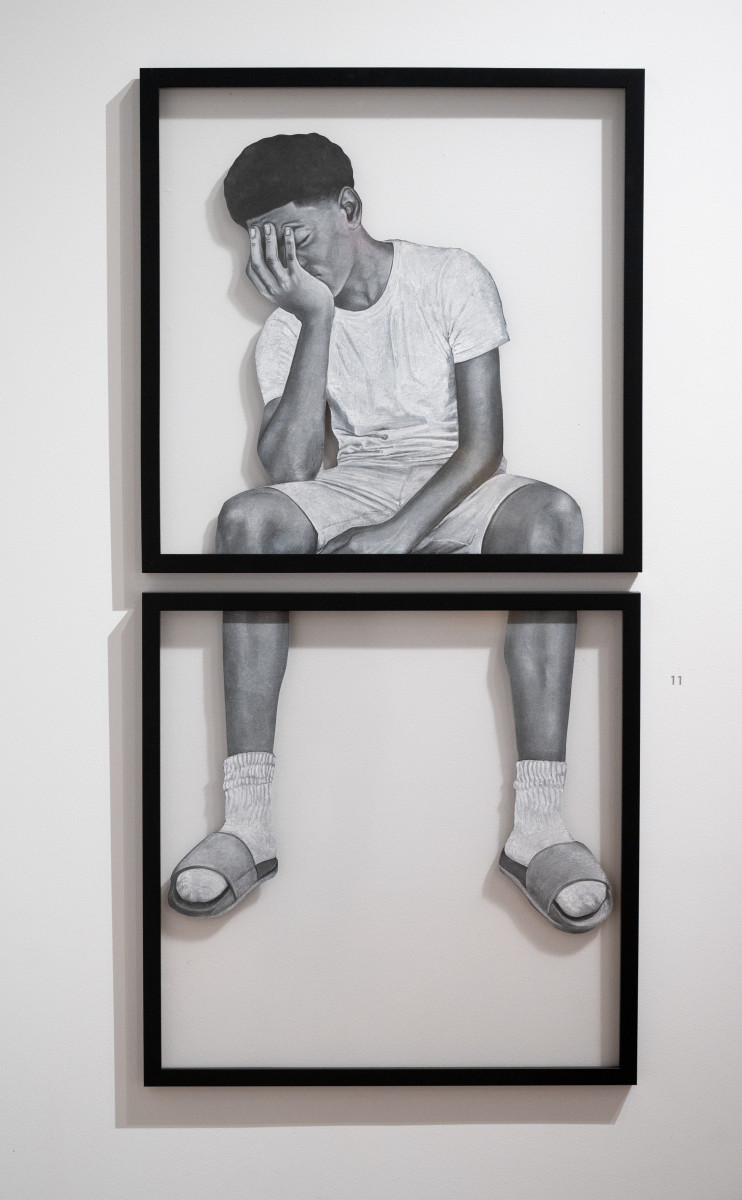

Spanning the walls of the gallery, Chris Friday’s large-scale hyperrealistic portraits show Black people at rest and enjoying privacy. For Friday, it’s important to portray Black people engaged in vulnerability and restfulness.

“My work explores themes of rest, privacy, and supplementing the archive as a way of advocating and claiming space for Black bodies that are historically excluded from it,” Friday’s artistic description states. “ … I give my subjects the rest and privacy they are entitled to, even while on display; reflecting the longing to achieve this for my community, my family and myself in everyday life. ”

