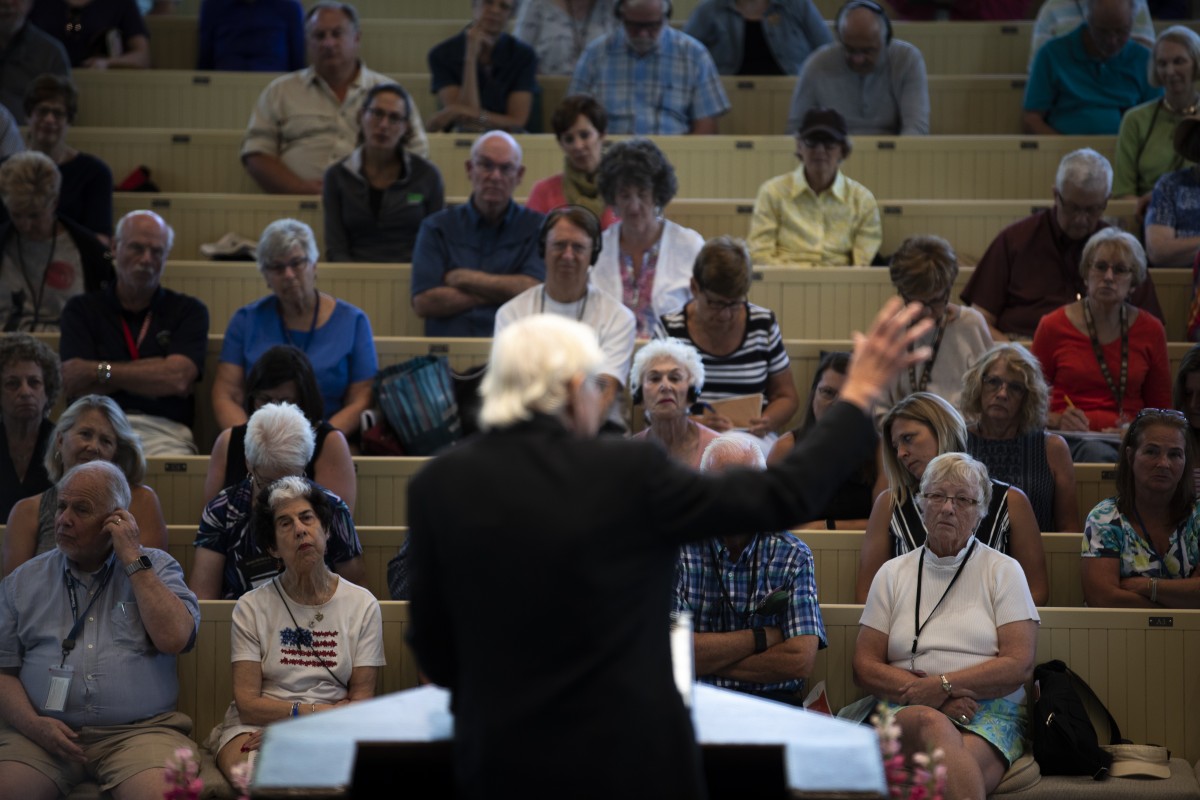

During his lecture, psychologist Peter Gray promised it would be “the least happy talk about play you’ve ever heard” — and he delivered.

Gray spoke to the inherent need for, and the decline of, play among children at the 10:45 a.m. morning lecture Wednesday, July 11, in the Amphitheater, continuing Week Three’s theme, “The Art of Play.”

“The absence of play is depression,” Gray said, a point he argued extensively in his book, Free to Learn: Why Unleashing the Instinct to Play Will Make Our Children Happier, More Self-Reliant and Better Students for Life.

As an evolutionary psychologist by trade and a research professor of psychology at Boston College, Gray has focused throughout his career on the “curiosity, playfulness, sociability and willfulness” of children at a biological and social level.

Natural selection shapes the play of animals and humans alike, Gray said. Predatory animals play by chasing and pouncing to learn to hunt; preyed-upon animals play by running and dodging to learn to avoid being hunted.

“From a biological perspective … play is nature’s way of ensuring that young mammals practice the kinds of skills that they need to develop to live and thrive as their species in the environment in which they are growing up,” he said.

However, running, chasing, pouncing and dodging may not be “play” for Gray. He has a four-point criteria for what constitutes play: play is self-directed and self-chosen; play is intrinsically motivated; play is guided by rules; and play includes an imaginary element.

For play to be self-chosen, children cannot be directed to play by teachers, parents or superiors. Although games in school can be instructive and educational, it is not “play,” he said.

“(Play is) how (children) learn to make choices,” he said. “It’s how they learn to direct their own activities, and when we take that away from children by creating the activity for them, directing the activity for them, we are taking away the opportunity for them to learn how to create and direct their own activities, solve their own problems.”

The lack of these learned abilities can translate into adulthood. Children who play in risky ways and try new, sometimes dangerous, forms of play are better equipped to handle the challenges adult life might throw at them, Gray said.

“All of us are going to face real risks in our lives, and it’s a good idea to practice with risks in relativity controlled conditions of play, so that the first time you are in true danger … you can keep your head together and not have a panic attack,” he said. “So that little girl that climbs the tree too high, what is she doing? She is developing courage.”

For play to be intrinsically motivated, Gray said it must be self-chosen and must “discover and follow passions.” While play is an act of passion, it must also be guided by rules — rules established, chosen and accepted by children. Finally, play must have an imaginary element.

Imagination is the only thing that separates humans from animals, Gray said.

“In some sense, in play you are always stepping outside of the real world into a fantasy land, into an imaginary world,” he said. “Even in a game like chess, it is an imaginary world where bishops only move on the diagonal — unlike the real world, where they can go wherever they want.”

Despite the abundance of opportunities for play, over the last six decades Gray has seen a nationwide loss of play — an epidemic he called a “national tragedy.”

“There has been a continuous, gradual, but overall huge decline in children’s freedom and opportunity to play,” he said. “There is no comparison between the freedom that children had in the 1950s and the lack of freedom that children have today.”

Gray reflected on his own childhood in the 1950s:

He was able to play outside, without supervision, throughout the day with other children in the neighborhood; he described having two hours of recess a day and not having homework in elementary school.

“We never carried books or worksheets back home. We did in school what school was, at home we played with our families,” he said. “Our parents were not supposed to be assistant teachers. They were not there monitoring your homework; for the most part they didn’t know how we were doing in school. They didn’t want to know, and we didn’t want them to know.”

Gray said he had two educations growing up: traditional schooling and a “hunter- gatherer” education (the hunter-gatherer education was more valuable). In “hunter-gatherer” cultures, children are encouraged to play, especially at critical ages when most western cultures are pushing the importance of school on their young.

“Today, if you go out in almost every neighborhood in America, if you find children outdoors at all, they’re likely to be on some kind of a manicured field, wearing uniforms, being directed by adults — that’s not play,” he said, stressing that social lessons taught by unorganized, free play are more important than the technique of a sport.

Gary attributes the decline of play to three reasons: the spread of fear, increased pressure on children and a “schoolish” cultural outlook.

According to Gray, “the world actually is not more dangerous than it was decades ago,” and crime rates are steadily declining. But people are still fearful of traffic accidents, and yet in places with minimal traffic, children are still denied play. People are fearful of child predators, yet they fail to acknowledge the rarity of the crime, Gray said.

“We are so afraid that we deprive our children of what they most need — the opportunity to get away from us and play with other kids,” he said.

Students have been reduced to numbers and admissions — parents think about college applications while the child is still in the womb, Gray joked. School and extracurricular activities absorb children’s time because people fear that without structure, children won’t succeed.

“We have in our society, by and large, what I refer to as a ‘schoolish’ view of child development,” Gray said. “That’s the view that children develop best when directed by adults, and that children’s own activities are a waste of time. … We want to control them.”

And the desire to control children has dire consequences. In the last 60 years, Gray said rates of major depressive disorder have increased eightfold; anxiety disorder rates have risen between five and eightfold.

“Should we be surprised by that?” he said. “We have put children into what I think even we adults would regard for us as anxiety-provoking divides where you’re constantly being monitored, you’re constantly being evaluated, you’re constantly being judged, you’re constantly being compared with your peers.”

Gray asked: What is society doing to this next generation that is making them the most stressed demographic in the country?

“I’m calling it ‘play deficit disorder,’ ” he said. “And the only cure is play.”