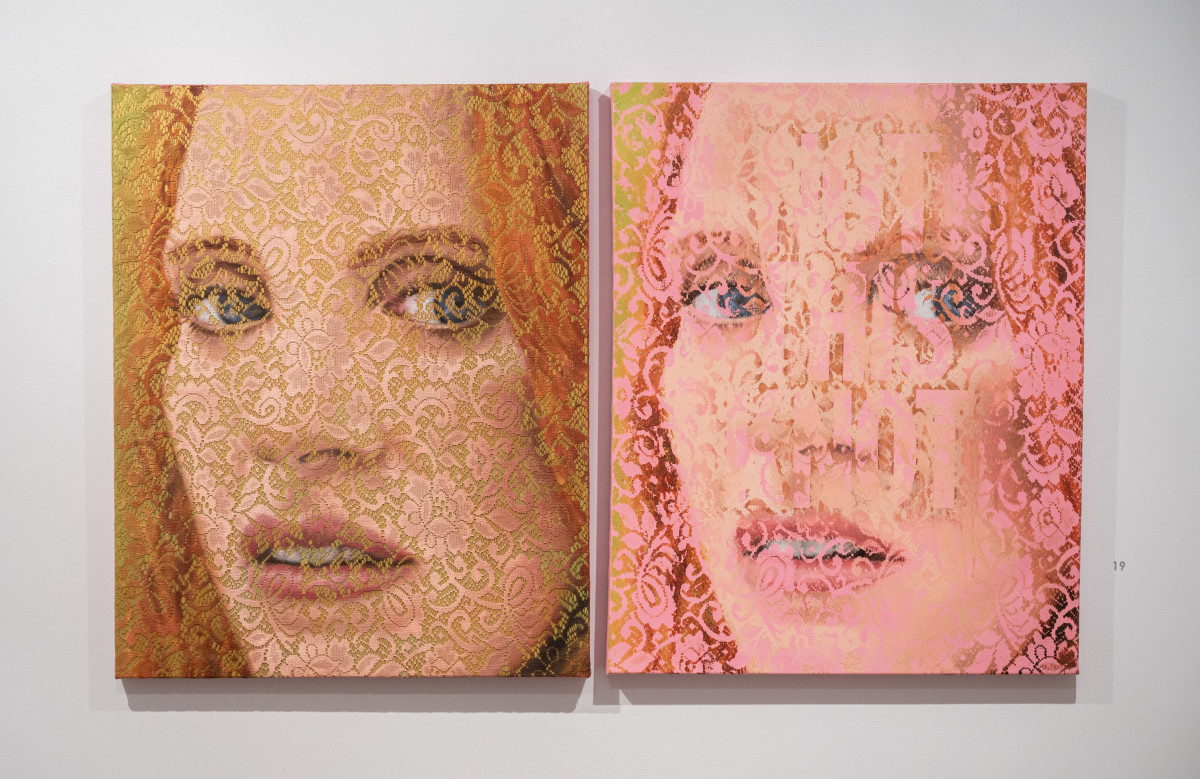

Elizabeth Coffey’s interspersed paintings explore femininity and gender expectations that are associated with being a woman. She uses textiles, specifically lace, in her paintings to comment on how textiles have historically been associated with femininity.

“It’s really important to me to explore the tension between the seen and the unseen, and what we choose to reveal to people and what we choose to conceal,” she said.

Coffey explained that lace, to her, often serves as a veil. The textile physically conceals and obstructs, but on another level, the material is historically associated with femininity, and Coffey is interested in understanding the relationship between the two.

“It is representative of the domestic art and the ways that women traditionally were able to express their creative desires related to the home,” she said.

Oil portraits by Rachel Rickert are interspersed through the gallery, portraying individuals in their most vulnerable moments. Her paintings aim to explore her inner world and all its anxiety, attachment and intimacy, she said.

For Rickert, it’s a practice in examining and untangling her feelings.

“I started to try to find visual equivalents to that by pretending to be a voyeur on myself in a lot of ways – catching myself in the mirror and seeing myself during certain moments, and seeing what is the physical representation of being in my own head,” she said.

Her paintings depict herself or her partner in moments of daily life, such as in showers, saunas and glimpses in the mirror.

“I love the term ‘body language’ because that’s exactly what I’m trying to figure out. What is the physical representation for these psychological sensations?” Rickert said. “What does the body do when you are feeling vulnerable? What does the body do when you’re feeling anxious? What is your body language when you are receded within your own thoughts?”

Francis Crisofio’s photographs are “part documentation and part interpretation of a collaborative, after-school arts curriculum based on self-portraiture,” according to Crisofio’s artistic description.

The series combines new portraits of subjects with other media like drawings and recycled photographs. The series aims to unpack the relationship between self and “other” and understand race, class and gender dynamics, according to the description.

Beverly Mayeri’s sculptural ceramics explore our innermost emotions and feelings. Her pieces, sometimes witty and humorous, take sculptural ceramics and ask viewers to consider the different ideas she might be offering with her pieces.

She hopes her pieces will intrigue viewers and make them think about the commentary she’s offering.

“I like to think that a viewer would either see the humor in some of them or be intrigued by what’s happening in the piece,” Mayeri said, “then go closer and take a closer look and think about ‘What is going on there? What is this about?’”