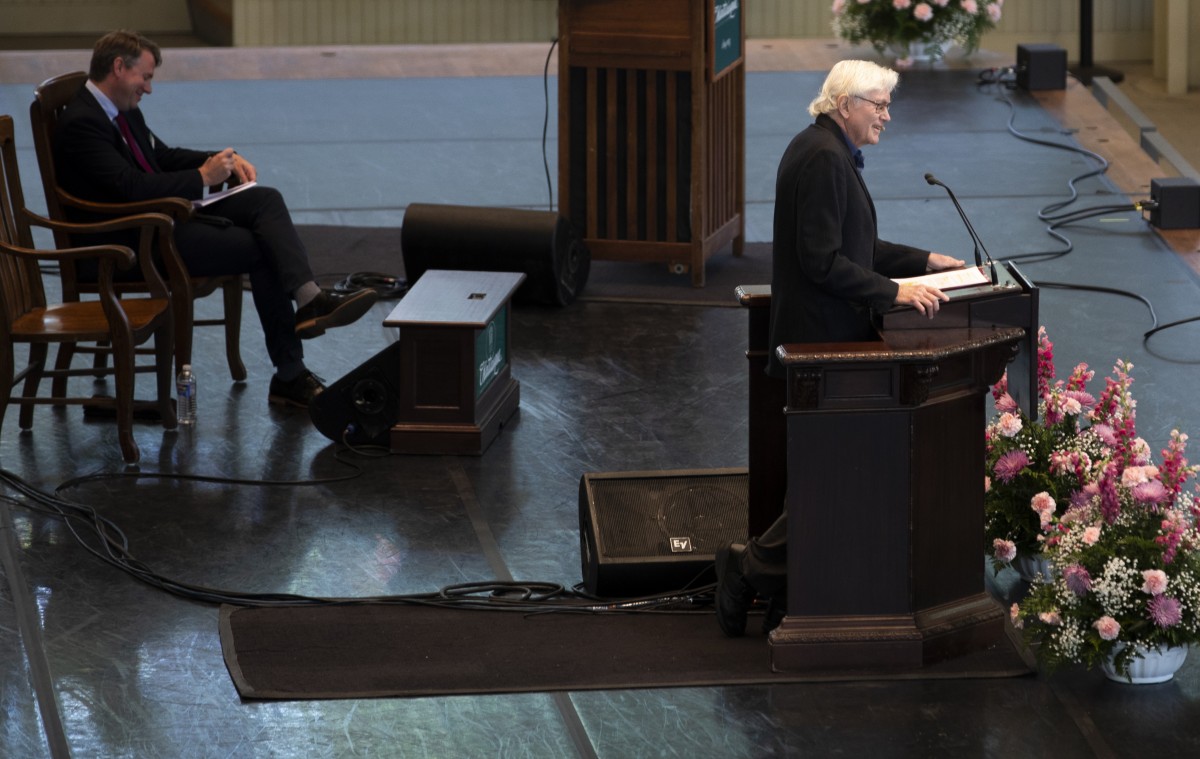

After the conclusion of Gray’s lecture, Dave Griffith, vice president and Emily and Richard Smucker Chair for Education, opened the Q-and-A. He asked if there was a correlation between the decline in play and the rise in obsession with higher education.

“If we were seriously concerned about education, you would think about what are the things really, really important in our culture,” Gray said. “And I think what we would conclude is that things that are really, really important to learn, like being creative, like being self-directed, like understanding who you are, like being able to control your emotions, … none of these things are part of our education. These are things you learn in play.”

Griffith then turned to the audience for questions; one attendee asked if Gray’s research revealed gender difference in play.

Gray said that through ages 8 to 11, children self-segregate their play — boys playing with boys and girls playing with girls, something absent in younger children. However, Gary believes in the importance of letting children play with whoever they want.

To close, an audience member asked if video games were a form of play. Gray referred back to his four characteristics of play. He argued that video games fit each of those criteria and therefore are a form of play. However, he did stress giving children time outside as well.

“We have created a world where it’s not much fun for (children) to go outdoors,” he said. “There’s not much opportunity for them to find and play with other kids. Kids more than anything else want to play with other kids … and if there are other kids playing outdoors, they will go out and play, and they will balance that with their video games. … My feeling is that we just have to trust kids.”